Making of Labour's manifesto: 184 opinions – and endless meetings

It will take only a few hours for the political parties to present their manifestos, and for the political analysts to digest their contents this morning. None will be a great work of political literature. The prose will be bland, the promises vague – and yet, behind every word lies months of agonised thought, time consuming meetings, and political power-broking.

One of the issues leading politicians fight over – though not in public – is what a manifesto is for. Should it be long and detailed, or short and vague? Is it election literature, produced to attract votes, or a battle plan to be followed in the event of victory?

Labour's National Policy Forum was created by Tony Blair to involve enough party members in the process to make it seem democratic, without letting it slip out of the leader's control. The NPF is far too big to decide anything. It has 184 members, including 55 elected representatives of constituency parties, a minimum of 30 trade union officials, and 23 MPs or MEPs.

The NPF is broken down into five or six policy commissions. The most important commission, which thrashed out economic policy, was headed by the Chancellor Alistair Darling, and Cath Speight, chief equalities officer for the Unite union.

The documents which these commissions draw go up go to the NPF for approval, and are agreed by the Labour Party conference, and poured into the mix that becomes the party manifesto. This process came to a head last Thursday, when 70 or 80 Cabinet ministers, MPs, union leaders, researchers and others packed into Church House, near Westminster Abbey for the ritual 'Clause 5' meeting.

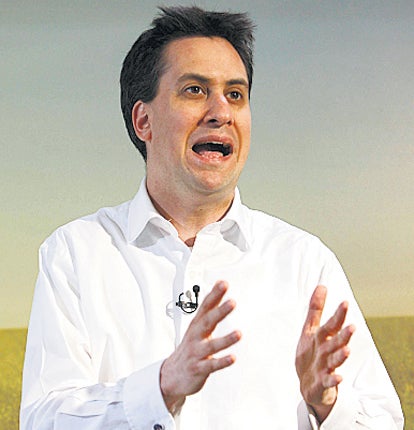

The meeting's title refers to an entry in the rule book which lays down that the manifesto must be agreed by a joint meeting of the Cabinet and the party's National Executive committee, plus the heads of the big unions and others on the invitation list. They sat at tables fanning out diagonally from the head table where Gordon Brown sat, flanked by Ed Miliband and Harriet Harman.

One participant in this process said: "Asking how the manifesto is written is like asking the Schleswig-Holstein question: only three people ever knew the answer, and one of them is dead. They kill us with kindness. There are long, long meetings and a mountain of paper, and reports which are very useful for sorting out wobbly tables, and you can get a word changed here or there, but you cannot challenge the principles. Gordon controls it all." The idea of short, tightly controlled manifestoes with minimal policy detail is not fashionable over at Conservative headquarters. In 2005, they offered an almost policy-free manifesto, running to just 7,000 words, their shortest since 1966. They lost, just as they had in 1966.

The brains behind the document to be presented today is Oliver Letwin, the former shadow Chancellor. He is 10 years older than David Cameron, but shares a similar background and has similar views on the need to modernise.

When the party leadership became vacant, in 2005, Letwin was one of the first to encourage Cameron to run, and he sketched out a scheme for opening up the whole process of policy making. It was more public than Labour's – though not necessarily any more democratic. There were 18 months of "open" policy reviews, which produced over a dozen shadow Cabinet green papers covering every important political topic.

Outsiders were encouraged to take part. The young billionaire Zac Goldsmith, who joined the party only in 2005, was made deputy chairman of the Quality of Life commission – as an indication that Cameron wanted people to believe they could vote blue and get green.

Not all the ideas churned out by these commissions have made it to the manifesto the Conservatives will publish today. Some, such as Zac Goldsmith's proposal for parking charges in out-of-town supermarkets, were ruled obvious vote losers. The rest were taken over by Letwin and James O'Shaughnessy, the head of research.

As an intellectual, Letwin tends towards the Bennite view of what the manifesto process is for. He thinks of it as a "blueprint for government," a means of ensuring Cabinet ministers are not overwhelmed or taken by surprise as they enter office for the first time.

But with an election approaching, the whole process threatened to be overwhelmed by the immediate need to set the political agenda with unexpected policy announcements that would put the government on the defensive, such as George Osborne's promise to cancel the proposed rise in national insurance. There is also a powerful political argument for keeping the Tories' intentions vague, because too much detail about how they plan to cut public spending could frighten the voters. The document that emerges may therefore be less detailed that Mr Letwin would have liked.

The other political parties do not have to agonise over how much to tell the voters about their real intentions. Their task is to put together a document that makes them sound like serious players, and with enough firm commitments to keep their supporters motivated.

The Liberal Democrats set up a nine-member manifesto working group in summer 2008 headed by Nick Clegg's chief of staff, the Inverness MP Danny Alexander. They met about once a month for the next 18 months, drawing up papers which were presented for approval to the shadow Cabinet and the Federal policy Committee.

But, as with the other people's, the person who controls the final content of the manifesto is the leader, Nick Clegg. He chaired the meeting of the Federal Policy Committee which finally approved its content, on 30 March.

The Green Party, believing in grass-roots democracy, tries to do things a little differently. This time, they set up a website and invited suggestions from party members as to what should be in the manifesto. Professor Andy Dobson, a political scientist at the University of Keele, wrote the first draft a year ago, in case there was an early election. Last autumn it was taken out and dusted down, by Caroline Lucas and various senior party figures. The final version was approved by the party's Regional Council which met in Oxford on January 23. It will be published on Thursday.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments