At a ceremony in Sierra Leone, a sudden jolt of violence, and a bloody 'corpse'

Ten years after Britain's intervention in west Africa, Joan Smith has a brief, intimidating encounter with one of the secret societies terrorising the country

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

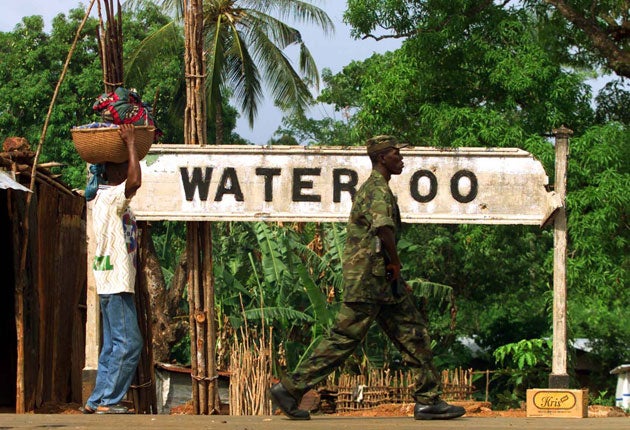

Your support makes all the difference.It was a swelteringly hot day. Under a clear blue African sky, the people of Waterloo had been gathering since 8am on the edges of a big square which had been cleared for the construction of a state-of-the-art library. Early arrivals managed to find shade under awnings, but the rest were exposed to the pitiless midday sun. The mood was festive, with drummers, dancers and stilt-walkers performing as the crowd waited for politicians to arrive from Freetown to celebrate the beginning of work on the library.

I had been asked to sit with the dignitaries, which meant I had to leave behind my photographer, Fid Thompson. I wasn't worried, assuming that the worst either of us would have to cope with would be long speeches. After them, I began gathering my belongings – and suddenly all hell broke loose. Before I knew what was happening, I was on my own in the centre of an angry mob. Hands shot towards me, and I was jostled as men in costumes and masks demanded money. I began to panic: why had I been left alone? Where were the ministers, the MPs, the president's representative? They were long gone, hustled away in their limos as the atmosphere began to sour.

In Sierra Leone, it's not uncommon for public events to end in an outbreak of disorder, which is why I'd earlier seen police patrolling the site in such numbers. At that moment, a policeman in full riot gear began pushing his way towards me, thrusting the mob aside with a long baton. He was joined by another, dressed identically in blue overalls and a helmet, and I struggled to reach them. Together they got me out of the tent and I stumbled on the uneven ground. The mob rushed me again and another policeman ran up, brandishing a gun above his head.

The crowd fell back and the cops formed an escort, hurrying me to the road which runs past the building site. I had no idea where Fid was, my mobile didn't work and I hadn't a clue what to do next. I spotted a local politician I knew, and ran to him to ask for help. He turned his back on me with a shrug.

Fid appeared with two women guests from the UK. They were ashen, and I couldn't immediately understand what they were saying. Someone gasped something about a corpse, a man whose throat had been cut, and Fid held up her camera: on the screen was a photograph of a man naked to the waist, spattered with blood and waving a knife.

She said he'd been dragging what appeared to be a dead body wrapped in a shroud, but she was threatened when she tried to take pictures of the corpse. The police kept back, clearly too scared to intervene, and the only thought in my head was that we had to get out before anything worse happened. I spotted the minibus we'd been using the previous day and we ran towards it, pulling open the doors and piling inside. The driver took off, hurrying us to a house on the other side of Waterloo which belongs to one of the town's MPs.

Over the next couple of hours, as the adrenalin drained from my body, I asked everyone I met whether there had really been a killing at the construction site. One man tried to reassure me: the dead man was terminally ill, he said, and had been killed the previous evening as a sacrifice to ensure the success of the project. Another shuddered at my question, mentioned secret societies and clammed up, refusing to say more.

When the MP returned to his house, I told him what had happened and he rocked with laughter. "It's just a ritual," he chortled. Later in the day, someone else claimed to have seen the "corpse" on his feet and dancing, but it was clear my questions were unwelcome and some kind of damage-limitation exercise was going on.

No one wants to talk about secret societies in Sierra Leone. They wield enormous power but few people are prepared to admit that they belong to one, let alone reveal its workings. Yet the mini riot at the construction site and the blood-stained man dragging a "corpse" seemed to me to have no rational explanation other than as a demonstration of secret-society power.

My hunch was confirmed not long after I got back to London in an email from a friend in Sierra Leone. She told me she'd just attended the opening of an iron-ore mine, where the ceremony was once again disrupted by an ululating mob. In their midst was a half-naked man, covered in blood and brandishing a knife, whom she identified as a member of the all-male Poro secret society. "I really don't know what to think about these secret societies," she wrote. "I am inclined to think the body at Waterloo was not a real corpse. But I have no evidence to the contrary."

A British Home Office report on Sierra Leone noted that Poro "has considerable local and national influence [and] would appear to be able to organise nationwide.... In some areas the membership would appear to comprise all of the adult male population." It said that Poro initiation ceremonies involve scarification, and mentioned accounts in the Sierra Leone press of intimidation and "provocative demonstrations" of the kind I saw.

My father was stationed in Freetown during the Second World War, when he served on Atlantic convoys, and he talked about Sierra Leone endlessly when I was a child. Years later, the country impressed itself on my consciousness again when my friend Robin Cook spoke about it warmly, convinced that his decision to send British troops in May 2000 had put an end to its savage civil war. Cook's intervention was crucial.

On my first visit to Sierra Leone in 2008, I met people in Freetown who'd watched British troops arrive, sending the coked-up rebels of the Revolutionary United Front – the teenage soldiers who chopped off arms and legs in the film Blood Diamond – into panicked flight. The war ended officially two years later, and since then international aid has poured into the country. It's the biggest per capita recipient of aid from the British government, which spent £48.3m on projects to improve the country's health, education and governance in 2008-09.

Aid to Sierra Leone is a controversial subject because the country is notoriously corrupt. President Ernest Bai Koroma is regarded as honest; he was the first president to declare his own assets, and he signed a wide-ranging anti-corruption law two years ago. But two government ministers were sacked last November; one of them, the former health minister, was immediately indicted by the country's anti-corruption commission.

The UK's National Audit Office recently looked at projects in Sierra Leone funded by the Department for International Development and found no evidence of money being siphoned off. But there is a perplexing incongruity between the amount of international aid going into the country and the everyday lives of most of its inhabitants. Seventy per cent of the population live below the poverty line; just over a third don't get enough to eat each day; maternal and infant mortality (one in five children dies before the age of five) are among the highest in the world. Hundreds of thousands of refugees fled to the capital during the civil war and they're still there, living in shacks made of debris and corrugated iron, and picking over rubbish tips to make a living.

Perhaps the most tragic thing of all about Sierra Leone is the knowledge that the government won't act to prevent the needless mutilation of thousands of girls. The men's secret society that disrupts public events has a female equivalent, Bundu, which takes teenage and younger girls into the bush for months at a time to excise the clitoris and "prepare" them for womanhood. Female genital mutilation (FGM) is widespread in Sierra Leone. Unicef estimates that more than 90 per cent of the adult female population has been cut, although other organisations suggest it's more like 65 per cent. It's one reason why one in eight women die during pregnancy or childbirth. In the recent past, politicians in Sierra Leone actively encouraged FGM, regarding it as a vote winner; the wife of a presidential candidate once sponsored the mutilation of 1,500 girls during an election campaign.

Immediately after his election in 2007, Mr Koroma pledged to ban FGM, as other African governments have already done; a few months later, his social affairs minister Haja Musu Kandeh repeated the government's pledge. But the promise hasn't been carried out, girls are still being mutilated, and foreign donors seem curiously reluctant to exert pressure to make the President deliver.

No one with real power wants to take on the secret societies, it seems. I often think about the girls I met in Sierra Leone earlier this year, crowding round me with their favourite books and giggling as they begged to have their photographs taken. They want to be doctors, librarians and hotel receptionists, but in a year or two most of them will be taken off into the bush to be made into "women".

My brush with one of Sierra Leone's secret societies lasted a few minutes, but for the country's women and girls the damage lasts a lifetime.

Sierra Leone at a glance

This West African country was one of the first to become a centre for the European slave trade. At the end of the 18th century, thousands of freed African-American slaves were resettled by British abolitionists and philanthropists in the capital, Freetown.

Rebellions against colonial rule were violently crushed, as the country had rich mineral resources. It gained independence in 1961. An initial period of stability came to an end with the untimely death of the first prime minister, Sir Milton Margai, in 1964. Political coups, corruption, ethnic divides and one-party rule were the norm over the next three decades.

Civil war broke out in 1991 due to government corruption and mismanagement of the country's diamond resources. This was heavily influenced by war in neighbouring Liberia, whose rebel leader, Charles Taylor, helped arm Sierra Leone's Revolutionary United Front. Civilians suffered nearly 10 years of terror, with thousands of children forced to carry out atrocities.

UN peacekeepers arrived in 1999 to help police a peace agreement; the war was declared over in 2002. A UN-backed court opened in 2004 to try militia leaders from both sides. The case against Charles Taylor continues in The Hague. Even now unemployment remains high, law enforcement patchy, and the country has some of the worst maternal and child mortality rates in the world.

Nina Lakhani

Sierra Leone in numbers

75,000 people died in the civil war between 1991 and 2001.

2m more were forced from their homes and many fled to Guinea and Liberia.

10,000 childrenwere forced to fight in the war, forcibly injected with cocaine and other stimulant drugs before they were sent out to abduct, rape, maim and kill thousands of their fellow citizens.

25 per cent of children in Sierra Leone die before the age of five.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments