After the war, the vengeance as rebels seek out 'traitors'

Portia Walker reports from a town paying a high price for supporting Gaddafi

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The empty hallways echo with the sound of a slamming door as gusts of wind blow through the abandoned apartments. On the walls outside, the newly scrawled graffiti reads: "Traitors go to hell." Inside, the rooms smell of death.

As Libya's opposition fighters battle for control of the last parts of the country still loyal to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, these eerie, empty dwellings offer a grim omen of what the future may hold for those who fought for the deposed dictator.

Until a few months ago, the town of Tawargha was home to about 30,000 people. Now only a few dozen men remain, hiding out in a wetlands area, sniping at anyone who approaches. The scrappy young rebels guarding the town say the loyalists emerge occasionally to scavenge for food. "From time to time we capture some of them," Hamza al Taeb said. "Three came to us because of hunger."

It was soldiers from Tawargha, rebels say, that led the months-long assault on Misrata, 20 miles to the south and the scene of some of the bloodiest battles in Libya's seven-month civil uprising. Misratans say that during the struggle for their city, fighters from Tawargha raided their homes and raped women. Many of the claims are impossible to verify, particularly because Misrata is a deeply conservative city where people are unwilling to discuss sex crimes. But what is certain is that the people of Tawargha are collectively paying the price for the crimes their fighters stand accused of.

The new apartment blocks are all empty, their rooms ransacked. Bookcases are upturned and television sets smashed. Animal droppings are dotted on pulled up carpets and a film of dust from the surrounding desert is beginning to build up. In some of the apartments, military uniforms lie discarded on the floor. But in other rooms there are school exercise books and toys from the families who had lived there.

A small flock of sheep wander amid the burned-out cars in the deserted parking area, joined by a pair of goats and a solitary hen, presumably livestock abandoned when the city's residents made their escape as the vengeful rebels approached.

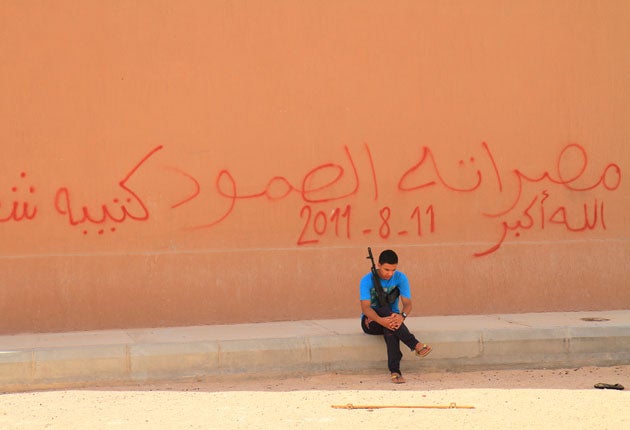

Outside one of the apartment blocks, a group of young men from Misrata loll on cushions. One, still in his teens, smokes a cigarette and carries a Kalashnikov almost as big as himself. Their commander, Muftah bin Nasser, wants the area cleared of the people who had once lived there.

"They invaded Misrata, they abused our people, they raped our women and they burned our homes," he said.

Tawargha's residents were almost all black, and there is a racial undercurrent to the accusations being made. But there are other dynamics at work. The town had long benefited from Colonel Gaddafi's largesse in the form of cash handouts, new housing and other benefits. The mercurial leader would often provide financial assistance to a particular group in order to control the balance of power and offset traditional centres of control.

Still, many of the rebels discussed their dislike for the people of Tawargha in racial terms. Mr bin Nasser said: "Their area is not here. They are not originally from here, they are from the south and they can go somewhere in the south. They caused me to hate all black people."

Over seven months of civil war, shallow fault lines among the Libyan people have deepened into fissures. The leaders of the rebels' interim government are pushing for forgiveness and reconciliation – but they face a difficult task in reconciling some of the people from opposing sides of this bloody battle and preventing the spread of vigilante justice from the many heavily armed militia units within the country.

Amnesty International earlier this month issued a statement highlighting the plight of people from Tawargha, and urging the rebels to do more to prevent racist attacks after residents "were detained, threatened and beaten on suspicion" of fighting for Colonel Gaddafi.

Misratans in particular have earned political capital in the new state for the bravery they showed in defending their city, and it will be difficult to rein in. All of the Misratans The Independent spoke to viewed the return of the people of Tawargha as impossible.

Miftah, a rebel commander from Misrata, said: "Libya is big. They can go to Sabha, Jubra, anywhere."

One Misratan, Mohammed El Taeb, gave the opinion shared by many of the people from his city. "Those people have to take their punishment," he said. "The rebels have witnesses on them and they will be killed. There is no way to forgive them. It is hellfire for them."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments