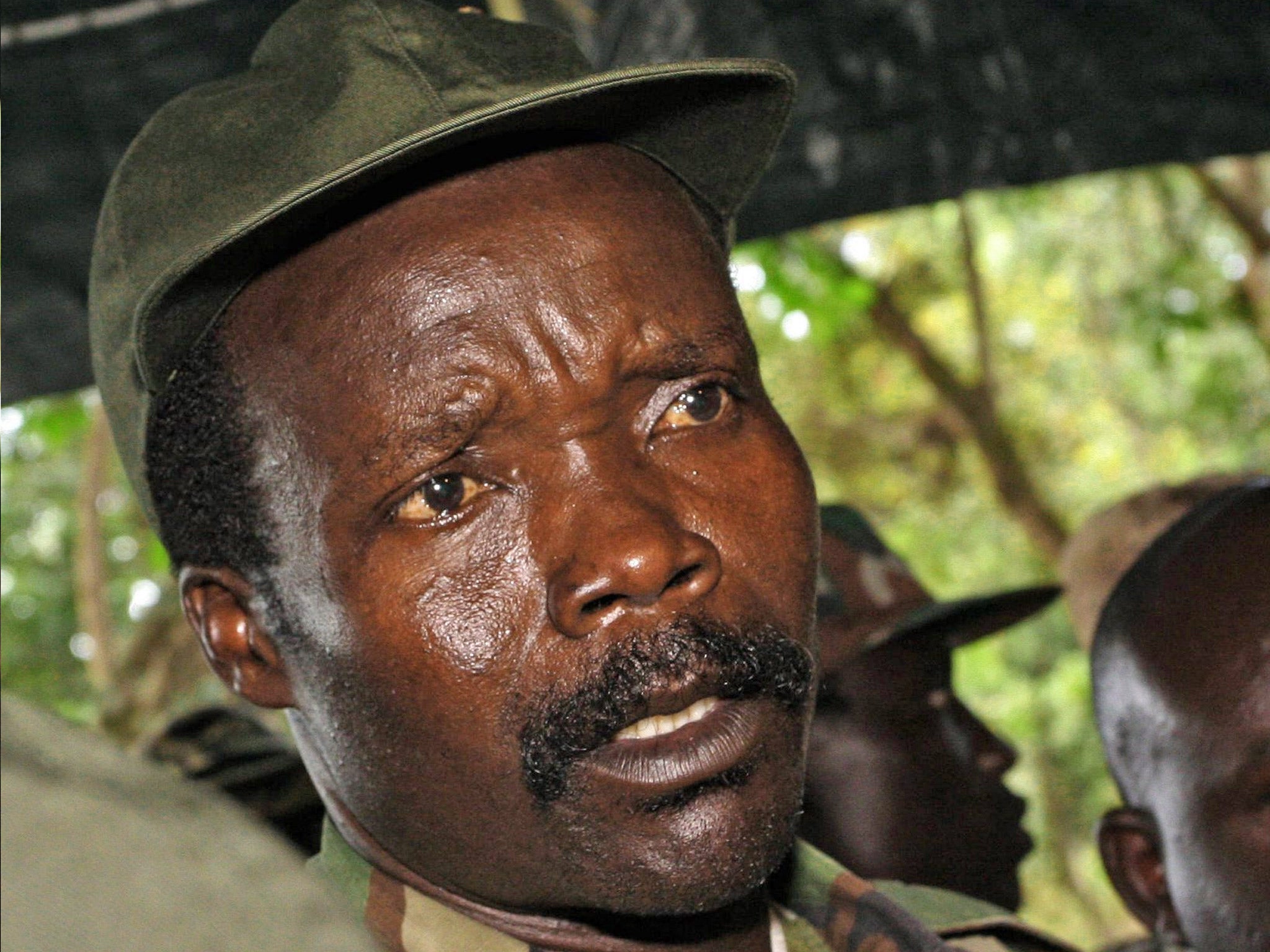

The hunt for Joseph Kony: US steps up search for Ugandan warlord

US Special Forces are helping African troops in their hunt for the messianic rebel leader - and the pieces are finally coming together

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For 15 hours, a team of US Special Forces soldiers shepherded four dozen South Sudanese commandos through an unremitting night time rainstorm, plunging into elephant grass so tall and thick they could not gaze beyond the reach of their arms. They heard the telltale cry of a panther and the ripples of crocodiles lurking in the bogs.

Their destination was a crude encampment used by the Lord’s Resistance Army, a band of rebels led by the messianic warlord Joseph Kony, who has spent years kidnapping and killing villagers – and eluding his pursuers – across a wide area of central Africa. By the time the troops reached the camp, as beams of morning light pierced the treetop canopy, the rebels had absconded again. The soldiers gave chase for a day, summoning tracking dogs and an infrared-equipped drone, but their quarry melted into the dense Congolese jungle.

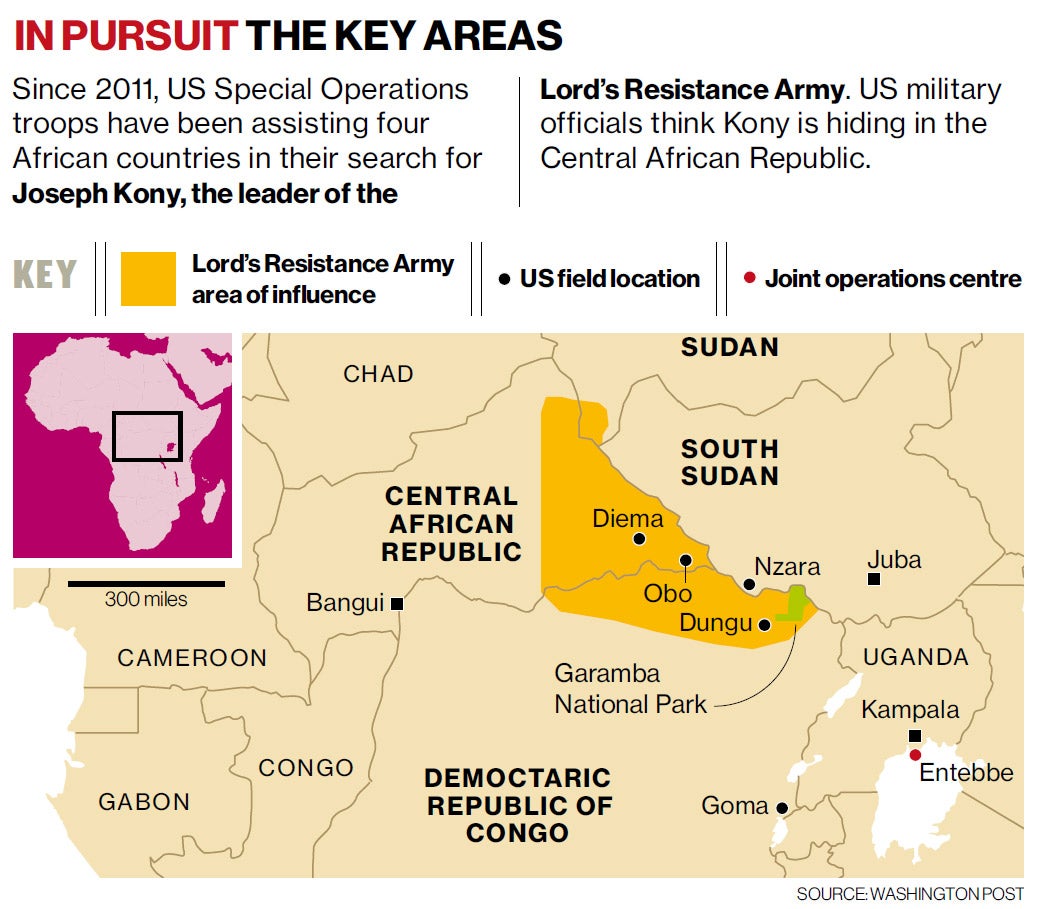

The September raid captured, almost perfectly, the state of the under-the-radar US campaign to help hunt down Kony and his top lieutenants. After two years advising and assisting local troops in four African nations, American forces have significantly expanded their activities – but Kony is still not in handcuffs or a casket.

The assault on the camp last month was the first time US Special Operations advisers had provided in-the-field support to African forces searching for Kony’s rebels in Congo. To the north, in the lawless Central African Republic, where Kony is thought to be hiding, US soldiers have intensified support for Ugandan troops seeking his redoubt. The Americans also have increased training of South Sudanese and Congolese units participating in the hunt.

Senior US officials say the Pentagon had asked the White House for permission to further widen the mission by temporarily basing sophisticated Air Force CV-22 Osprey aircraft in Uganda, allowing American and African troops to move across a broader area and more quickly assault Kony’s camps. Personnel to operate the Ospreys, which can land like helicopters but fly like planes, would nearly double the number of US troops in Uganda.

“We’re at a new stage in this mission,” said Colonel Kevin Leahy, who commands the 100 Special Operations troops pursuing the Lord’s Resistance Army. “All of the pieces are coming together, and we’re pushing on all fronts.”

Kony is a tenacious adversary. His fighters, some of whom were conscripted as children, are divided among several semi-autonomous cells spread across an area the size of Texas. They remain peripatetic, bedding down in camps nestled deep in the jungle, under foliage that shields them from cameras on American drones and satellites. They eschew two-way radios – their signals can be tracked – and attacks on villages large enough to quickly summon help.

“This isn’t searching for a needle in a haystack,” Leahy said. “It’s searching for a needle in 20 haystacks.”

Under rules set by the Obama White House, the Special Operations troops involved in the pursuit are not allowed to conduct unilateral missions – their role is limited to training and advising African forces. If a battle ensues, the Americans are to pull back; their rules permit shooting only in self defense.

In many ways, the military effort is regarded by commanders as a model for addressing pockets of instability around the world – facilitating local forces to lead the fight instead of Americans charging in as they did in Iraq and Afghanistan. “The Americans are providing the resources we lack,” said Ugandan Brigadier Samuel Kavuma, who commands Ugandan, Congolese and South Sudanese forces involved in the search.

The hunt is among the most unusual military operations since the 9/11 terror attacks. Kony is not an Islamist extremist or a narcotics smuggler. He poses no jeopardy to the US, nor is he an existential risk to any African nation. Although he once held sway over a substantial portion of central Africa, the Ugandan military campaign to neutralise him, which began more than a decade before US troops arrived, has shooed him from populated areas. His ranks decimated, he is thought to command fewer than 250 fighters.

Even so, US military officers and diplomats in the region contend that he remains a target worth pursuing.

“Is Joseph Kony a direct threat to the United States? No,” said Scott DeLisi, the US ambassador to Uganda. “He’s not targeting US citizens. He’s not targeting US embassies. He’s not al-Qa’ida.” But, DeLisi said, Kony merits US involvement because his malign behaviour runs counter to “our core values.”

The US military’s journey to the camp here has its origins in the same young activists who created the “Kony 2012” internet video, which blasted into American public consciousness in the spring of that year.

The film-makers, three young friends from San Diego, started campaigning against Kony a decade ago after making a movie about “night commuters” – children in northern Uganda who walked for hours every evening to sleep away from their homes because they feared abduction by the Lord’s Resistance Army. They established a non-profit group called Invisible Children and screened their documentary at hundreds of high schools and colleges, exhorting viewers to write members of Congress and raise money to aid Kony’s victims.

In 2008, after peace talks between Kony and the Ugandan government collapsed, Invisible Children began to advocate for a more robust US response to assist African nations in pursuing him. A bill calling for greater US efforts to disarm the Lord’s Resistance Army – but stopping short of requiring the deployment of US troops – was signed into law by President Obama in May 2010, prompting the State and Defence departments to dispatch teams to Africa to study options for increasing US involvement.

Although the activists cheered Obama’s decision in October 2011 to send 100 US military advisers, they recognised the White House would need ongoing political cover. Senior Defence Department officials told Congress the mission would last for months. But Kony isn’t an easy man to find.

The following March, Invisible Children released Kony 2012 the 30-minute video in which Jason Russell, one of the group’s founders, delivers a plea for a sustained campaign to pursue the rebels. Within a month, it had been viewed 88 million times.

The American advisers wanted to get to work as soon as they arrived. But the US Embassy in Kampala, the Ugandan capital, refused to permit the advisers to leave their bases. Under rules set by the White House, decisions about what the US troops can and cannot do rest not with the Pentagon but with the State Department. And State, in the view of one Special Operations officer involved in the mission at the time, “didn’t want to take any risks.”

DeLisi, the ambassador in Kampala, said the restriction was imposed because the Ugandan government feared that US troops would swoop in, snatch Kony and deprive it of credit. “They had to see that we are not here for a headline, we are not here because of a video,” he said.

As the advisers set out to assuage Ugandan worries, Invisible Children’s field staff urged them to focus on encouraging rebels to defect. Many had been forced to fight at gunpoint. Life on the run in the jungle is miserable. Those who had made it out in recent years said that many others also want to flee but that Kony had convinced them they would be killed or imprisoned by Ugandan authorities. The American activists saw an opportunity: the Special Operations troops could focus their energy on air-dropping leaflets to encourage defections and driving around to persuade villagers in the Central African Republic to welcome those forsaking Kony.

US forces initially scoffed at the idea. But locating rebels to kill or capture proved far more difficult than the soldiers expected, and US officers began to come around on defections. They now regard peeling away rebels as the most effective way to weaken Kony.

Although the Ugandans eventually lifted their ban on joint patrols, the mission began to spiral downward this year. At the outset, the State Department had wanted the military to work with more than the Ugandans – US diplomats believed it was essential to train troops from Congo, South Sudan and the Central African Republic, all of which had been affected by Kony, to mount a co-ordinated campaign and increase regional ties.

But despite repeated efforts, Congo’s government, which does not regard Kony as a significant threat, refused to commit troops – or allow Ugandan forces to operate within its borders. The South Sudanese were slow to offer personnel, and when they did, the US was slow to start training.

The biggest blow came when militiamen toppled the Central African Republic’s government. After the coup, the Ugandans stopped searching for Kony in the Central African Republic because of concern they would be attacked by the militiamen.

The US military command responsible for Africa also began to lose enthusiasm. With al-Qa’ida militants asserting themselves across North Africa, commanders worried about tying up so many Special Operations troops on Kony. They proposed scaling back the effort to simply train Ugandan forces in Uganda, shutting down newly constructed bases in South Sudan and the Central African Republic.

Obama was not eager to retrench. “We need to get this guy,” he told leaders of Invisible Children, Resolve and the Enough Project, another group that has drawn attention to Kony’s atrocities. A senior administration official involved in Africa policy said the military still would prefer to downsize the effort, “but they sense the political wind and they’ve concluded that the best way out is through Kony.”

The September raid may have been a tactical failure, but US commanders view it as a strategic victory. For the first time, the Americans’ renewed vigour was matched with meaningful contributions from Congo and South Sudan – and critical leadership from Uganda, which has resumed hunting Kony in the Central African Republic.

For the Americans, the breakthrough was the result of patience and diplomacy. Instead of acceding to US requests for co-operation, Congo’s government embraced the creation of a regional task force led by the African Union. The South Sudanese agreed to participate, as did the Ugandans, who saw the task force as a way to resume operations in the Central African Republic. Although it was not part of the original US plans, American diplomats and commanders jumped on board, viewing it as the most viable way to get them working together.

Kony’s army has not perpetrated a large-scale attack since the US deployment commenced. His principal aim now appears to be avoiding his pursuers.

“For all intents and purposes,” Leahy said, “the LRA is a defeated force.”

And therein lies the challenge for the US military. If Kony’s ranks were larger and more active, American officers think they would be on his tail. “He’d be on the radar,” one said. “We’d be picking up his [communications]. We’d be tracking his movements.” Instead, “we’re on our own version of the hunt for [Osama] bin Laden, in triple-canopy jungle, with less resources.”

As a consequence, US commanders have concluded that the most critical step in getting to Kony is not training the African forces, but pinpointing his location. Although reports from villagers and defectors have been helpful, the US military has increased the frequency of drone and other surveillance flights over the Central African Republic. “He’ll pop up,” the officer said. “It’s only a matter of time.”

© The Washington Post

Congo rebels are ‘close to defeat’

The UN representative for the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has said that the M23 rebels have almost been defeated.

The country’s army, which just one year ago abandoned its posts and fled in the face of an advancing rebel force, has succeeded in taking back a strategically important city.

In what appears to be a turning point in the conflict, the civilian population of Rumangabo, which reportedly suffered grave abuses while under the control of the M23 rebels, poured into the streets to welcome the soldiers, running alongside their tanks.

Martin Kobler, the UN special representative for the DRC, briefed the UN Security Council and told them “we are witnessing the military end of the M23”, according to French UN ambassador Gérard Araud.

He said the rebels had abandoned most military positions in the east and were now confined to a small triangle, close to the Rwandan border.

AP

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments