How Labour derailed the PM's Syria plan

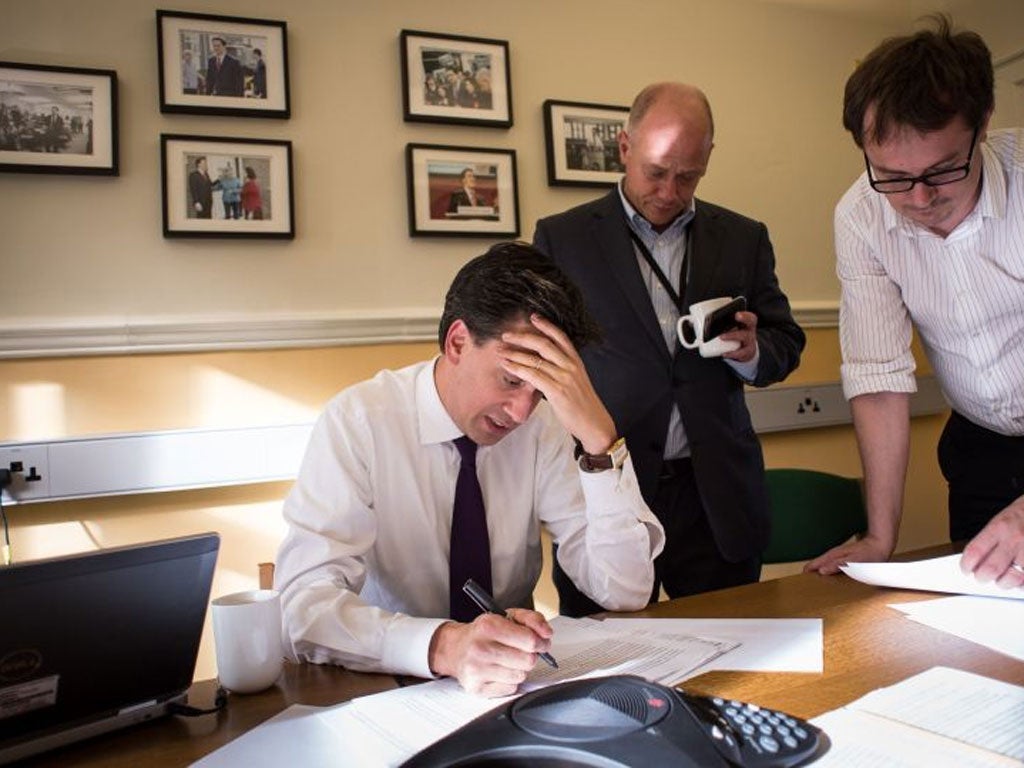

Opposition's insistence on 'evidence then decision' led to Commons defeat. James Cusick reports from behind closed doors

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The call was unexpected. The only thing David Cameron had been struggling with in Cornwall was sunburn – and the indignity of pulling on his beach shorts under a towel. But the 45-minute conversation with Barack Obama last Saturday put paid to the holiday mood.

The US President is said to have described his revulsion at the chemical weapons attack in eastern Damascus, and outlined the action the United States intended to take. Mr Cameron was given an assurance that US intelligence was solid and was told that the White House had already given up on the UN Security Council.

Mr Obama's military timetable will soon become clear enough. But the sequence of events following the call shows Mr Cameron believed he could deliver UK support.

The Foreign Secretary, William Hague, was contacted immediately after the President hung up. Mr Hague's office secured him a slot on the BBC Today programme on Monday morning, to begin preparing the public for the likelihood of military action. While he did not mention the recall of Parliament, by this stage the Speaker, John Bercow, had already been contacted about the possibility of bringing back the MPs.

On Tuesday morning the shadow Foreign Secretary, Douglas Alexander, used the Today programme to warn against the will of Parliament being ignored. Then at 12.36pm came confirmation – in the form of a tweet from Mr Cameron's personal account – that Britain was planning Syria action: "Speaker agrees my request to recall Parliament on Thurs. There'll be a clear Govt motion & vote on UK response to chemical weapons attacks."

Early on Tuesday afternoon, No 10 called the Opposition leader's office. A meeting was set up for 3pm. Ed Miliband and Mr Alexander joined Mr Cameron, Nick Clegg and Mr Hague in Downing Street. There, Mr Miliband and Mr Alexander had a list of questions about US evidence of the attack and the legal authority for action – and concerns about escalation. The exchanges were described as "robust", with Labour sources claiming Mr Cameron was "frankly dismissive" about the role of the UN, but saying there "can be a UN moment in New York". The meeting lasted 45 minutes, and closed on the understanding that the parties would talk again.

By this stage both Mr Miliband and Mr Cameron were feeling the growing concern of their MPs that the Commons wasn't going to roll over in a repeat performance of the Iraq debate in 2003.

Mr Miliband made two calls to No 10 on Tuesday night. The first focused on the UN weapons inspectors and why Parliament needed evidence first. The second, on the Security Council. Mr Cameron listened, but said little.

Another tweet from Mr Cameron at 10.05am on Wednesday morning explained the silence – the PM had submitted a draft resolution to the Security Council, seeking backing for "all necessary measures to protect civilians" in Syria.

Among Labour's leaders, there was puzzlement: why was No 10 doing this ahead of the inspectors' report? One of the government tweets mentioned "Security Council involvement" – something Mr Cameron had not given priority to the night before.

On Wednesday afternoon, the UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon, pleaded for time. UN inspectors would take four days to report. Added time for analysis might also be required.

Another meeting was set up, with the same cast-list as before. Early on in the meeting, Mr Cameron presented Mr Miliband with his draft motion for the Commons debate on Thursday. There was no parliamentary subtlety in it, no assurances of a second Commons vote. Labour sources say Mr Cameron offered no hint of any evidence from Washington, asking only if Labour would support him.

Mr Miliband said there needed to be more than "a UN moment" and that Labour was concerned international law needed to be upheld. If the ghost of Iraq 2003 had been hanging around, this was the moment the Labour leader decided to banish it.

Mr Miliband and Mr Alexander left Downing Street in Mr Miliband's car. The mood was one of unease. Neither was convinced by what Mr Cameron was saying. A rapid survey of the Shadow Cabinet's views was taken and it was agreed Labour would table its own amendment.

It was drawn up quickly between 4pm and 5pm and it demanded the UN be given the time it needed and that when the evidence became clear, the Commons would have a second vote. The phrase "evidence then decision" was offered to journalists in a briefing.

At 5pm Mr Miliband called Mr Cameron and offered detail on the amendment that challenged the Government. Their exchange was described as heated and uncomfortable. Mr Cameron accused Labour of "letting down America" – an indication that Downing Street had been working to Mr Obama's timetable, not Westminster's. He also accused Mr Miliband of "siding with Lavrov", the Russian Foreign Minister.

Within two hours of the call, at 7.05pm, the Government published a revised motion for a subsequent vote in the Commons on Thursday.

According to Conservative sources, the coalition Whips had already warned there could be difficulties. They were right.

Leaders flex muscles with reshuffles

David Cameron and Ed Miliband are preparing to reshuffle their top teams this month as both leaders attempt to reassert their authority over their parties.

Although Justine Greening, the International Development Secretary and one of four women in the cabinet, missed the Syria vote, No 10 has insisted that the PM accepted she had made a mistake. However, she could be moved sideways. But Education minister Liz Truss could join the Cabinet.

Labour's Rachel Reeves, Luciana Berger and Liz Kendall are also tipped for promotion. Mr Miliband's stance on Syria angered Blairite MPs, while he urgently needs to quell debate about his leadership.

Jane Merrick

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments