Ahmed Mohamed: Why some Muslims don't want the teenager's blackness to be ignored

What does being 'brown' mean in America?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

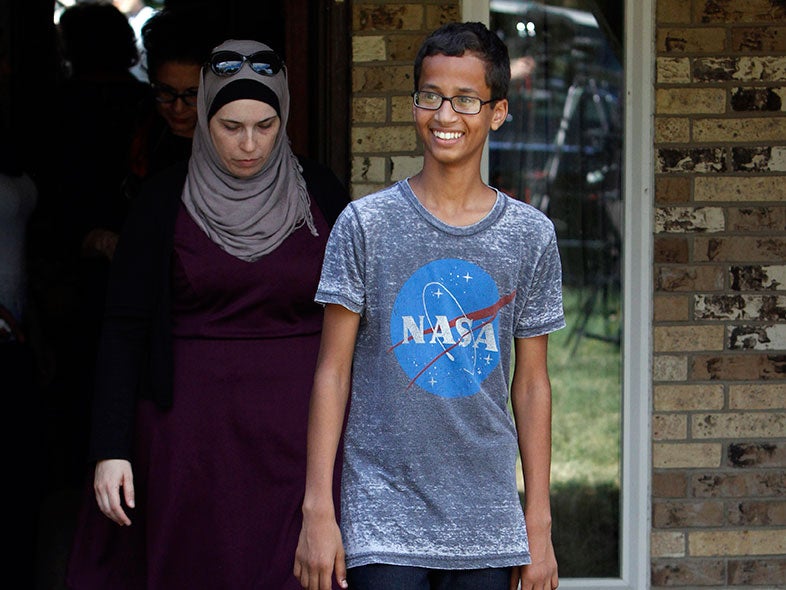

Your support makes all the difference.Ahmed Mohamed is now a 14-year-old with a national following and a long list of powerful people on his calling card.

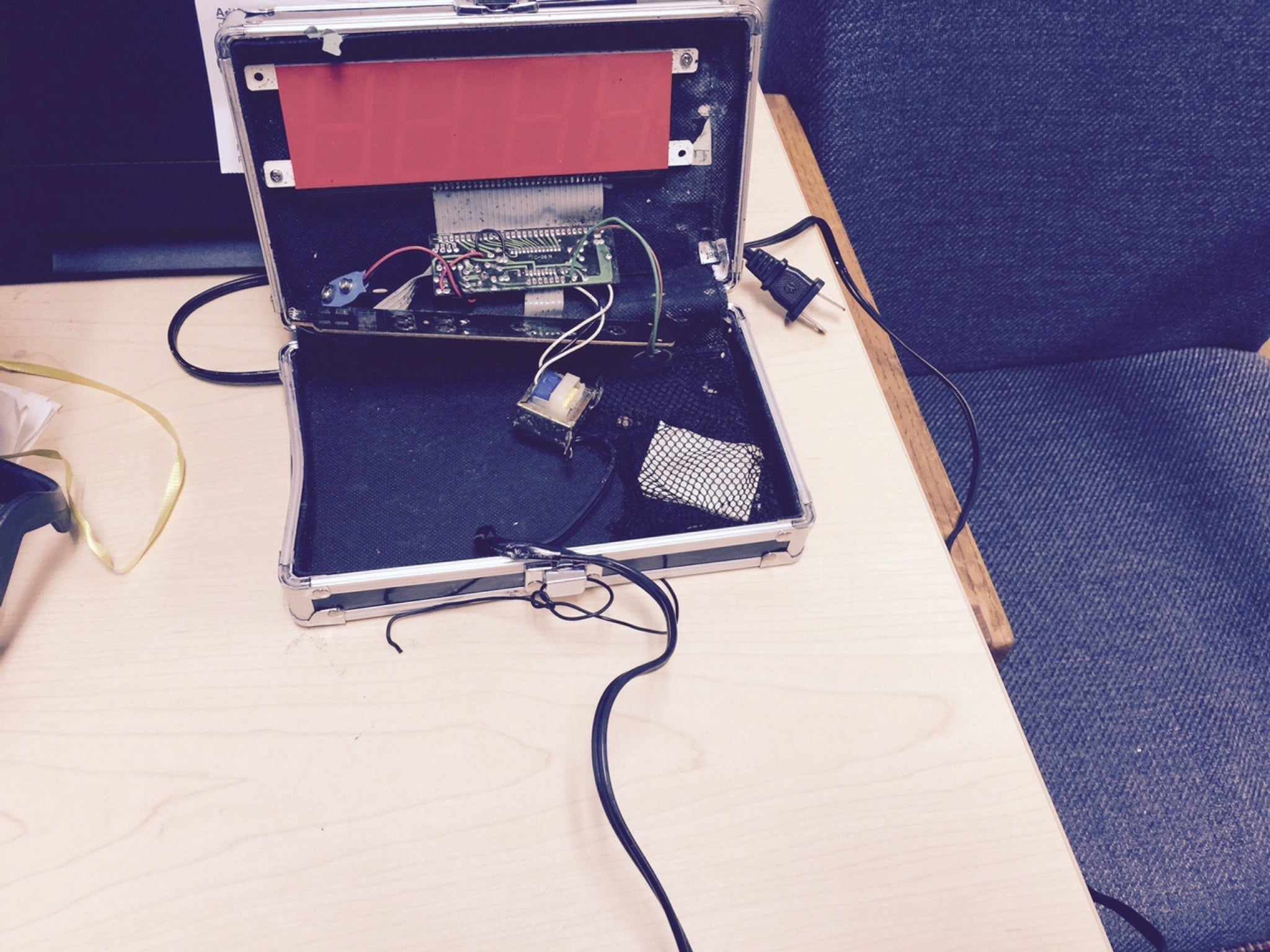

After he was arrested for bringing a homemade clock to school to impress his teachers, the teenager has become symbolic of the worst skeletons in America's closet: growing hysteria and over-criminalization in American schools, Islamophobia and racism.

As the news of Mohamed's plight spread, some of the earliest accounts associated the teen, who is of Sudanese descent, with the word "brown," a fuzzy bit of racial jargon that typically refers to non-black people of South Asian or sometimes Latin American descent.

And others openly wondered how the world might have reacted to Mohamed's story if he had been black.

More on Ahmed Mohamed:

Don't stand with Ahmed if you're not prepared to support all marginalised Muslim kids

Texas police knew Ahmed Mohamed didn't have a bomb

Ahmed Mohamed's parents handed out pizza to reporters

But Mohamed's racial identity is as complex as the country of his descent. The African nation of Sudan is predominantly Muslim and is comprised of some 600 ethnicities. Arabs and indigenous Africans have intermarried and mixed there for centuries and most speak Arabic.

To wit, the phrase given to the region now inhabited by Islamic people in Africa, which includes modern-day Sudan, is "Bilad al-Sudan" and it means literally "the land of negroes" or "the land of blacks."

Further complicating the situation is the fact that high-profile praise came from such figures as Indian American comedian Aziz Ansari, who compared his own experience to Mohamed's.

"#IStandWithAhmed cause I was once a brown kid in the south too,” Ansari wrote on Twitter.

Anil Dash, a tech entrepreneur of Indian descent, who was among the first to publicize Mohamed's story to his more than half-a-million followers, told The Washington Post that he was struck by the teen's story simply because he saw himself in the "skinny brown kid."

"My identification was literally: I physically looked similar. I had the same glasses and I was skinny. It was on a purely physical level," Dash acknowledged.

Dash reached out to Mohamed's family and counseled them on how to cope with the impending deluge of media attention. He cautioned them to change their passwords, create a Twitter account. Dash was the first to tweet out the now-infamous photo of Mohamed handcuffed in his faded NASA T-shirt.

But Dash said that he actually doesn't know whether Mohamed or his family identify as black. But they have been clear from the beginning that their religious identity is an important — if not the most important — factor in the 14-year-old's treatment by the school and police.

Online, another discussion brewed. Did the repetitious association of Mohamed with the term "brown" erase his blackness and render it irrelevant to his experience as an American Muslim of African descent?

"The issue of race in America, especially when it comes to Sudanese Americans, is complex," added Dawud Walid, executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations in Michigan, who also weighed in on the debate on Twitter. "There’s a misunderstanding among many people about what Arabness means. Arabness and blackness are not mutually exclusive, just like being Latino and black are not mutually exclusive.

"That’s a part of his identity. Someone like Ahmed can be equally American, Muslim, Arab and black," he noted.

But what does "brown" even mean? The answer depends on who you ask.

According to Dash, it is a "loving inside version of people’s color," that is in some way pan-ethnic in nature. It applies unevenly to Asian, North African, Middle Eastern and Hispanic people.

But he recognizes that in America, it is rarely used to describe black people.

"Most of my black friends that I talk to about my identify say 'brown is not me,' which I totally get," Dash said. "Being black is a unique thing in this country."

"It's not simple, but definitely brownness is not conferred to Sub-Saharan Africans," Walid said. "That term, brown, is predominantly used for people who are non-white, whose heritage comes from Latin America or South Asia and perhaps North Africa. But Sub-Saharan Africans period are not referred to as 'brown.'

"Most Sudanese Americans who are walking the streets in Western-style clothing are indistinguishable from African Americans," he added.

If the debate has smacked of racial policing, as some have suggested, it shouldn't, according to Hind Makki, a Sudanese American who has also pushed for people to be more "precise" when referring to Mohamed and his family.

"When people discuss Islamophobia, Muslims are racialized into this amorphous 'brown,'" Makki noted. "If you’re from Africa, [being black] is a huge part of Muslim history. Even in the U.S. overall, a third of American Muslims are of African descent.

"To erase that or to say that it's really not important — that Muslims should be fine with being described as a generic brown — I don't think that's right," she added.

While first-generation immigrants like Makki's parents often resisted being placed in a racial box, their children — like Ahmed — face the reality that in America, Sudanese Americans often view themselves as indistinguishable from black Americans, Makki said.

It is part of a broader story of Muslim and Arab identity in America. For years, people of Middle Eastern and North African descent have protested being forced to check "white" on census forms that tacitly ignored the ethnic diversity within Arabic-speaking countries like Sudan that were — for political and expediency reasons — lumped in with Caucasians. The Census Bureau announced that it would consider adding a category Middle Eastern/North African to better account for the growing number of people of Arab descent who now live in America.

Among those people, Afro-Arabs have a distinct Muslim story Makki said.

"Every single Sudanese American person I know, from every Sudanese ethnic background that I know, identifies as black in America," she added. "The African American and the black Muslim story in the U.S. is part of the Muslim story and you can’t erase it."

Copyright Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments