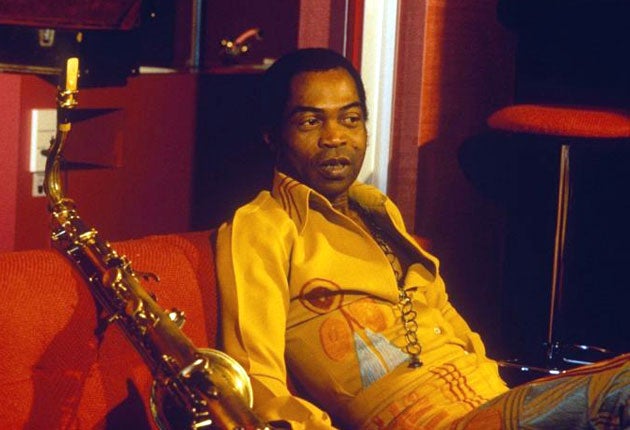

Still struggling – Fela Kuti's family fights on

The legendary nightclub that carries on the family tradition for music and protest has been shut down once again by the Nigerian authorities, angered by its activism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first time the Nigerian authorities shut down Africa's most famous nightclub, they sent 1,000 soldiers to raze the place to the ground. This time a warning letter and some police tape were enough to close the doors to the Afrika Shrine in Lagos, the second coming of Afrobeat legend Fela Kuti's controversial music mecca.

In 1977 Nigeria's military ruler Olusegun Obasanjo wanted to send a devastating final message to his most persistent critic before handing power to a new government. The message was delivered in a hail of gunfire, beatings and rape that culminated in the protest singer being dragged from the building by his genitals, while soldiers killed his 78-year-old mother by throwing her out of a window.

This time Lagos's governor decided that the "noise, street hawkers and illegal parking" were causing a nuisance. A letter was delivered to the new premises, only a stone's throw from the old ruins and run by Fela Kuti's eldest daughter Yeni Kuti and his son, the musician Femi Kuti.

"They made all these complaints and said we had 48 hours to address them and then they closed us down the next morning at 9am," she said from Lagos. "They didn't even give us a chance to react."

The original Shrine, which was at the heart of Fela's Kalakuta (Swahili for "rascals") Republic, was a place where everyone from Paul McCartney to James Brown, Gilberto Gil and Hugh Masekela came to hear for themselves what was hailed as the "best live band in the world".

The latest closure is more likely to sting a newer generation of musicians such as Damon Albarn and Flea of the Red Hot Chilli Peppers, who joined forces with leading African artists to headline a festival at the New Afrika Shrine last year.

It is also testimony to the Kutis' enduring ability to get up the nose of Nigeria's authorities, a pastime that Fela excelled at more than perhaps any of his compatriots.

His son, Femi Kuti, currently touring the US, is helping to keep Afrobeat alive in a cleaner-cut version of his prodigiously promiscuous, polygamous father who lived in a cloud of marijuana smoke.

But Femi's tour manager, Chris Markland, says he may have annoyed authorities just like his father.

"The Kutis have been campaigning to have reliable electricity supplies to the area of the Shrine and Femi has been very vocal in his condemnation of the government's attitude about this and uses his shows at the Shrine as a vehicle to get this message out to a bigger audience."

Whether the current wrangle is over electricity, street hawkers or even the desire of Babatunde Raji Fashola, the Lagos state governor, to change the face of one of the world's most chaotic megacities, it is nothing in comparison with the battles fought by Femi's father.

Fela Kuti was arguably the most influential African musician of the 20th century. Along with virtuoso drummer Tony Allen, he gradually developed his own style of music known as Afrobeat, merging Ghanaian highlife with jazz, funk and native Yoruba music, all delivered in Pidgin English to reach the widest possible African audience.

More than that, Fela was the embodiment of counterculture during Nigeria's dictatorships of the 70s and 80s. John Collins, an author and expert on West African music who knew and worked with the singer, says: "His songs went much further than protest singers such as Bob Dylan, James Brown or Bob Marley."

In his new book Fela: Kalakuta Notes, Collins points out that he didn't hide behind generalisations like "the times they are a-changing", or sing about the evils of "Babylon". "Fela's songs not only protested against injustice but often fiercely attacked specific agencies and members of the Nigerian government."

His greatest hits were a catalogue of assaults on those exploiting ordinary Nigerians.

He wrote songs like "Zombie", a rebuke to the army which compared Nigerian soldiers to robots, and "ITT International Thief Thief" where he attacked the US phone company of the same initials.

After his mother died in the fall from the assault on Kalakuta, the singer, who liked to be known as Black President, delivered her coffin to the army barracks. As on so many occasions, he was beaten for his pains and responded by writing "Coffin for the Head of State".

And yet in the West, his family complain, he is still remembered more for stunts such as marrying 27 dancers from his entourage in a single day and the strange practices of his Ghanaian spiritual adviser Professor Hindu. Other critics complain that songs like "Mattress" reveal him as a misogynist.

What these views ignore is the remarkable stubbornness of the classically trained London Trinity College of Music graduate, who could have lived a millionaire's life anywhere in the world but chose to stay in Lagos. Despite his fame he was repeatedly thrown into jail, beaten and tortured and yet kept up a constant polemic against Nigeria's corrupt, autocratic rulers. In 1979 he even founded his own political party and attempted to run for president before predictably being banned from the ballot. He died in 1997 of an Aids-related illness.

Politics is an ambition shared by another of his sons, Seun, a recording artist like his father, who plays regularly at the new Shrine with Egypt 80, his father's old band.

"My vision is to lead Nigeria. But it's a dream," he said in a recent interview. "We need something new in this country."

For now the club "built like my father's Shrine", according to its manager, Yeni, has been sealed off with tape since last Tuesday and anyone who enters is "risking their life".

The hundreds of street hawkers that congregate nearby are still there, unmolested by the authorities who cited their activities as the reason for closing the venue.

"I've been in a depression," Yeni said. "I've tried everything. I keep on wondering if we're in a democratic government or if we've got a military government."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments