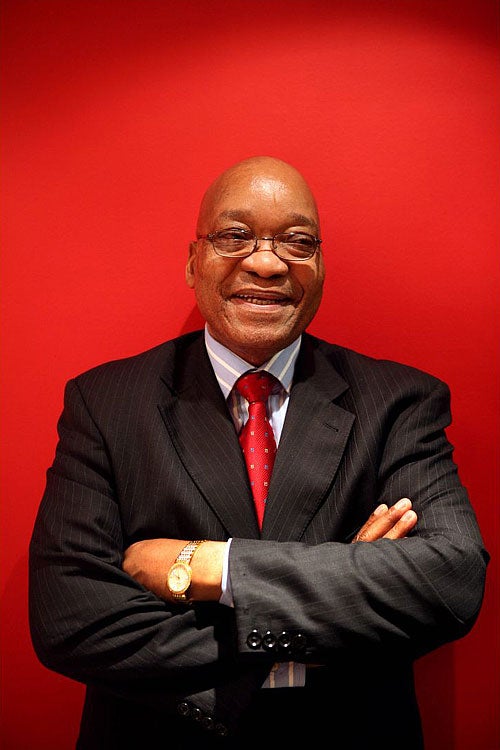

Jacob Zuma: President in waiting

Beaten, tortured and exiled under apartheid, Jacob Zuma arrived in London this week to a hero's welcome. He tells Ivan Fallon of his high hopes for South Africa

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jacob Zuma passed through London this week in a whirlwind of interviews, visits, and breakfast, lunch and dinner meetings. Everyone wanted to meet the man widely expected to be the next South African president, and meetings were heavily over-subscribed with businessmen and politicians almost standing in line.

A group of South African businessmen, representing wealth running into tens of billions, fought to be in the same room as him. He dropped in on Gordon Brown, met newspaper editors, was interviewed by Jon Snow and did the statutory bad-tempered session with the Today programme.

Although he still has nearly a year to run, a trial to be endured and an election to be won, he was accompanied by an entourage as large as a full head of state – and London treated him as such. A year from now he may well be just that, settling himself, after a grand inauguration, into the Herbert Baker-designed office in Pretoria once occupied by Jan Smuts, P W Botha, F W de Klerk and of course his hero, Nelson Mandela. Or he will be in jail. There are not many options in between.

He is already the president of the African National Congress (ANC), which mustered more than 70 per cent of the national vote last time around, and should win another landslide in the elections next year. Until that time, he is not president of the country and Mr Brown, who is intrigued by him, met him as party leader to party leader, and not as two heads of government – the protocol didn't allow that.

In the normal course of events, Mr Zuma, 65, should automatically succeed to the throne which the reclusive and isolated Thabo Mbeki will reluctantly surrender in 2009, having served the maximum 10 years. But nothing in South African politics is ever simple, and in the case of Mr Zuma it is more complicated still. Although he humiliated President Mbeki in the party leadership election in December, Mr Zuma still has a huge hurdle to cross before he can assume power: a corruption trial which starts in August. If he is found guilty he may have to watch the election from behind bars.

None of this seemed to bother him this week, and after several hours in his company, you feel that nothing very much shakes his good nature and imperturbability. Dressed in sober suit and tie, ratherthan the Zulu leopard skins in which he has been widely pictured, he comes across as an elegant and worldly man, relaxed, humorous and comfortable in his own skin. He is remarkably fluent, speaking perfectly grammatical English with a less pronounced accent than either Mr Mbeki or Mr Mandela, both of whom spent some time in London.

Physically he is smaller than I remembered, the same height as Mr Mbeki but a full head shorter than Mr Mandela, and not so portly as his pictures show. His completely hairless head gleams like polished mahogany and his face bears the distant scars of his tribal initiation 50 years ago.

Like many Zulus, he is a gifted raconteur and in the four months since he was elected party leader, Mr Zuma has been on a mission to persuade the white population – and the outside world – that his purpose is "to build and sustain a future of hope for all South Africans".

In some ways, his many critics in the build-up to the Polokwane conference in December can be forgiven for their fears and suspicions. Mr Zuma has certainly led what can only be euphemistically called a "colourful life". He has at least four wives and more than 20 children. He has faced two trials in the past two years, one for corruption, the other for rape, and still faces another. He has some dubious friends, several of them already in jail for corruption.

On the other side of the coin is his impeccable ANC credentials and qualifications for president. He has been successively a trade union activist, a struggle hero, served 10 years on Robben Island and did his combat training in Russia. His record in the party's hierarchy is impressive: membership of the ANC's policy-making executive council from 1977, service on the political and military council, 15 years in exile with frequent covert visits to South Africa, and then a triumphant return in 1990 to meet Mr Mandela and start the negotiations which led to the release of all political prisoners. And then every rung on the ANC ladder, including the deputy presidency before attaining the presidency.

He was hugely important in the months leading up to the 1994 elections, and Mr Mandela has given him much of the credit for stopping the bloody fighting between ANC supporters and Chief Buthelezi's Inkatha Freedom Party, which threatened to engulf the country in the run-up to the polls.

He has also fought the allegations of misconduct and corruption. Amid widespread accusations that the charges against him were driven personally by Mr Mbeki, seeking to destroy a rival, he was acquitted in the rape case (although he admitted having sex with the girl, a family friend who is HIV-positive). He was also acquitted on the first corruption charge, the judge contemptuously throwing out an ill-prepared prosecution case which was also seen as politically inspired. The same corruption investigation, pursued with what he calls a "suspicious" zeal by the authorities for the past eight years, has led to a second corruption trial for which he is now preparing.

Mr Zuma's charm campaign to counteract the poor image and truly awful publicity has been remarkably successful. He has set out the toughest stance yet on crime, insisting the laws will be strengthened, the police force will be increased (under Mr Mbeki's plans it will already double from 2000 to 2010), and police will be encouraged to be much tougher, even to shoot first and ask questions later. He has even hinted he would not discourage a move to bring back the death penalty.

He has also promised to continue the widely praised economic policies which have caused the economy to boom in recent years, and to keep the same economic team in place if they will agree to serve. He has committed to a major new initiative on HIV/Aids, for which he was previously responsible before Mr Mbeki sacked him as deputy president of the country, and on tackling the Zimbabwean President, Robert Mugabe, where he has been much more forthright than Mr Mbeki. "It is a crisis," he says, in contrast to the South African President's bland "there is no crisis".

Despite the charges against him – and some of the mud has stuck – he insists he will stamp down hard on corruption, which he adds was "never raised as an issue during apartheid", although it was rife. "I will not tolerate corruption," he says firmly.

He seems to have done the trick. The white population, fearful of him a year ago, now loves him. Senior Afrikaners have hailed him as the great hope not just of South Africa but of the whole region, and in private talk of him as even better than Mr Mandela, capable of taking their beloved country into new and sunlit uplands.

"I am now more optimistic about South Africa than I have ever been," said one businessman after listening to him on Tuesday.

Others look at it in simpler terms. "If he's tough on crime, that's enough for me, regardless of the rest," says the wife of one of South Africa's billionaire Afrikaners.

It is a long way from the herd-boy who grew up in rural Zululand with 12 brothers and sisters. His Zulu roots go deep, and he is very proud of the culture, relishing the stories the old people told of Shaka and Cetshwayo, and the Zulu wars against the British when 20,000 Zulu troops destroyed an entire Welsh regiment in three hours. "As a herd-boy, one of the things you do is prepare to become a warrior, and therefore to learn to stick-fight, and you are taught how a man must behave, how a man must be brave, and I went through all the rituals. You learn the Zulu culture."

In Durban, where his mother went as a domestic worker after his father died, he soon became an active trade unionist and a member of the ANC shortly before it was banned in 1960. He was an early recruit to Umkhonto we Sizwe, "Spear of the Nation", set up by Mr Mandela and other leaders to wage a campaign of armed sabotage against the South African state.

"The debate among the youth was: what is the use of the non-violent policy which was being pursued by the ANC when even if we were protesting, unarmed, we were shot at by the police?" he says now. "So we felt that the time had come to wage an armed struggle."

Inevitably he was arrested, in 1963, savagely beaten by the police in Pretoria and sent to Robben Island for 10 years. He was just 21 years old. "Prison conditions were not pleasant at all," he says with one of his characteristic chuckles, as if it were a holiday camp which had not met expectations.

Mr Mandela and the top ANC leaders would later turn Robben Island into a political university, but Mr Zuma claims he actually began the process of political education among the prisoners. "My sentence was a relatively short one. Others were doing 20 and even 30 years [Mr Mandela did 27 years in prison, most of them on Robben Island]. So there was time and an opportunity to educate ourselves. There were people there who could not write their names and learnt. It was the beginning of political education on Robben Island. This was very important because if you came in there, you must come out much better educated politically."

Did he ever dream at that stage he might become the leader of the ANC and potentially the president of the country? "Not at all. All that I dreamt of in Robben Island was that one day I'd be a free man in South Africa – that was the main objective. In the ANC we don't have that kind of dream – we wanted to prepare ourselves to undertake any task that the ANC gave us."

He served his full 10-year sentence but was only out for two years before he had to flee again, this time to Swaziland and later Mozambique where he learnt about the 1976 Soweto uprising. From the age of 21 to 48 he was either in prison or exile, so his return in 1990 was all the more welcome.

It is a remarkable story and an extraordinary preparation for what is probably the most important job in Africa. He is wholly philosophical about the trial, and remarkably without bitterness. "If the state says you must be charged, then no citizen is above the law. Courts are there to produce a verdict and you are not guilty until the court says you are guilty." But he then adds darkly: "It does raise suspicions that one individual should be charged and charged again over a period of eight years."

Watching him this week, being convicted at the trial and going to jail is the last thing he expects to happen. He is already setting out his vision for South Africa – it's a very sunny one.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments