The Independent Guide to the UK Constitution: What everyone should know about the most explosive political issue of our time

The UK’s democratic liberties are the envy of the world. They are also precarious. We have no written constitution, and the unwritten traditions on which we rely instead are increasingly being called into question. Human rights, the monarchy, Europe, the sovereignty of Parliament, the formation of governments – are there any first principles on which we can agree? On the eve of the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, Andy McSmith kicks off a week-long series on a subject of vital national importance

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A furious political row over human rights is on the boil. It is not about what those rights should be but over who makes the decision, whether the final arbitrator of the rights of a British citizen should be the British government, or a European court.

When David Cameron agreed to include in the Conservative election manifesto a promise to repeal the 1998 Human Rights Act, he may have calculated that he would be denied a majority in the Commons and provided therefore with a cast iron alibi for dropping the whole idea.

As it is, the newly appointed Justice Secretary, Michael Gove, has no choice but to draw up a British Bill of Rights – something no previous Lord Chancellor has done in the many centuries during which that office has existed – and place it before Parliament to see if the votes are there to get it through. What set this off was a ruling from the European Court of Justice that prisoners in British jails should have the right to vote. Since this is where it all began, it might reasonably be assumed that the purpose of the new act will be to remove rights that people have under European law which the government thinks they should not have, rather than to give any British citizens any new rights.

This then throws up a major complication, because the UK is a signatory of the European Convention on Human Rights. Indeed, the UK and France were the two nations, more than any others, that created the ECHR. The convention is separate from the EU. Created in 1953, it is also older than the EU, and covers every country in Europe except Belarus – including, for instance, Russia, where that brave minority fighting for human rights see it as a valuable safeguard.

If the UK withdrew from the Convention, the effect could reverberate across Europe. Yet if we remain within the ECHR – which is apparently what David Cameron and Michael Gove intend – the possibility remains that someone who thinks that their unalienable rights have been denied by the British courts could still appeal to the European Court over the heads of Britain’s judges. That would then raise the question of whether there was any point to passing a new human rights act at all.

It is up to the Conservatives to sort out the politics of all this. What matters more to most of us is the deeper question of what our “unalienable rights” are, and whether the law will continue to protect them. This is a question on which most people have a clear and broadly accurate general idea, while being hazy about where these rights originate.

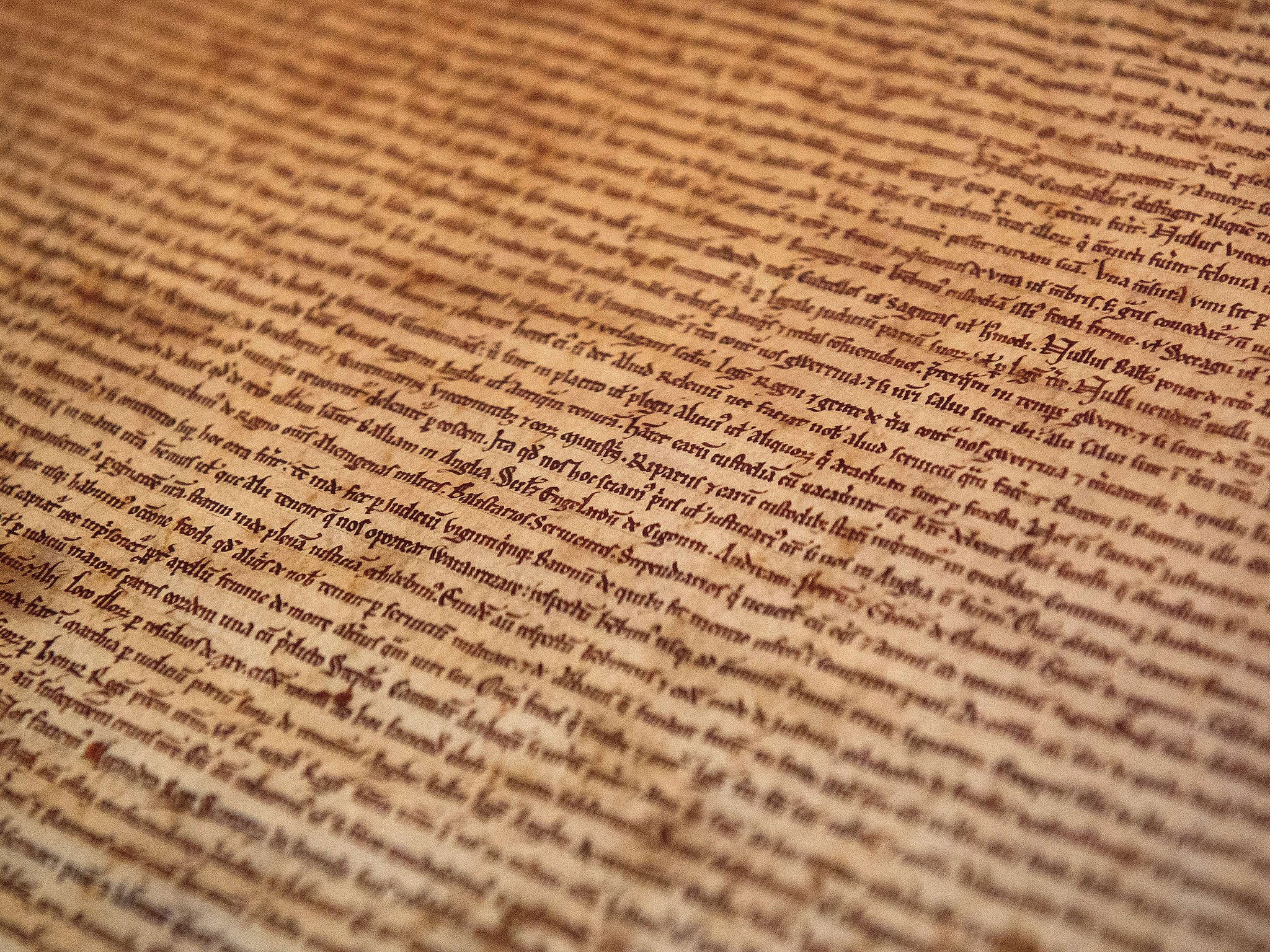

Anyone who does not already know that the Magna Carta was “signed” (when King John placed his royal seal on the document) 800 years ago this month will doubtless be reminded by the celebrations surrounding the anniversary (on 15 June), and will know that in some unspecified way our ancient rights as British citizens spring from that document. But how?

Most educated people in the English speaking world have also heard the famous passage from the 1776 American Declaration of Independence, which was indirectly influenced by Magna Carta. It says: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness…”

Actually, these truths are not “self-evident”. They are not evident at all, for instance, in North Korea, or in parts of the world ruled by religious zealots. When Thomas Jefferson wrote them, he was being deliberately provocative, throwing those words in the face of the British property-owning class who believed that they had a right to hold arbitrary power in check, but did not extend that right to American colonists. Jefferson himself, despite his proclaimed belief in an “unalienable right” to liberty, was a slave-owner.

Yet the fact remains that, in our liberal democracy, we do believe that citizens have unalienable rights – and not just those listed by Thomas Jefferson. Most people in modern Britain would say that a UK citizen has a right to free speech, a right to express their sexuality, a right to belong to any legal organisation he or she chooses to belong to, a right to be paid if he or she is in work; some might add to these a right also to have paid work, and a right to eat, to be housed, to be educated, and to be cared for when old or sick. But the legal document that defines all these rights does not exist. They are certainly not found in Magna Carta, which lists all sorts of strictures that mean absolutely nothing to us – such as “heirs may be given in marriage, but not to someone of lower social standing”; or: “no town or person shall be forced to build bridges over rivers except those with an ancient obligation to do so.”

There is just one section that has resonated through the ages, way down the text in clauses 39 and 40, which say that “no free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land” and “to no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.”

Magna Carta’s purpose was to protect the barons, and to some extent all England’s free men – but not the women, nor the serfs who made up most of the population – from arbitrary rule by a weak, tyrannical king. Its importance is that it set down in writing that there were circumstances in which even the king was subject to the law; and that it was recognised by subsequent kings.

When people refer to the “British constitution”, they do not mean Magna Carta. Instead there is what is known as the “body of law” – the combined total of Acts of Parliament and judgments reached in court cases, which are scattered over countless law books and statutes. None of these has the weight of a constitution in itself; yet taken together they carry too much weight to be easily set aside.

One of the first serious attempts to collect and codify all these judgments, and so give England a written body of constitutional law, was made in the 1760s by the jurist William Blackstone, whose four volumes of Commentaries were read avidly by the USA’s founding fathers.

Some of what Blackstone wrote sounds weird to the modern ear (for example, his assertion that kings could do no wrong); and there have been other heavyweight codifiers since – AV Dicey, Walter Bagehot, even Sir Gus O’Donnell – who are arguably equally significant as authors of what passes for the UK’s written constitution.

Yet it was Blackstone who wrote one powerful sentence that neatly disposed of the idea that any idea of what is good for the public as a whole should ever be a pretext for trampling on individual human rights. “The public good,” he wrote, “is in nothing more essentially interested, than in the protection of every individual’s private rights.”

This week, starting here and and continuing every day until 13 June, the Independent marks the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta’s signing by reviewing the written foundations, such as they are, to what passes for the UK consistution. The series offers a guide not just to the main points of that constitution but also to the documents in which those points can be found. These are big issues. Yet it is arguable that all that matters in our constitution is expressed in that single sentence of Blackstone. It is on its underlying assumption – that an individual citizen’s rights are so important than they take primacy over religious zeal or government policy – that liberal democracy is built.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments