Jeremy Corbyn to 'bring back Clause IV': Contender pledges to bury New Labour with commitment to public ownership of industry

Exclusive: Frontrunner pledges to bury New Labour, as all the deputy candidates confirm that they would serve under him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

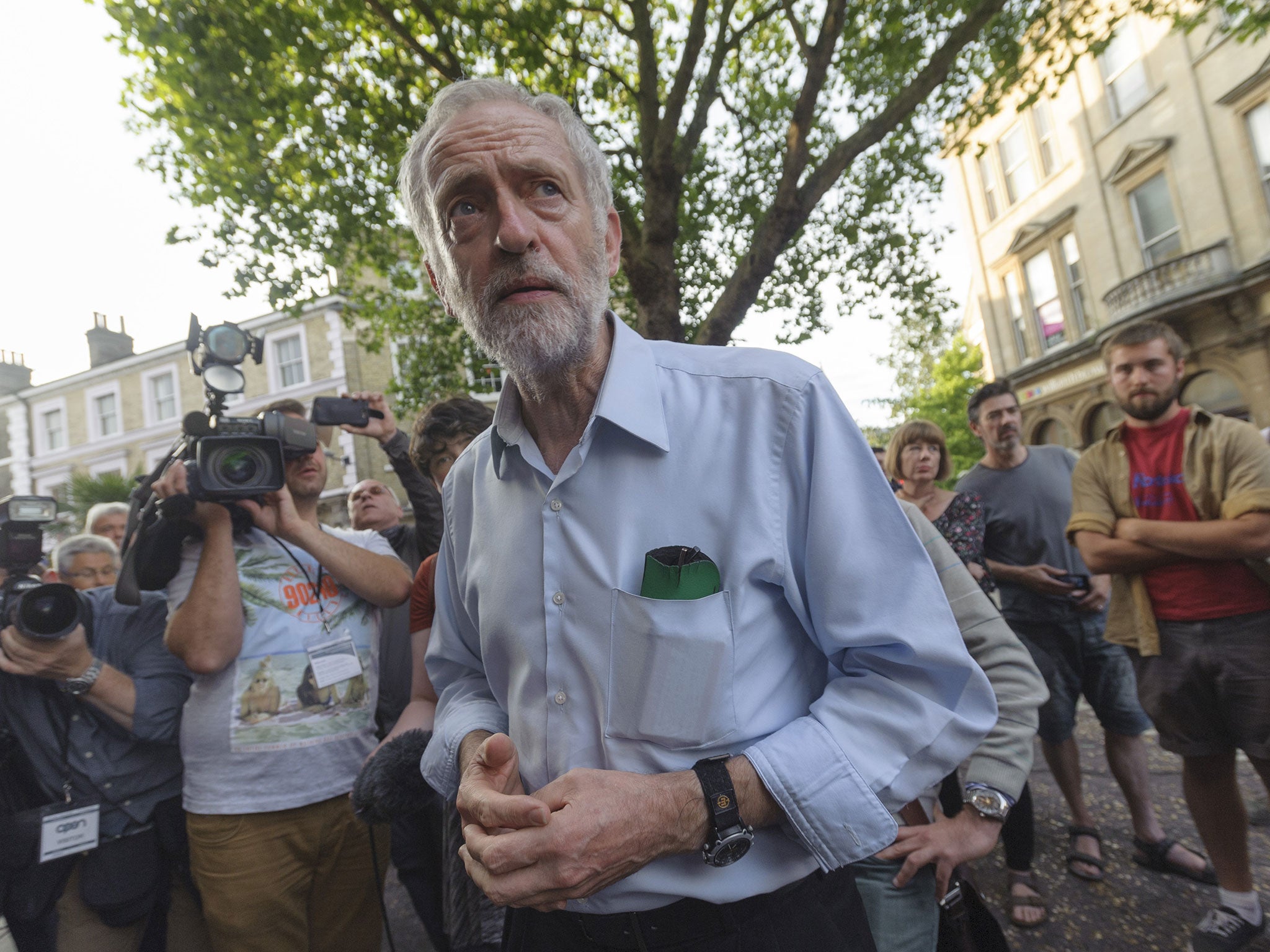

Your support makes all the difference.Jeremy Corbyn has risked provoking a damaging row at the heart of the Labour Party by pledging to restore Clause Four if he is elected leader next month.

In an interview with The Independent on Sunday, the man who has set alight the leadership race says the party needs to reinstate a clear commitment to public ownership of industry in a move which would reverse one of the defining moments in Labour’s history.

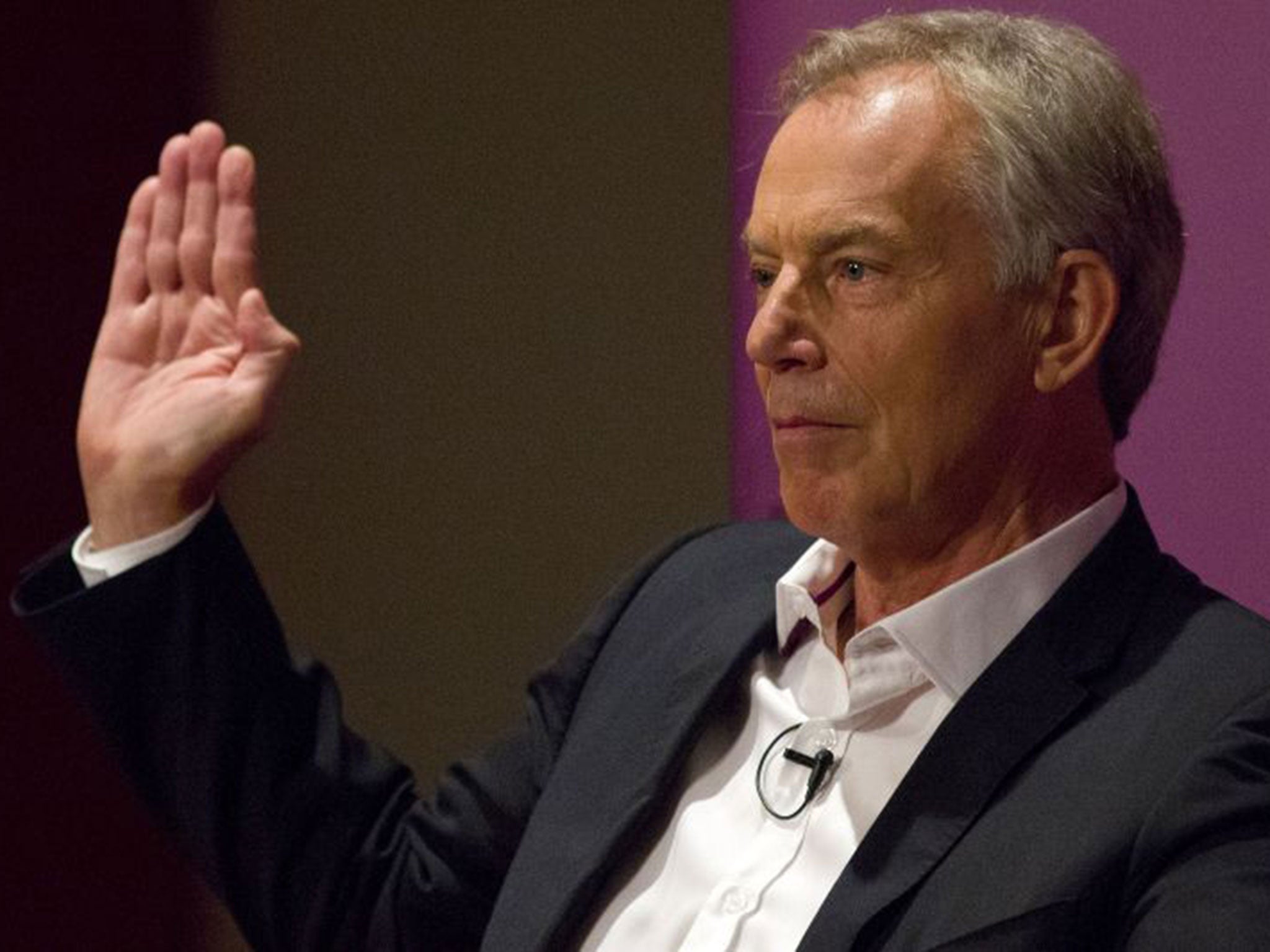

Mr Corbyn’s pledge will enrage many MPs and party members who see Tony Blair’s abolition of the old Clause Four two decades ago as a symbolic and essential move which recognised the importance of markets and made Labour electable.

However, the MP for Islington North, who believes he has captured a changing public mood, said voters, including the thousands who are signing up to Labour to vote for him, wanted to see a better return on public investment in railways and other infrastructure.

Asked if he wanted to restore the clause to the party’s constitution, Mr Corbyn said: “I think we should talk about what the objectives of the party are, whether that’s restoring Clause Four as it was originally written or it’s a different one. But we shouldn’t shy away from public participation, public investment in industry and public control of the railways.”

But his leadership rival Liz Kendall told the IoS: “This shows there is nothing new about Corbyn’s politics. It is just a throwback to the past, not the change we need for our party or our country. We are a party of the future not a preservation society.”

Jeremy Corbyn is sitting in a wooden hut in an urban nature reserve halfway through a press conference on his environmental policy. But as his supporter, the former MP Alan Simpson, fields a question about solar panels, the star candidate of the 2015 Labour leadership contest, in what appears to be a momentary lapse in concentration, puts his hand into his trouser pocket, pulls out a £5 note, stares at it with a look of surprise that is neither excited nor disappointed, and puts it back.

With six weeks to go in the most extraordinary Labour race in living memory, this fleeting moment captures the Corbyn demeanour: in this race, he’s just found a metaphorical fiver he didn’t know was there and doesn’t seem to know how to react. He doesn’t smile much, but neither does he get really angry. One can imagine him standing at the Despatch Box opposite David Cameron at PMQs in five weeks’ time and remaining infuriatingly calm and measured, while the Prime Minister grows ever redder in the face.

Despite the calm air around the MP for Islington North, he is about to cause a huge row in the party if he wins. In an interview with The Independent on Sunday, following the launch of his environment manifesto, Corbyn reveals that he wants to reinstate Clause Four, the hugely symbolic commitment to socialism scrapped under Tony Blair 20 years ago, in its original wording or a similar phrase that weds the Labour Party to public ownership of industry.

“I think we should talk about what the objectives of the party are, whether that’s restoring the Clause Four as it was originally written or it’s a different one, but I think we shouldn’t shy away from public participation, public investment in industry and public control of the railways.

“I’m interested in the idea that we have a more inclusive, clearer set of objectives. I would want us to have a set of objectives which does include public ownership of some necessary things such as rail.”

He also doesn’t rule out allowing the former Militant firebrand Derek Hatton back into the party that expelled him 30 years ago: “I think we’ve got to be open to bringing people back, but I’m not obsessed by it, I’m not that bothered by it … Many of the people who are supporting this campaign were born since the 1980s, they don’t even remember it because they weren’t around.”

Isn’t that the issue though, that those who remember the 1980s, particularly under Militant in Liverpool, don’t want the Labour Party to go back there?

Corbyn says: “We’re not going back anywhere, we’re going forward, we’re going forward in democracy, we’re going forward in participation, we’re going forward with ideas.”

Given that he has just said at his environmental launch that the leadership campaign has been the “most exciting period” of his life – “Whatever happens on 12 September, the cork is out the bottle, the candle is burning bright, the ideas are shining and there is a change in the air” – it is easy to see why he feels emboldened to make radical plans. But some of his fellow MPs are deeply uneasy about his links to the IRA, Hamas and Hezbollah, as well as what they warn will be the multi-billion-pound cost of “Corbynomics”.

And while there is excitement among the army of Corbyn supporters, the man himself carries the unassuming and slightly baffled air of Monty Python’s Brian who does not understand why people think he’s the Messiah. Or perhaps it is the Peter Sellers character Chance in the film Being There – the humble gardener who accidentally finds himself at the right hand of the US president and whose simple observations about the weather are seen as deeply philosophical commentaries on society. He doesn’t look or sound particularly dangerous.

When he arrives for the policy launch, at Camley Street nature reserve just behind King’s Cross station, Corbyn has to push his blue bike through a corridor of volunteers, photographers and TV cameras. He stops at a clearing, looks around and says to the crowd: “I hope Camley Street has got a bike lock somewhere.” It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that one of the avid supporters sees this as a stark critique of neoliberalism.

The eco-hub run by the London Wildlife Trust is packed with volunteers waiting to hear Corbyn speak. There is a hushed, reverential silence. Corbyn surveys the room and then, despite his humourless reputation, actually cracks a joke. After pausing for effect, the MP says: “It is traditional we start every event with a moment’s silence, for thought.”

During questions, a woman stands up and calls for a one-child policy to reduce the strain on the environment. It would be a gift to his opponents if he agreed with her, but he says: “I wouldn’t go down the route of the Chinese government, [which would be] brutal and cruel.”

Corbyn’s green policy proposals include giving communities greater powers to own local energy schemes, as they do in Germany, and he calls for “houses with gardens for everyone”, adding that “anyone who wants to be a beekeeper should be a beekeeper”.

In our interview, I say his opponents have a point in criticising his ideas as costly and utopian – and ask how he is going to deliver a house with a garden for everyone in Britain while protecting green-belt land?

“To give everyone a house and garden is very difficult in urban areas. But we can achieve something, and I’ve been involved with converting ground-floor car-parking spaces to growing areas on council estates in my area, giving people access to small growing areas. Children growing potatoes and tomatoes in their own soil is something they never forget.”

Corbyn has his own allotment in East Finchley, north London. He had been on the waiting list for years before a plot finally came up in March 2003 – the week the Iraq war broke out. He explains that it was the worst possible moment to inherit a plot because he was busy protesting against the US-led invasion, but took it on anyway, burning down derelict sheds that were there.

At the moment, he is growing potatoes, beans, soft fruit and apples: “I try to grow things that don’t require a lot of watering because I don’t get up there regularly enough. [But] I always make time for my allotment. You like a dry summer because the weeds don’t grow. You water what you need to water and the weeds can sod off.”

Blair's boast

Tony Blair described it as the “defining moment in the history of my party” when he successfully scrapped Clause Four in 1995, marking an end to nearly a century of Labour’s commitment to socialism.

The old Clause Four stated that the party was committed to “common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange”, but it was more than just a line of text. Mr Blair, who had been leader for less than a year, wanted to free Labour to embrace the market, and took on his party and the unions.

At a special conference in April 1995, Mr Blair successfully won the party’s agreement to sign up to a new Clause Four, which replaced the old wording with a commitment to a “dynamic economy, serving the public interest” with “a thriving private sector and high quality public services”.

On the issue of public ownership, the phrasing was changed to an economy “where those undertakings essential to the common good are either owned by the public or accountable to them”.

The change became totemic in Mr Blair’s transformation of Labour into an electable force post-Thatcher. It also became shorthand for how his successors could mark their place in history, with Ed Miliband, in particular, regularly urged to have a “Clause Four moment” which, in the end, never happened.

Jane Merrick