Nelson Mandela funeral: A final farewell as Madiba is buried at his ancestral home

African leaders and old friends of Nelson Mandela led solemn tributes as his body was buried after a week of commemorations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The wind blew gently through the valleys, the sun shone, apple blossoms floated in the air as Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was laid in his final resting place, the earth of the Transkei from where he had sprung.

The last acts commemorating the life and death of probably the most famous man in the world were serene and peaceful, in sharp contrast to the tumult, rancour and extraordinary international attention of the last 10 days.

Instead the ceremony at Qunu, where Madiba, as his fellow countrymen and women call him, had spent much of his youth, was about remembrance of things past, looking back to a time of unity, solidarity and hope. The disillusionment with current politics – so publicly expressed in the relentless barracking of Jacob Zuma as he tried to give his keynote speech at last week’s memorial – was kept very much at a distance.

Perhaps as a precaution, President Zuma began not with a speech, but a song, the haunting and lovely “Thina Sizwe” or “We the Nation” – a revolutionary hymn no one was going to boo.

Graça Machel and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Madiba’s widow and his former wife, were among the first to join in, both wiping away tears, as hundreds of people followed, lifting their voices and filling the vast marquee where they had gathered.

For the third time in as many days, President Zuma appeared to acknowledge that there were causes for resentment. Addressing the departed leader, he said: “Your long walk to freedom has ended in a physical sense. Our own journey continues, we have to ensure the poor and working class truly benefit from fruits of democracy you had fought for. We have to ensure we deliver a decisive blow to poverty, to continue working to build the kind of society you worked tirelessly to construct.”

In truth, however, there was little danger that the chaotic scenes at Soweto’s football stadium in front of 91 world leaders would begin again. The mood was altogether different, one of avoiding confrontations: the controversy over the alleged lack of invitation to Desmond Tutu, an old friend of Mr Mandela, had been resolved, with the Archbishop making the journey to the graveside alongside fellow clerics.

US President Barack Obama had been the star at the memorial service in Johannesburg last week. Prince Charles and Prince Albert of Monaco, the Reverend Jesse Jackson, Oprah Winfrey and Sir Richard Branson, the actors Idris Elba and Forest Whitaker, came to pay their respects. Also present were European political movements which had given support in darkest times, such as the Basque separatists, and Sinn Féin, represented by Gerry Adams.

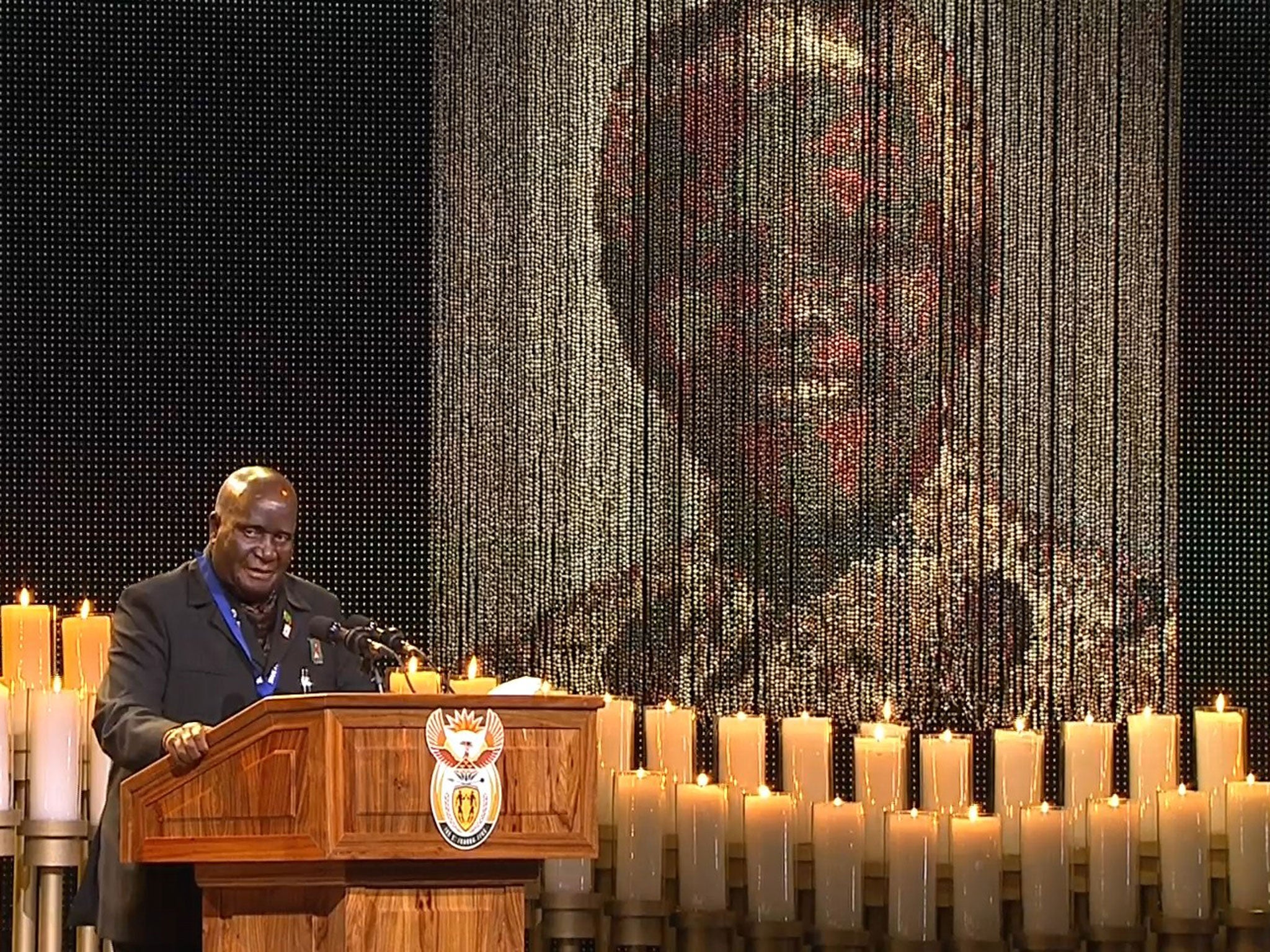

But none of them were expected to speak. Those who did were all African, and most of them had known the founder of modern South Africa for many of his 95 years, which were marked by the number of candles under a portrait of him. The current leaders of Tanzania and Malawi, who had not known him for that long, stressed how he had been an inspiration in breaking the chains of colonialism, and former comrades in arms in the African National Congress (ANC) recalled the years of struggle.

There were reminders of sacrifices made to win fundamental rights from an often vicious racist regime. One of the most poignant addresses was given by Ahmed Kathrada, who had been with Mr Mandela for 26 of the 27 years of his incarceration in Robben Island. He recalled “the tall, healthy and strong man, the boxer; the prisoner who easily wielded the pick and shovel at the lime quarry”. Visiting him just before his death, he found “this giant of a man, helpless and reduced to a shadow of his former self. He tightly held my hand until the end of my brief visit. It was profoundly heartbreaking.”

Speaking to Mr Mandela directly, he continued: “It is up to the present and next generations to take up the cudgels where you have left off. It is up to them to deepen our democracy, defend our constitution, eradicate poverty, eliminate inequality, fight corruption; above all, they must build our nation and break down the barriers that all still divide us.”

Mr Kathrada had regarded Mr Mandela as “Madala”, an older brother, he said, and the late Walter Sisulu, another giant of the ANC, as a father. “Now they are both gone, I don’t know what to do, my life is in a void, I don’t know who to turn to,” said the redoubtable 84-year-old campaigner, a man whose determination and fire was admired by Madiba. His voice trembled as he spoke.

Kenneth Kaunda, the President of Zambia, whose state was a vital source of support to South African liberation movements, drew laughter by repeatedly referring to Afrikaners as “Boers”, a word not considered suitable in the politically correct lexicon at a time when the theme is one of reconciliation and forgiving the past. He spoke of the hypocrisy of the apartheid rulers, preaching Christianity, while keeping fellow men and women in subjugation, and went on to contrast it with Mr Mandela’s own Christian values.

However, although the ceremony was Christian, the funeral was steeped in the rituals of the former President’s Xhosa tribal heritage. He was due to be buried at noon, “when the sun is at its highest and the shadow at its shortest”, Cyril Ramaphosa, deputy leader of the ANC, had said during the proceedings.

This was missed because the event, like every other in the last week, overran. But there were other customs of the Thembu clan, to whose royalty the Mandela family are related, which are said to have been adhered to. An ox was slaughtered, and Mandela’s body was wrapped in a lion skin and told what is being done to it, while elders communed with the spirit.

Nokuzola Mndende, director of the Icamagu Institute for traditional religion, claimed this process was followed. “The body must be informed of whatever is happening before the funeral. The body must rest for one night in his family house before the burial. He must then be told, ‘Madiba, we are now burying you.’ This is a process showing deep respect for the deceased,” she said.

After being kept overnight in the Mandela home, the casket was taken to the ceremony on a gun carriage draped with the South African flag, and placed on a lectern stood on a carpet of black and white cow hides, with gold arches above. Outside, there was a 21-gun salute and a flypast of warplanes in a “missing man formation”, used to salute a fallen pilot. Xhosa warriors were at the graveside to perform a dance to send the departed on his journey into the afterlife.

There were some complaints from the public outside about lack of access to the ceremony, a lingering issue in Qunu. More than 4,500 guests had been invited, but some of the seats had remained empty. Seeing this on television, Mandisa Nobanzi, who claimed a distant relationship to the Mandela family, had rushed out to see whether she could get in.

“Everything outside here has involved the famous people, important people, but this is home and we should have been given a chance to see him and say goodbye,” she protested. “There were lots of seats which have not been taken, we could see that. In fact some of the soldiers on duty were sitting on them. There should have been some reserve tickets for local people. It is a scandal that there were empty seats for such an important occasion.”

Others had travelled hundreds of miles with no expectation of being anywhere near the funeral. Craig Wilkinson had arrived from Pretoria with his wife Ann and three children, a drive of nine hours. “We tried to see [Mandela] when he was at Union Buildings [lying in state] in our city, but we left it until the last day and simply couldn’t get in. It’s the weekend so we could come. We felt it was important, as white South African life could have been very different for us if Mr Mandela had not managed to stop a civil war breaking out. We knew he was going to die, but we do owe him a lot.”

There was, however, a prevalent feeling that a time had come for closure. Nandi Mandela, a granddaughter, said in her address: “Go well Madiba, go well to the land of our ancestors, you have run your race. We shall follow the lessons you taught us throughout our lives.”

Remembering the man they knew

“The struggle Tata Madiba led against the apartheid system was not just a struggle against racial inequality, but a struggle against all forms of oppression against humanity; a struggle for democracy and human dignity… I wish to therefore appeal to all South Africans to remain united and continue to be a rainbow nation for this is what Tata Mandela cherished. It is our hope and prayer that South Africa will remain a country of all people regardless of race, colour, religion and tribe.”

Joyce Banda, President of Malawi

“I first met Madiba in 1946; that’s 67 years ago. I recalled the tall, healthy and strong man; the boxer, the prisoner who easily wielded the pick and shovel at the lime quarry on Robben Island… What I saw at his home after his spell in hospital was this giant of a man, helpless and reduced to a shadow of his former self.”

Ahmed Kathrada, who spent 26 years as a prisoner with Mandela at Robben Island

“He went to school with bare feet and yet rose to the highest office in the land… It is in each of us to achieve what we want in life. His life is a story of resilience.”

Mandela’s granddaughter, Nandi Mandela

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments