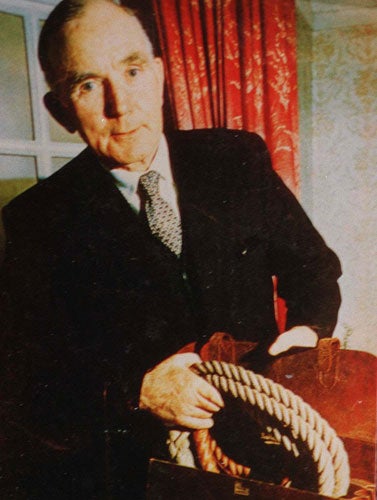

The real story of Britain's most famous hangman

He is remembered as a man of principle. But secret papers unearthed by Cahal Milmo show that Albert Pierrepoint was in fact a money-grabbing fantasist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 3 January 1956, Albert Pierrepoint arrived at Strangeways prison in Manchester to carry out the execution of Thomas Bancroft, a convicted murderer, in what would have been the 436th death sentence to be executed by Britain's most prolific hangman. It proved to be his last engagement as the undisputed master of the gallows.

Such was Pierrepoint's regard for what he described as the "sacred" nature of his duties, it has long been assumed that he stepped down after a crisis of ethics over his role, at a time when the death penalty was being strongly challenged in Britain.

However, documents obtained by The Independent under the Freedom of Information Act reveal that he in fact resigned with an angry tirade at the "meanness" of his employer.

The papers reveal the full story of Pierrepoint's sudden departure from the post he held for 24 years in an atmosphere of mutual dislike and recrimination. They lay bare how the "loyal servant of the Crown" was dubbed a "fantasist" by the Attorney General and investigated for breaching the Official Secrets Act.

Prisoner Bancroft, less than 12 hours to go before his appointment with the noose, received a reprieve. Pierrepoint therefore pocketed a cheque for £4 from the Under Sheriff of Lancashire – less than a third of his normal fee for a hanging.

It provoked the nation's principal executioner into a steaming rage which led to his resignation.

The file, which was supposed to remain unpublished until 2032, also casts a new and unflattering light on Pierrepoint, the former pub landlord who went down in history as a sober tradesman in death with an almost priest-like regard for those whose lives he extinguished and a self-effacing disinterest in the income he derived from his monthly visits to the execution chambers of Britain.

The row over his payment for the abandoned execution of Bancroft coincided with his decision to sell his story to a Sunday newspaper famed for its salacious coverage for £20,000 – equivalent to £400,000 today. He provide a detailed description of his famous executions, including those of the serial killer John Reginald Christie and Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be hanged in Britain.

The serialised articles in the Empire News, which was later merged into the News of the World, provoked fury in the highest echelons of government and drew suggestions that the hangman had resigned his position solely to strike a deal with the newspaper.

A memo in the documents shows that Reginald Manningham-Buller, the attorney general and the father of the former MI5 director general Eliza Manningham-Buller, privately warned the prime minister Anthony Eden that the disclosures were "all very tiresome" and he wanted to see Pierrepoint prosecuted for flouting the Official Secrets Act.

The train of events began when the hangman – the last in a dynasty of state-funded killers that was begun by his father and his uncle – was unable to return to his Lancashire pub after the Bancroft reprieve, due to bad weather. He was forced to stay in a Manchester hotel.

Pierrepoint made a claim for the extra expenses he had incurred, but instead of his full "executioner's fee" of £15 and other costs, the Under Sheriff sent him only £4. In his resignation letter, held at the National Archives in Kew, west London, Pierrepoint wrote: "I must inform you that I was extremely dissatisfied with this payment, and how I regard this kind of meanness as surprising in view of my experience and long service. In the circumstances, I have made up my mind to resign."

Pierrepoint refused entreaties from the authorities to reconsider and rebuffed an offer of the whole amount owing to him, telling a friend that he had signed a deal with the newspaper because "I realised there is no sentiment in business".

Within a month of writing his resignation letter, Pierrepoint put his name to a lurid account in the Empire News of the execution of Christie, the so-called Monster of Rillington Place who killed at least eight women. It detailed how a wardrobe concealing the entrance to the gallows chamber was moved at the last moment.

Pierrepoint wrote: "I hanged John Reginald Christie in less time than it took the ash to fall off a cigar I had left in my room at Pentonville... As I motioned towards [the execution chamber], all Christie's face seemed to melt. It was more than terror. I think it was not that he was afraid of the act of execution. He had lived with and gloated upon corpses. But I knew in that moment that John Reginald Christie would have given anything in his power to postpone the moment of detail."

The hangman added that because Christie began to stagger towards the trapdoor with the noose around his neck he decided to pull the lever "while he had yet half a stride to go".

Manningham-Buller determined such details merited charges against Pierrepoint and the Empire News editor. But a police investigation found there had been no wardrobe in the killer's cell and far from stumbling to his death, he had stood squarely on his feet before being hung. The Attorney General said it was "not without regret" that such "fantasy" meant a prosecution was not possible.

Pierrepoint was left to enjoy his retirement, which saw him become a minor celebrity, hosting coach parties at his pub and writing an autobiography. With an authority that only a man of his experience could wield, he also became an eloquent – but tardy – opponent of the sentence he had dispensed with such adeptness. His record for escorting a prisoner from the condemned cell to the gallows trapdoor was seven seconds. He famously wrote: "Capital punishment, in my view, achieved nothing except revenge."

But the documents show that, in 1956 at least, Pierrepoint retained a large degree of pride in his work and was still ready to act as the steady arm at the sharp end of the death penalty. He told the Prison Commissioners: "I am aware that the other persons on the list [of approved executioners] may not be capable of carrying out an execution to the satisfaction of all concerned. If... an occasion should arise in the future on which you think my services are necessary, I should be prepared to consider an individual case."

Death became him: The life of Albert Pierrepoint

Albert Pierrepoint knew his destiny from an early age. At 11, he wrote in an essay: "When I leave school, I should like to be Chief Executioner."

Following in the footsteps of his father and uncle, Pierrepoint trained in the "British art" of hanging at Pentonville prison in London, calculating the length of rope needed to cleanly break a prisoner's neck.

It was an art at which the tall, dapper Lancashire publican became famously adept, dispensing justice at the rate of one execution a month, all the while clad in his trademark double-breasted suit. At least two of his "clients" were later pardoned – Derek Bentley and Timothy Evans.

Such was Pierrepoint's reputation for efficiency that the British Army approached him to execute Nazi war criminals convicted at the Nuremberg trials. He was flown to Germany to hang 200 prisoners.

In his autobiography, Pierrepoint wrote: "A condemned prisoner is entrusted to me, after decisions have been made which I cannot alter. The supreme mercy I can extend to them is to give them and sustain them in their dignity in dying and in death. The gentleness must remain."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments