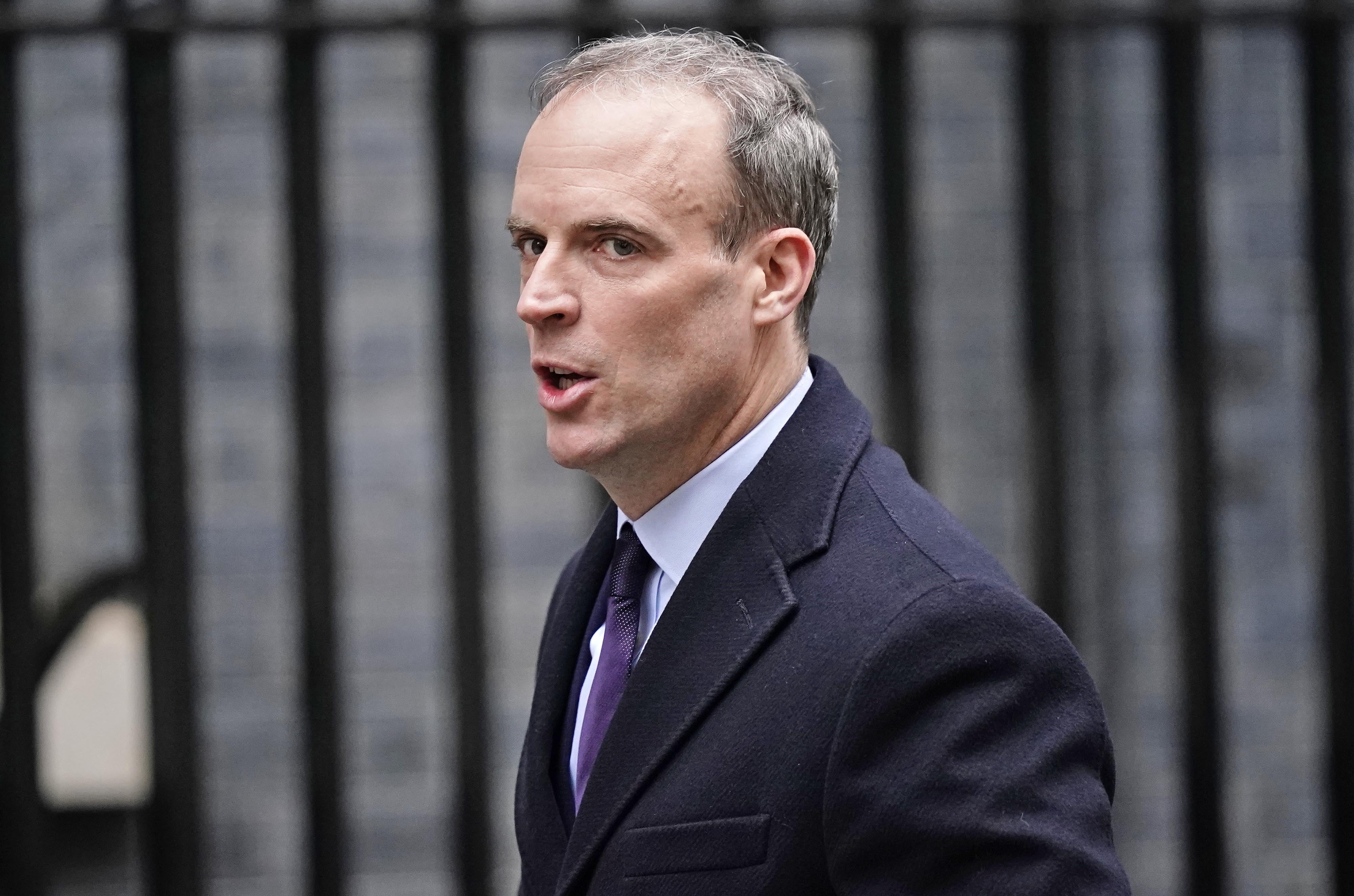

Dominic Raab’s ‘authoritarian’ overhaul will weaken human rights, MPs warn

Justice secretary calls for new ‘bill of rights’ after going against recommendations of government-commissioned review

Dominic Raab’s plan to overhaul the Human Rights Act is “authoritarian” and will weaken protections for ordinary citizens, MPs have warned.

The justice secretary has opened a public consultation to replace the law with a new “bill of rights”, which aims to stop foreign offenders asserting their rights to a family life to stop deportations.

The proposals go far beyond an official review commissioned by the Conservative government, which made several recommendations but concluded that “the Human Rights Act works well and has benefited many”.

It did not call for the law to be scrapped, and found there was an “overwhelming body of support for retaining” it.

But Mr Raab told the House of Commons that his proposals would uphold the European Convention of Human Rights and “prevent misuse and distortion”.

“We will replace section three of the Human Rights Act so that our courts are confined to judicial interpretation and are no longer – effectively, in practice – licensed by the act to amend or dilute the will of parliament expressed through statute,” he added.

Steve Reed, Labour’s shadow justice secretary, called the announcement a “dead cat distraction tactic by a government who do not know how to fix the criminal justice system that they have broken”.

“It is clearly not the Human Rights Act that is preventing foreign criminals from being deported; it is this incompetent Conservative government,” he added.

“These proposals do nothing to deal with the severe failings in the criminal justice system, they repatriate no powers that are not already based here.”

Labour MP Clive Lewis called the proposals “authoritarian”, as controversial bills that would criminalise protesters and asylum seekers go through parliament.

“Today’s statement does nothing to strengthen human rights and everything to weaken them,” he said.

“The Conservative Party is not a party of freedom, but one of growing authoritarianism.”

Fellow Labour MP Barry Sheerman questioned where the drive for the changes was coming from, adding: “I cannot find it supported in the academic community, the legal community or the business community, and it is increasingly clear that it comes from the increasingly strident right wing of the Conservative Party.”

Mr Raab said calls for reform “have come from our voters – the public”, but did not provide details.

Labour MP Andy Slaughter said the government had “picked on easy targets” by focusing on foreign national offenders, but the law would “mainly disadvantage ordinary citizens of this country who are victims of unlawful decisions by the state”.

Harriet Harman, chair of parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights, said previous Conservative pledges to overhaul the Human Rights Act had “ended up amounting to nothing”.

“We shall see whether he is able to turn his concerns into anything of substance,” she told MPs.

The government consultation claims that law-making powers have “shifted away from parliament towards the courts” and that “human rights inflation” has taken place.

It proposes changing the law so that “certain categories of individual” are not able to assert their rights to a family life to stop deportations, and that remedies for abuses will be affected by the “claimant’s conduct”.

Mr Raab said the change would “prevent serious criminals from relying on Article 8 and the right to family life to frustrate their deportation” in parliament, giving one example of a case dating back to 2008.

The government also wants to make people bringing claims under human rights law apply for permission from courts first, meaning that they must have suffered “significant disadvantage” or demonstrate an “overriding public importance”.

The consultation is asking for views on how to limit interference with the freedom of expression and formally recognise the right to trial by jury.

Legal experts questioned the reasons for the proposals, and how they would be implemented.

Barrister Schona Jolly QC said there was a “lack of evidence” to support the plans and that they could result in the UK losing more cases at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

“Arguments for asserting democratic control are heavily tainted by the government’s approach to repressive and regressive bills, and consistent attempts to bypass scrutiny and accountability in parliament,” she wrote on Twitter.

Human rights barrister Adam Wagner questioned how the proposals to restrict foreign offenders’ rights in deportation appeals could be lawful, writing: “Any statutory provision which takes away the rights of certain classes of individuals altogether would not survive a European Court of Human Rights challenge.”

The Independent Human Rights Act Review, which was commissioned by the justice secretary’s predecessor Robert Buckland last year, did not call for the major changes announced.

Chair Sir Peter Gross, a former Court of Appeal judge, said its recommendations aimed to improve how the Human Rights Act operates, rather than scrap or replace it.

“It is our view that the Human Rights Act works well and has benefited many,” he added.

The review made several recommendations, aiming to put UK law centre-stage and increase parliamentary scrutiny of court rulings, but said there was an “overwhelming body of support for retaining” the act.

“Detailed arguments in favour of repeal and replacement of the Human Rights Act with a British Bill of Rights were not provided,” added a document published on Tuesday.

Critics have said the review was politically motivated, following the government’s loss of numerous judicial reviews and immigration cases on human rights grounds.

In July, a separate parliamentary inquiry concluded that there was “absolutely no justification” for the government to change the Human Rights Act.

The Joint Committee on Human Rights said the existing law respected parliament and empowered British courts to enforce rights, rather than having to send cases to Strasbourg.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies