State of disgrace: You can’t keep a bad man down

In the past, a disgraced politician would stay disgraced. Now the comeback is plotted even as the fall unfolds – and it shames us all

One way of seeing what happened to Anthony Weiner is that his life was turned upside-down by the push of a button. In 2011, when Weiner was a married expectant father and a congressman representing New York in the US House of Representatives, he was also engaged in an exchange of dirty messages with a 21-year-old student in Seattle. It was not, in the scheme of the universe or even of political scandals, a particularly big deal in itself. But when Weiner tried to send this student a picture of his crotch and instead distributed it to his 50,000 Twitter followers, and ultimately many others, it captured America’s imagination.

Later, in an interview with The New York Times, Weiner tried to lay out the reasons why. “My last name,” he began ruefully – headlines included “Hide the Weiner”, “Weiner’s exposed”, “Weiner won’t pull out”; “the fact that there were pictures involved; the fact that it was a slow news period; the fact that I was an idiot about it”. And all of these points are true. In the circumstances, it is perhaps unsurprising that he tried to cover it up.

Weiner was so desperate to keep his digital infidelity from the public and his wife that he claimed his Twitter account had been compromised, and spent fully $43,000 engaging private investigators to track down the mythical hackers. As more photos emerged, he had to concede that he couldn’t “say with certitude” that it wasn’t his crotch in the picture. He had to admit to six such online relationships over three years, roughly the course of his marriage to Huma, who, as it turned out, was pregnant. And then, despite being by all accounts an exceptionally able congressman, he had to resign. His friend of 20 years and former room-mate Jon Stewart ripped him to shreds on The Daily Show. As he gave his final press conference, a heckler shouted, “Goodbye, pervert!” It was, all in all, easy to feel sorry for him.

There have been moments in Chris Huhne’s saga, too, when even the most merciless of his many judges might have felt a sliver of sympathy. Few people could have taken any satisfaction from the decision of some newspapers to publish messages that detailed the awful impact on his family life. Many of us will be familiar with the lurching spiral of panic that accompanies a lie which seems small, and then metastasizes until the words coming out of your mouth seem to be out of your control. And again: he was, by most objective accounts, good at his job. We might regret that he had to lose it, for our sake as much as for his.

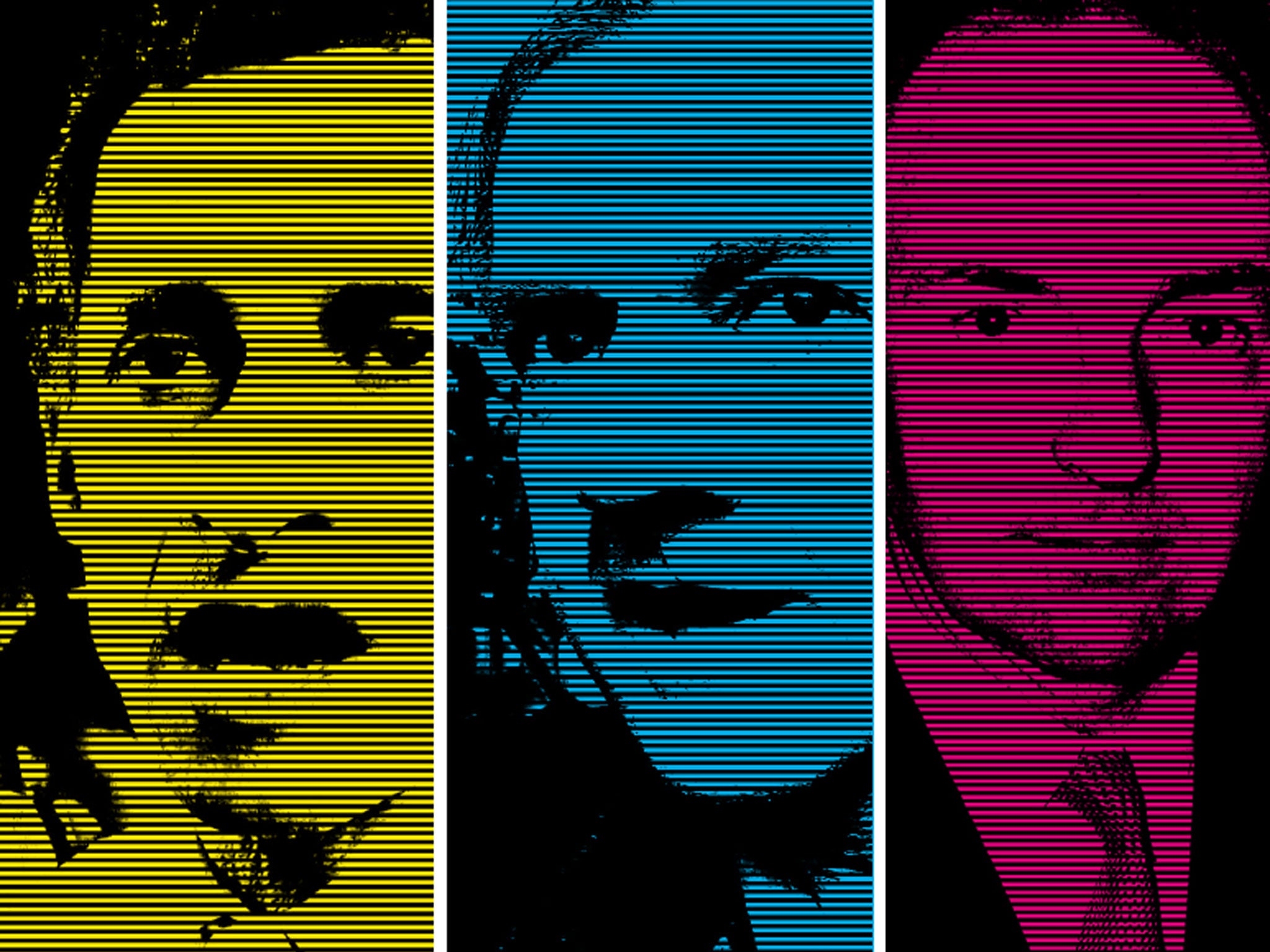

No one feels sorry for either of them now. Chris Huhne and Anthony Weiner are the poster boys of that dismal but increasingly commonplace phenomenon: the unearned political comeback. Their growth has been unmistakable. Our prurience has increased, and yet so has our tolerance for sexual misdemeanour. Meanwhile, an ever-growing proportion of our activities are catalogued online, where they may ultimately be found by enterprising enemies. The media on both sides of the Atlantic has become more ruthless. And more of our legislators than ever before are lifers with no hinterland to which to return. All of those factors have helped to create a political ecosystem that is more about your narrative’s chance of survival in competition than it is about telling or discerning the truth. And this makes it more likely than ever before that a disgraced politician’s first thought upon admitting wrongdoing will be: how do I get back to the top?

Start with Huhne, whose 62 days in prison does not seem an unduly draconian sentence for perverting the course of justice. He got out in May and last week, four months later, he made his first significant public contribution since then, in the debut of a weekly column he will be writing in The Guardian. He insists that he has no further political ambitions, but it has to be said that there are ways of keeping a lower profile.

In the piece that would have been more widely read than any other he will write, he could have put down a marker about anything he wanted. He could have declared his determination to carry on his ministerial work on climate change from outside Westminster, or devoted himself to penal reform, or road safety, or even the preservation of marriage. Or he could quite reasonably have decided that he’d had enough of all that, and treated us to a jolly slice of life chez Trimingham-Huhne, perhaps detailing a recent road trip.

He did none of those things. Instead, under the flimsy disclaimer that he realised it was all his own fault – a protestation that becomes less convincing the more often it is uttered – he used his platform for the noble purpose of blaming his downfall on a Murdochite conspiracy. Huhne’s suggestion is as follows: the media’s interest in his extramarital affair and criminal lies was not so much sparked by the same whiff of scandal that would make any politician a tempting target. Instead, they were the product of the world’s biggest press baron’s fears that the man who lost the Liberal Democrat leadership election to Nick Clegg was going to bring him down.

This isn’t about me, Chris Huhne would doubtless protest, as politicians so often do, but that seems psychologically dubious, at best; and, in all honesty, I find it difficult to give him the benefit of any remaining doubts. His appearances in the same vein on Newsnight and the Today programme, blissfully deaf to his own tone of entitlement, did little to restore that lost confidence. I understand that it’s my own fault, he kept on saying; except, he kept on implying, really it was Rupert Murdoch’s.

Not even Anthony Weiner could place responsibility at anyone else’s door for what happened to him when he decided to run for mayor of New York, although he darkly hinted at it on occasion, saying in one ad, for example, that “newspaper editors and other politicians” wished he would quit. (Newspaper editors, of course, were absolutely delighted at his persistence, Weinergate being the biggest gift of a story in anyone’s memory.) The second act of his downfall shades into a horrible sort of farce. It ended last week in his humbling primary defeat, with just 5 per cent of votes cast.

It is hard to say at precisely which moment he reached his nadir, but there is an extensive list of options, sadly too long to run through here. We will have to confine ourselves to the start and end of it: the moment when, as Weiner continued to explain how much he had learned and how sorry he was to Huma, a website called “The Dirty” revealed that he had sent another series of explicit messages to another young woman, one Sydney Leathers, more than a year after his resignation, and that indeed he had been involved in online relationships with two other women in the same time frame; and that he had done all of this under the irresistible pseudonym “Carlos Danger”. In other words, when he gave that repentant interview to The New York Times, he was still doing it.

And then, last week, his final humiliation: finishing the primary with just 5 per cent of the vote, Weiner arrived at his own election night party to find the aforementioned Ms Leathers, now a porn star boasting a boob job and a smartphone app to promote, waiting on the pavement, with the timelessly logical observation that “I’m kind of the reason he’s losing, so might as well show up”. Understandably keen to avoid such a meeting, Weiner and his entourage snuck in to his own wake through a neighbouring McDonald’s. Perhaps that process contributed to his state of mind when, a couple of hours later, he bombed out of the venue to his waiting car and gave the attendant press pack a heartfelt middle finger by way of farewell.

The day before, one incredulous television interviewer had asked Weiner the question that we civilians might long to put to both men: what is wrong with you? We might elaborate it as follows: anyone can make a mistake, of course, albeit that most of us manage to make mistakes that do not involve breaking the law or sending pictures of our genitalia to strangers. We may not even judge you on a moral basis. What you get up to in your private life is up to you. But having endured this maelstrom already, what would make you want to hurl yourself back into it, even when you must surely know that to do so is almost bound to end in humiliation?

As always, the two would argue that their motives are to do with selfless ideals of public service. But neither man is likely to amplify the issues with which he is allegedly concerned; Weiner acknowledged with priceless understatement that he is an “imperfect messenger”, and the truth is that having either of these two on your side is roughly as useful as getting a kitchen knife endorsement from a serial killer. To listen to Huhne’s interviews or Weiner’s stump speeches is to think: these are not points that must be made; these are voices that insist on being heard.

This is, of course, the problem with politics more generally: the qualities required to climb the greasy pole of public approval are not necessarily those that will really matter when you reach the top of it. And yet there are those seduced by power’s siren call who manage to resist it when it comes again. It is hard to think, for example, of a more admirable response to adversity than that of John Profumo, whose affair with Christine Keeler caused such a scandal in the early 1960s. Profumo’s first step after his resignation was not to plan the big comeback interview, or to start work on an autobiography; instead, it was to volunteer to clean the toilets at the anti-poverty charity Toynbee Hall. He worked there for the rest of his life, ending up as the organisation’s chief fundraiser. Eventually, he was awarded a CBE.

It is hard to see Chris Huhne, he of the personalised number plate, picking up a mop. It is hard, really, to see either man learning the lesson that Profumo grasped so modestly. They are creatures of power, peacocking alpha males whose whole sense of self relies on the approval of others. Their real tragedy has little to do with sexual appetite, or disregard for the law, or Rupert Murdoch: it is rooted in the fact that they need that approval quite so much. If they didn’t, we might imagine that one day they could win it back.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies