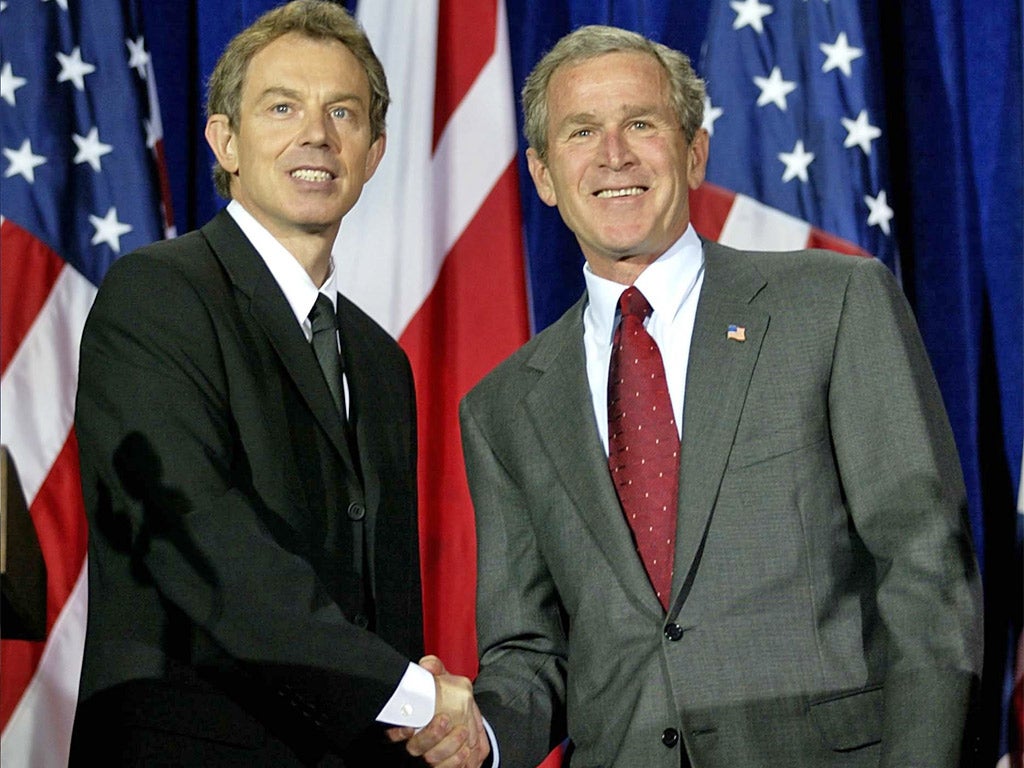

Spying on innocent British citizens by US intelligence was allowed by Tony Blair’s government - and still goes on

Leaked documents reveal a practice called 'contact chaining' was used to monitor British citizens with only a tangential link with a terrorist suspect

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tony Blair’s government gave America permission to store and analyse the email, mobile phone and internet records of potentially millions of innocent Britons. At the same time US security officials drew up plans to spy on British citizens unilaterally, without the knowledge of the UK government.

The revelations have emerged in leaked documents obtained by the National Security Agency (NSA) whistleblower Edward Snowden.

The documents reveal that in 2004 the UK allowed the US to store and target any UK landline numbers of people linked to a suspected person. In 2007 this was expanded to include mobiles, faxes, email and IP addresses. The deal meant that British citizens could be spied on even if they only had a tangential link with a terrorist suspect. US intelligence uses a practice called “contact chaining” – gathering data not just on surveillance target, but that of their friends and their friends, too. There is no evidence that the practice has been discontinued.

The documents, which have been seen by Channel 4 News and The Guardian, confirm for the first time that the American intelligence is able to spy on UK citizens who are not terror suspects. One, a January 2005 draft memo, was split into two different versions: one for sharing with US “five eyes” allies, including Britain, and one for US intelligence eyes only.

The version shared with Britain said the US could spy on British citizens “with the full knowledge and cooperation” of our government, and when it was “in the interests of both nations”.

But the version given to US intelligence staff said it “may be advisable and allowable to target… unilaterally when it is in the best interests of the US and necessary for US national security”. The memo makes clear the results would remain “NOFORN” – not for release even to British intelligence.

Another memo from 2007 sets out in more detail what kind of surveillance the NSA could and could not do.

It shows the NSA was still barred from making any UK citizen a target of surveillance that would look at the content of their communications without getting a warrant.

However, they were “authorised to unmask UK contact identifiers resulting from incidental collection”, “utilise the UK contact identifiers in Sigint development contact chaining analysis” and “retain unminimised UK contact identifiers incidentally collected under this authority within content and metadata stores”.

The document does not say whether the UK Liaison Office, which is operated by GCHQ, discussed this rule change with ministers in London before granting approval, nor who within the intelligence agencies would have been responsible for the decision.

A spokeswoman for the NSA declined to answer questions on whether the draft directive had been implemented and, if so, when. GCHQ also refused to comment.

The British Foreign Secretary in 2005 was Jack Straw, and in 2007 it was Margaret Beckett. When Channel 4 and The Guardian approached both to ask if they knew about or sanctioned a change in policy, they declined to comment.

France, Germany and Spain have all recently summoned their respective US ambassadors to discuss surveillance within their borders, while this month the UK ambassador to Germany was invited to discuss alleged eavesdropping from the UK embassy in Berlin.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments