The Big Question: Why are public finances in such bad shape, and how can they be rescued?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

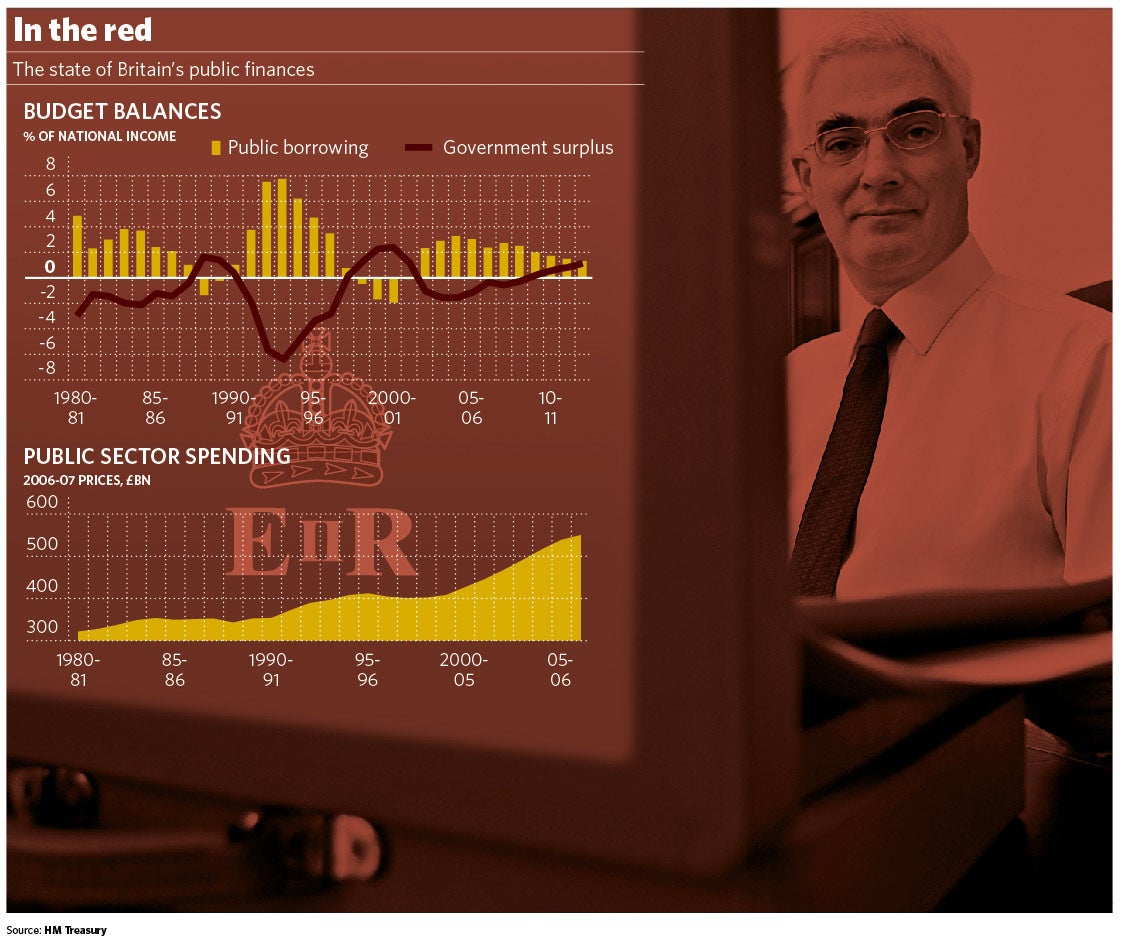

Because as the Chancellor, Alistair Darling, prepares to announce his first Budget, he doesn't have much room for manoeuvre – public finances are in a sorry state. According to some analysts, he would have to raise as much as an extra £9bn to sort out the country's debt problems. Over the next few years, he is also in danger of breaking the two fiscal rules that Gordon Brown put in place for the Treasury. The rules state that Government debt should not exceed 40 per cent of GDP, while borrowing could only be used to finance investment projects, such as the building of schools and hospitals.

So what's the current situation?

Public debt has been rising steadily since 2001. By the end of the month, the Treasury predicts it will hit £542bn – around 38 per cent of GDP. It looks like the Government will need to borrow £40bn more each year until the end of the decade to meet its current obligations. And while the Treasury confidently predicts that debt will stay under the 40 per cent of GDP barrier over the next few years, others aren't so sure. The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) expects public debt to breach the mark by 2009, and also thinks that the Government may have to break Gordon Brown's other golden rule as well.

The situation became worse when the Office for National Statistics decided to add the debt of the nationalised mortgage lender Northern Rock to the Government's blotted balance sheet, a move that could add as much as £100bn to public-sector debt. The burden is only temporary though – it will only stay on the public books until a private buyer is found for the lender's mortgage book. As a result, the Chancellor will only temporarily break the self-imposed debt target.

Is it really that bad?

It could actually be worse. Among all the speculation about the Budget, one thing that can be predicted with some certainty is that Alistair Darling will not be spelling out the real state of public finances today. Sometimes it can be hard to tell exactly how bad the picture is, because some of the Government's biggest liabilities do not even appear on the public books. The most obvious ones are the many Private Finance Initiative (PFI) schemes, the vehicles used to finance expensive projects such as the building of schools or hospitals. One of the key reasons that the Government has been so keen on PFI is that it doesn't need to borrow the capital to build the projects in the first place. Its mammoth public-sector pension deficit is also kept off its books.

What is causing the problem?

Tough economic conditions have played a role. A tightening of credit has impacted on consumer spending, slowing the economy. The most recent dip in public finances was notably caused by declining VAT and corporation tax receipts – both directly hit by falls in economic growth and consumer spending.

Some political decisions had an effect, though. When the world economy was on a surer footing and the Treasury had a surplus, revenue was used for investment in public services – most notably the NHS. But that policy has had an effect now. As Martin Weale, director of the National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR), put it: "Fiscal policy should be about saving up for a rainy day; now we have a rainy day – but no savings."

Are other countries in trouble too?

Global economic conditions have been unkind to many countries. The UK has an almost identical level of debt as a percentage of GDP as France, and less public debt than Germany and the US. Levels of public debt in the UK are also below the average for both Eurozone and OECD countries. It's not surprising then that many have seen poor old Alistair Darling as one of the unluckiest chancellors in recent times, taking the helm at the Treasury at a time when the world hit choppy waters. However, 16 out of 21 comparable industrial countries have been reducing their debts by more than the UK since Labour came to power.

What should he do?

According to two prominent think-tanks, Mr Darling will need to raise taxes in order to meet the challenges raised by the state of public finances. The IFS has said that the Chancellor will have to raise an extra £8bn in tax in order to keep public-sector debt below the 40 per cent mark and bring public finances back into line with the Treasury's future expectations. The NIESR puts the amount needed to plug the hole even higher, at £9bn. Others advise the opposite approach – to ignore artificial debt limits and inject the economy with more cash, either by offering bigger spending plans or cutting taxes.

What will he do?

Raising taxes to such a degree at a time when many people are feeling the pinch of higher bills would not be popular. A significant tightening of fiscal policy is unlikely. Mr Darling may well argue that the deterioration in public finances is just a temporary blip, and that fiscal policy should not contradict the Bank of England's attempts to ease the burden on the economy by holding interest rates. However, the IFS argues that the Chancellor could afford a modest fiscal belt-tightening if the Bank of England offset the move with a cut in interest rates. It's at times like this that the chancellor might be wishing he still held the monetary policy reigns, too. A bout of deficit spending might also be seen as too politically dangerous, allowing Labour's opponents to accuse it of abandoning good economic stewardship in favour of short-term gain.

What is the Treasury proposing to do?

The Treasury has a five-year plan. It says it will deal with public sector debt by increasing the Government's share of the "proceeds of growth" (the extra money generated by a growing economy) to 48 per cent, from the current 45 per cent level. All that is fine as long as tax revenues grow at the rate the Government is predicting. But some, including the influential IFS, are doubtful. The effects of the credit crunch are not over and are likely to depress corporation tax revenues, while Stamp Duty takings could also be hit by a misfiring housing market.

Any promising signs?

There are plenty of things working against Mr Darling at the moment. Though unemployment is down, this also lowers the potential for greater growth and consequent higher tax yields. Taking a tough stance on immigration blocks off another potential avenue of growth. And on Monday, a group of MPs warned the cost of operations in Afghanistan and Iraq would double to £3.297bn this year. But there is some good news. High oil prices boost Government coffers via corporate taxes. And though growth is likely to be around 2 per cent for 2008, predictions for 2009 are higher.

Should the Chancellor raise taxes to reduce government debt?

Yes...

* Some predict that the Treasury needs to raise an extra £9bn, so something should be done.

* We need to prepare for the worst – the effects of the credit crunch could still hit the economy.

* Without raising more in tax, the Treasury's self-imposed rules on forming a sound fiscal policy will be broken.

No...

* The public purse will be refilled when global economic conditions improve, so tax increases are unnecessary.

* Utility bills and food prices are up. The worst thing Alistair Darling could do would be to increase taxes.

* The Chancellor shouldn't raise taxes. He should lower them and kick-start the economy with some good old deficit spending.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments