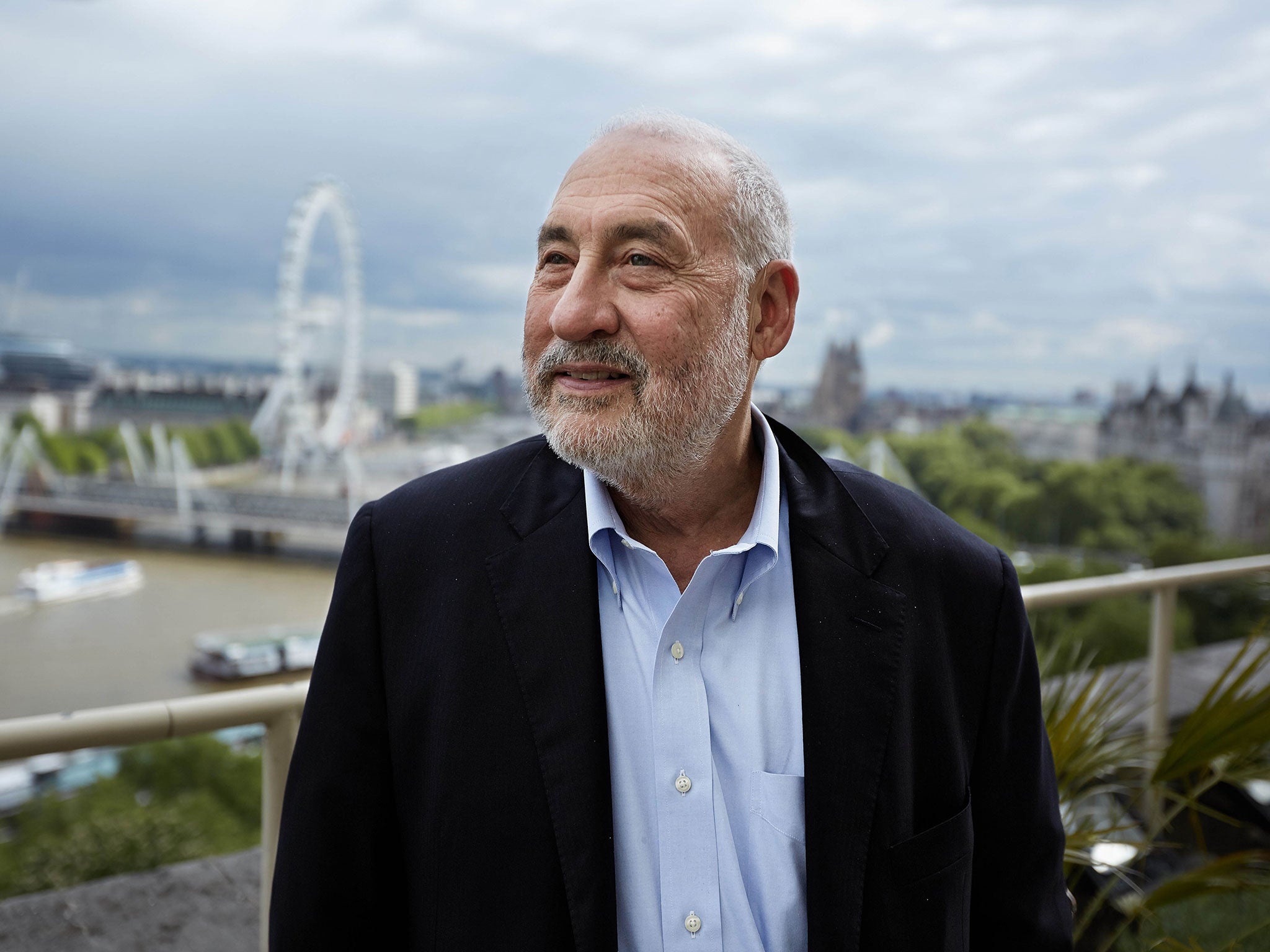

Joseph Stiglitz interview: Nobel-prize winning economist on advising Scotland on its future

His latest collection of writings puts inequality down to poor political policy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is the intellectual puzzle that draws Joseph Stiglitz back to inequality time and again.

And the more that is written about the gap between the world’s haves and have-nots, the wider it seems to get.

“Obviously, I would prefer it to be getting better rather than worse,” the Nobel Prize-winning economist says. “I guess what is depressing is that we have become so slow to recognise it and to begin to put in place policies that might address it even as evidence has accumulated.”

That evidence is striking. In the US, the top 1 per cent takes nearly a quarter of the nation’s income, while the average wage of male high-school leavers has slid by 12 per cent in 25 years. Chief executive remuneration has soared since the financial crisis in absolute terms, but also as a multiple of the average worker’s earnings.

In The Great Divide, his latest collection of writings, Stiglitz puts inequality down to poor political policy, not merely the way of the world. He identifies the Ronald Reagan era, 35 years ago, as a turning point.

“If somebody had said, I have a deal for you: we are going to lower the tax rates at the top and deregulate, and the outcome a third of a century later is that 90 per cent of you are going to see no income increases, many will see decreases, the economy is going to grow slower than in the past but all the growth is going to go to the top 10 per cent. It is inconceivable that any democratic society would have voted for that package. But it was not sold that way.”

So if inequality is a choice, how come the Conservatives won out over Labour when it was Ed Miliband promising to tax the rich and hike the minimum wage? Part of it was personality, part of it was storytelling, Stiglitz says.

“The story of a well-functioning market economy is that not only does it create jobs but it also creates increases in income that are shared – and the British economy is not succeeding in a fundamental way,” he says, squat and smiling, tie off, pens and spectacles poking out of his shirt pocket as he rustles through a bag of Pret A Manger goodies that is his snatched lunch.

“Real wages have never declined over as long a period of time as they have. Real incomes have never done as badly. You would have thought that would have been an important message.”

It is a divide that shows up clearly in London, which houses more billionaires than any other city, who have been drawn in by favourable tax laws, benign political regimes and a rich mix of arts and culture.

“Some of these people are just using your rule of law to protect money they have stolen in other countries,” says Stiglitz, 72. “From a global point of view, you are aiding and abetting theft.”

The global super-rich have also inflated the property market to the detriment of others. He sees the same issue in New York, where a couple of towers have been bought by oligarchs but stand empty, “an option on American citizenship if things go bad in Russia”.

The good news Stiglitz sees is that inequality is rising up the agenda in the US. Los Angeles city council voted last week to increase its minimum wage from $9 (£5.81) an hour to $15 an hour by 2020. In addition, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio, elected in 2013 on an equality ticket, has just unveiled a plan to take 800,000 people out of poverty by lifting pay and building more-affordable housing.

It marries with his own manifesto to reduce inequality and grow the middle class with subsidised childcare for millions more children and higher taxes on wealthy individuals and corporations. Stiglitz advised President Clinton on economic matters and hopes some of his ideas will be incorporated into Hillary Clinton’s tilt at the White House.

“It is trying to give her an intellectual frame that says, this is not a matter of bashing Wall Street, this is really about reconstructing our economy where the financial sector has an important role but is doing what it is supposed to be doing,” says the man who thinks jailing bankers is the best way to curb market abuse. “This is not about the politics of envy, it is about the economics of trying to create a shared prosperity.”

He goes on: “A lot of people who are hoping to support Hillary are trying to convince her that she has to distance herself from Bill – that this is not the fifth Clinton-Obama term, but a new Democrat. It is tricky but it will be more successful if she says we did some things right and we also made mistakes, but they were honest mistakes and we have to learn from them.”

In his book, Stiglitz critiques Thomas Piketty, the French author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, who some might call the pretender to his crown. Piketty writes that the natural state of capitalism is high inequality which can only be overhauled by a new regime of global taxation.

“My view is we have created this inequality through our policies, and that if we reverse those policies we will reverse the trend toward greater inequality.”

Born to a schoolteacher mother and insurance salesman father, Stiglitz grew a social conscience long ago. He was raised in Gary, Indiana, a steel town that suffered from industrial decline and racial unrest. As a college student, he attended Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963.

“We didn’t realise how many people would show up and no one realised what a moving speech that would be. That moment has always stayed with me.”

An academic career that took him from Cambridge to Yale stepped up a gear when Stiglitz was transplanted to the White House as a member of Clinton’s council of economic advisers, which he later chaired. Even when he moved to the World Bank as chief economist he revelled in his outsider status in Washington, insisting he spoke up for the developing countries, not his new employer which lent to them.

It is a stance that won him fans in Asia and beyond. One of the articles in the book describing how Mauritius made available free education for all, has been downloaded a million times. Stiglitz returned to academia at Columbia University in 2000 but has remained in hot demand on the international stage.

He has advised Scotland on its economic future as well as debt-laden Greece, which he thinks has a “50-50 chance” of dropping out of the eurozone as it once again comes close to running out of money.

“What disturbs me is that Germany and others have sold it as a complete failure,” he says. Stiglitz praises Greece for cutting back its expenditure in an austerity drive enforced by the European Central Bank, a flavour of medicine that was “designed to kill the economy” which has shrunk by a quarter.

He says that the ECB’s economic forecasts for Greece were wrong in 2010 and most subsequent years, adding: “If they had been my students and they came in with a series of models like that they would have got a D-minus or an F.”

He thinks Europe should change its stance and help Greece by recapitalising the banks to revive small-business lending in the nation.

And what of the UK’s future in Europe? Stiglitz is sceptical of David Cameron’s drive to secure reforms before a referendum on EU membership that is expected next year.

“I don’t think you can expect to negotiate different terms,” he says. “If the UK does it, why not France or Italy? Everyone has distinct circumstances. One of the basic principles when you join a club is if everyone takes exception to everything then you don’t have a club.”

Joseph Stiglitz: Biography

Education: Studied at Amherst College, Massachusetts (BA) and then completed a PhD in economics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1967.

Career so far: Cambridge University research fellow and then later academic postings at Yale, Stanford, Oxford University and Princeton. Chairman of Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers from 1995; chief economist at the World Bank from 1997. Co-founded the Initiative for Policy Dialogue, a non-profit organisation to aid democracy in developing countries, in 2000. Won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2001. Professor at Columbia University.

Personal: Married to his third wife, Anya Schiffrin, a former Wall Street Journal journalist who works at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. He has four children and four grandchildren.

‘The Great Divide’ by Joseph Stiglitz is published by Allen Lane

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments