Margaret Thatcher feared sex references in 1980s HIV campaign harmed nation's moral well-being

Archive documents reveal cabinet rows over public education programme

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The crisis created in Whitehall by the Aids epidemic led to an extraordinary row between Margaret Thatcher and her Cabinet colleagues over the dangers posed to the nation’s moral well-being by acknowledging the existence of anal sex.

The arrival of the illness in Britain in the early 1980s had persuaded ministers by 1986 that urgent action was needed to prevent the spread of HIV with an unprecedented public education campaign outlining its dangers and how to prevent infection.

With officials warning of up to 300,000 cases within seven years, the Conservative government was told it needed to issue clear advice on safe sex not only to those in the gay community but to the wider wider public as infections increased.

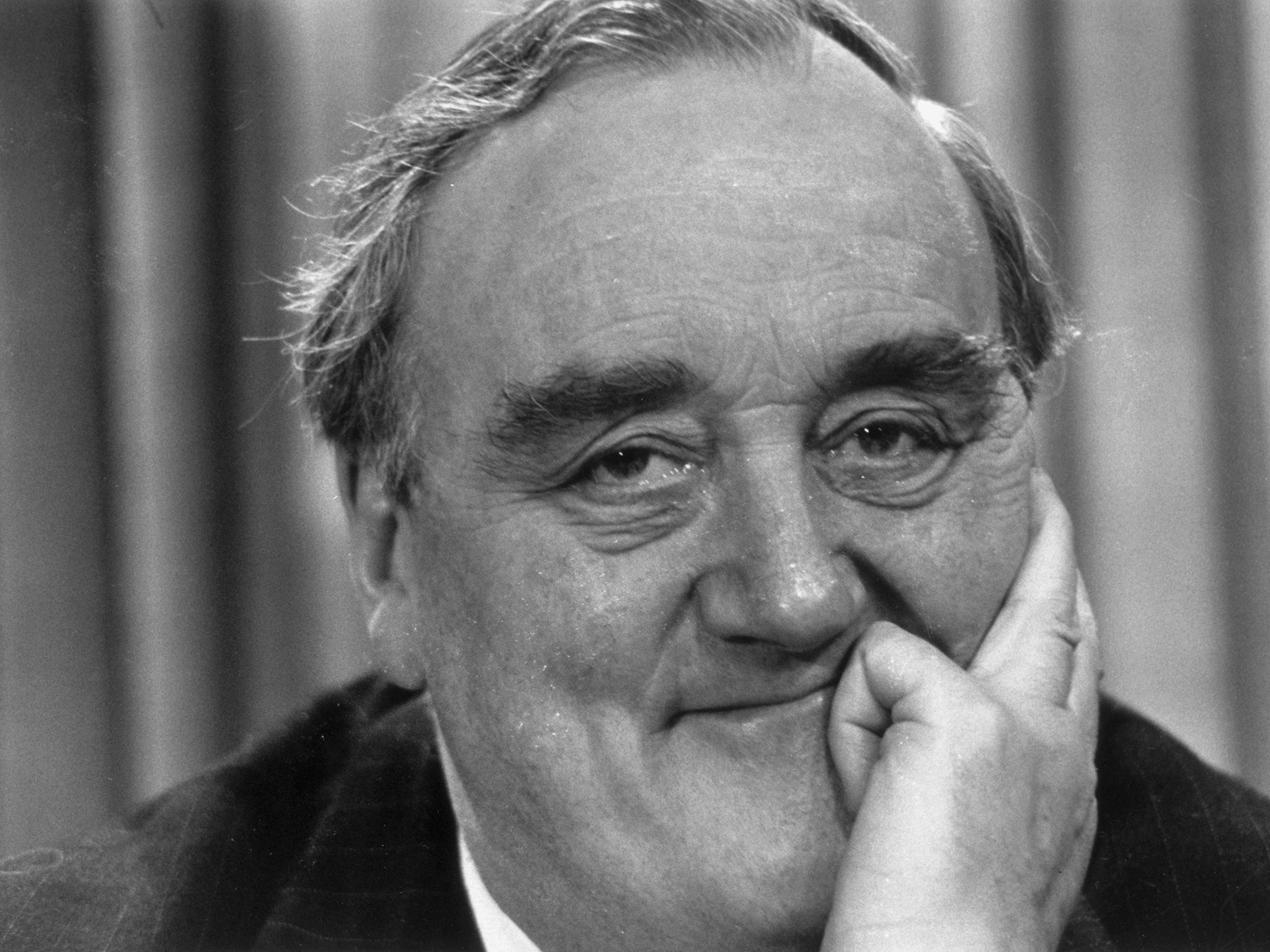

Documents released at the National Archives in Kew, west London, show that Health Secretary Norman Fowler proposed in February 1986 to publish full-page adverts in national newspapers explaining under the heading “Risky Sex” that unprotected anal intercourse carried one of the highest risks of transmission.

The adverts, described by then Downing Street policy adviser David Willetts as “explicit and distasteful”, drew a strong response from the Prime Minister herself, who expressed concern that it risked corrupting public morals.

Writing on a memo describing the campaign, Mrs Thatcher wrote: “Do we have to have the section on risky sex? I should have thought it could do immense harm if young teenagers were to read it?”

The debate was taking place amid wider public anxiety and ignorance about the disease which gave rise to misapprehensions about its transmission and a surge in homophobia. James Anderton, the chief constable of Greater Manchester Police, referred to victims as “swirling about in a human cesspit of their own making”.

Mrs Thatcher sent her right hand man Willie Whitelaw, then leader of the House of Lords, to put her concerns to a Cabinet committee set up to deal with the crisis. The documents show that he was told by Donald Acheson, the chief medical officer, that the “risky sex” paragraph causing the Prime Minister concern was the most important part of the campaign.

Unpersuaded, Mrs Thatcher then asked for an investigation into whether the adverts might breach the advertising code as well as the Obscenity Act.

When the answer came back that the campaign was legal, the Prime Minister responded: “I remain against certain parts of this advertisement. I think the anxiety on the part of parents and many teenagers who would never be in danger from Aids exceeds the good it may do.

“It would be better in my view to follow the ‘VD’ precedent of putting notices in surgeries, public lavatories etc. But adverts where every young person will read and learn of practices they never knew about will do harm.”

When Downing Street asked for the wording of the advert to be reconsidered, Sir Norman made it clear he felt the threat posed by the “grave and unprecedented problem” was not being adequately appreciated in Number 10.

He wrote to Mrs Thatcher: “Unless there is a reference to anal intercourse, which has been linked with 85 per cent of AIDS cases so far, the advertisement would lose all its medical authority and credibility.

“No one is condoning these practices - quite the contrary; but they exist and are one of the ways by which AIDS spreads - the spread into the population at large will accelerate.”

Underlining the urgency of the situation, Sir Norman added: “We cannot now decline to advertise about this serious disease. To do so would be to jeopardise the public health unnecessarily, and there would be many who would bring that charge home.”

The documents show that Mrs Thatcher’s concern at the direct nature of the public education campaign paled alongside the robustly Victorian views of her Cabinet colleague, Lord Hailsham, who wrote complaining at the colloquial use of the word “sex”.

The peer, who was serving as Lord Chancellor, said: “I am convinced that there must be some limit to vulgarity and iliteracy. ‘Sex’ means that you are either male or female. It does not mean the same thing as sexual practices. Nor does ‘having sex’ mean anything at all.

“Could they not use the literate ‘sexual intercourse’? If that is thought to be too narrow then why not ‘sexual relations’ or ‘physical sexual practices’, but not ‘sex’, or still worse, ‘having sex’!!!”

The row ended when health officials suggested that the phrase “anal sex” be replaced with “rectal intercourse” and Mrs Thatcher, perhaps beginning to be persuaded of the scale of the emergency, declared the new language acceptable.

Despite a warning that she was being seen as “reluctant to treat the issue with the seriousness it deserves”, the Prime Minister continued to be less than enthusiastic about the publicity campaign.

A series of leaflets and television adverts, famously showing a tombstone etched with the words “Don’t die of ignorance”, nonetheless followed.

Although criticised at the time for scaremongering, the campaign was later recognised to have been one of the most successful in the world and limited HIV infections in Britain to around the half the level of other European countries. It was widely imitated around the world.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments