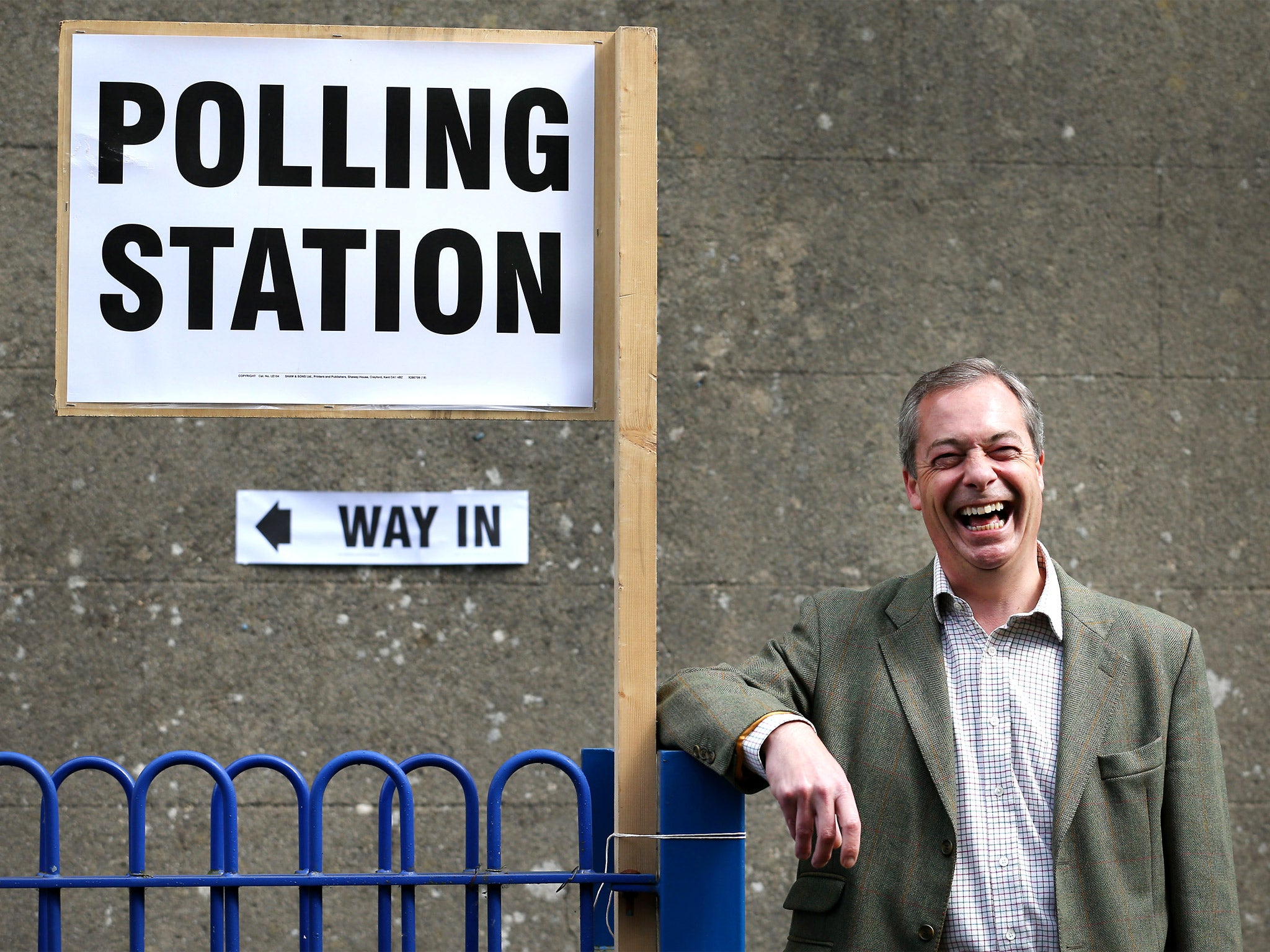

Has Ukip's success in the European elections proved that democracy is a flawed way to choose a government?

The popular vote has been criticised by people from Plato to Winston Churchill. So has Ukip's victory proved them right?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In its Person of the Year issue for 2006, Time magazine put "you" on the cover along with a reflective screen. Editors looking for a way to cover this week's European elections, which saw populist parties sweeping to power across Europe, might be tempted to repeat the conceit.

There are lots of reasons for popular discontent at the moment. The European Union is run by technocrats who are more interested in Cartesian logic than in popular opinion. The European Parliament is a dysfunctional institution which spends half its life in transit between Luxembourg and Strasbourg, and does not deign to demand receipts for MPs' expenses. And the past five years have seen the worst economic crisis since the 1930s, a crisis that has stoked up popular anger with elites of all varieties, from bankers to Eurocrats.

But "you"– the men and women reading this article and grumbling about broken politics – cannot escape some of the blame for the current crisis. You have maxed out your credit cards and thrown away the bill. You have voted for unaffordable social programmes. You have called for more spending and lower taxes. You have ignored the politicians who call for a return to responsibility (Jean-Claude Juncker, the former Prime Minister of Luxembourg, who is in the running to become the head of the European Commission, likes to quip of his fellow politicians that "we all know what to do; we just don't know how to get elected if we do it"). And you have behaved just as irresponsibly, in last week's election, as you did in the ones before that.

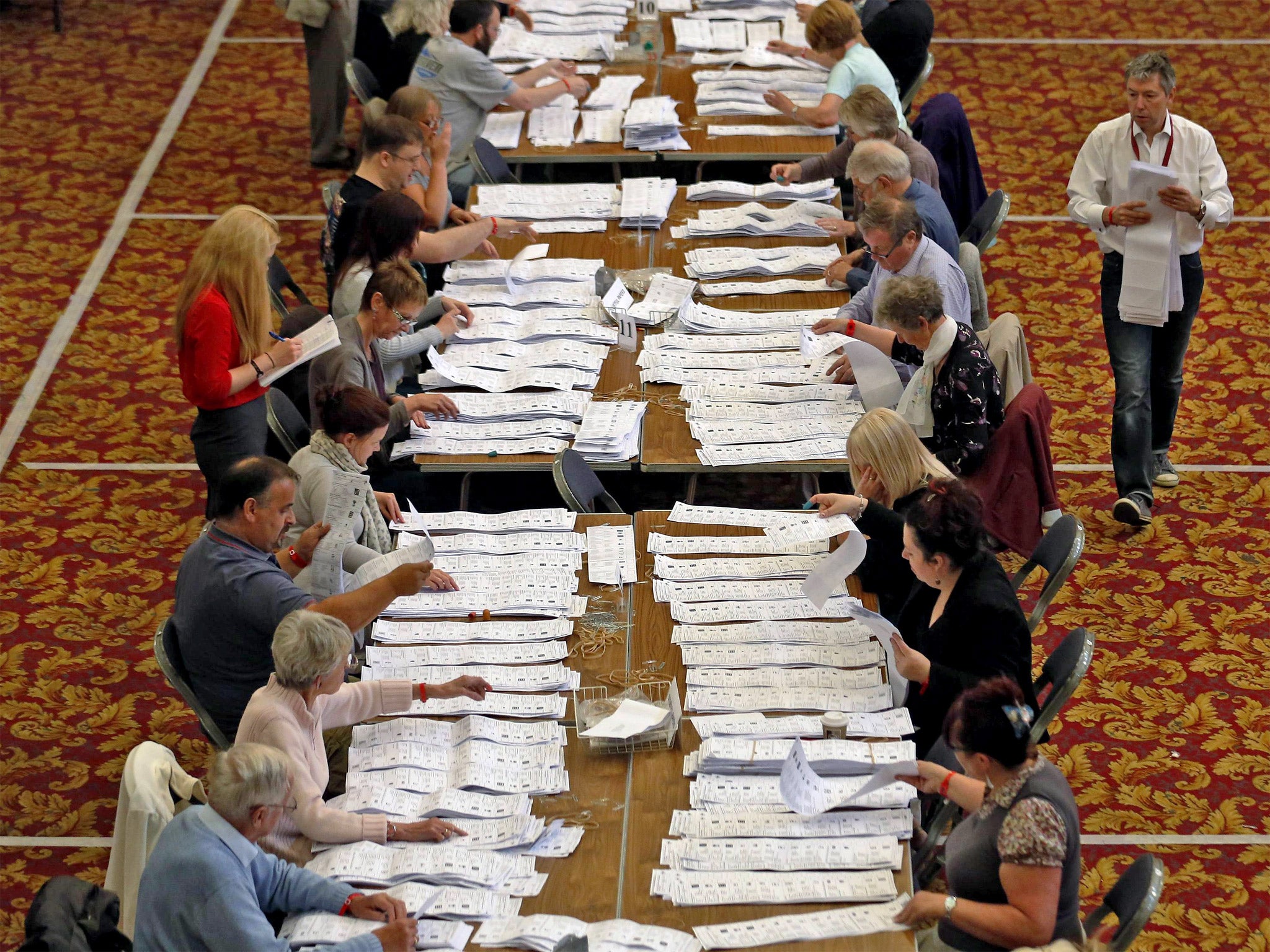

The mood of the European electorate at the moment is a strange mixture of anger and apathy. Millions of Europeans are furious enough with the European project to vote for once-marginal parties – most worryingly the French Front National (which attracted 25 per cent of voters) but also Britain's UK Independence Party (Ukip), the Danish People's Party and the far-left Syriza in Greece. But even more people could not be bothered to vote at all. The angry and the apathetic both have one surprising thing in common: they don't really expect that much to change any time soon. The populists would rather rail against the system than reform it. Nigel Farage's Ukippers believe that the European Union is so misguided that the only way to deal with it is to leave it. The non-voters believe that nothing that they can do will make any difference.

You can find exactly the same distemper in the United States – indeed, Europe's populist parties are in many ways the US Tea Party in a new guise. Next November's congressional elections will be a repeat of the European elections: thousands of people will trudge to the polling booths in order to express their fury with Washington DC; thousands more will stay at home because they don't think that expressing their fury makes any difference.

Can anything be done about the problem of "you"? A growing number of people are beginning to conclude that the answer is: "Very little."

In The Republic, Plato worried that democracy meant the rule of the ignorant over the wise. It encourages people to "live from day to day, indulging the pleasure of the moment". It allows them to vote for contradictory things. He called democracy a "theatre-ocracy" with the vulgar hordes gawping at professional politicians on the stage and voting for the ones who produced the prettiest speeches and the juiciest promises. Today, it is hard to deny the force of his argument.

Democracies routinely neglect long-term investment in favour of short-term projects. In the West, the proportion of GDP that countries invest in infrastructure has fallen from 5 per cent in 1960 to 3 per cent today. In the East, China boasts gleaming airports and first-class motorways, while India holds its infrastructure together with sticking plasters. Democracies also routinely appease powerful interest groups to the detriment of the common weal. In Spain, a rigid labour market ensures that a quarter of the workforce is unemployed. In France, the government has caved in to popular pressure and kept the retirement age at 62, despite lengthening life expectancy.

Voters also want contradictory things. They want to enjoy the fruits of prosperity without any of the necessary sacrifices. They want to drive cars that don't break down. They want to be able to buy the latest iPad. They want to eat avocados every day. But they balk at all the practical measures that make this possible – World Trade Organisation rules that lower trade barriers, European Union rules that harmonise qualifications, and corporate strategies that allow companies to create global supply chains.

The Californian system of ballot initiatives, which gives citizens a direct say in both taxing and spending, provides a particularly vivid example of the problem. Californians have repeatedly used the power to vote for more spending (particularly on schools and prisons) and lower taxes (particularly on property). The result is a cascade of financial disasters. Cities such as San Bernardino, Stockton and Mammoth Lakes have been forced to declare bankruptcy and cut back on essential services (San Bernardino's city attorney advised residents to "lock their doors and load their guns because the city could no longer afford enough police").

Voters combine magical thinking with cynicism about politics. Membership in the mainstream national parties has collapsed, in Britain's case from 20 per cent of the voting-age population in the 1950s to just 1 per cent today. Political parties are finding it harder to win majorities: in 2012, only four of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's 34 countries had governments with absolute majorities in parliament. Such cynicism might be healthy if people wanted little from the government. But given that they continue to want a great deal, it produces a toxic mixture: dependency on government on the one hand, and disdain for government on the other.

So what can be done about the problem of "you"? Winston Churchill's quip about democracy being "the worst form of government apart from all the others that have been tried from time to time" is no less true for being overfamiliar. For all its manifold problems, democracy beats all the alternatives. One reason for this is that it gives people something that they value highly: the right to express their own opinions. The question of whether those opinions make sense is strictly secondary to the right of expressing them. This right allows people to let off steam (democracies are much less likely to be rocked by revolts than autocracies) and provides a constant feedback mechanism to the governing class.

The other reason is that democracies are self-correcting. Alexis de Tocqueville once drew a sharp contrast between democracies and autocracies: democracies look weak on the surface but are strong beneath; autocracies look strong on the surface but underneath are dangerously brittle.

There were a few signs of this self-correcting mechanism in the European elections last week. The traditionally dysfunctional Italy produced one of the most sensible results: voters ceased their flirtation with Beppe Grillo and his Five Star Movement, and voted overwhelmingly for Matteo Renzi, Italy's young Prime Minister. There were arguably signs in the Indian election the week before. Narendra Modi comes with a huge potential downside given his flirtation with anti-Muslim bigotry.

But he also comes with an upside: he is a man of action who wants to get India moving again, and the voters gave him the political majority he needs to fulfil his ambition. California has long been a textbook example of dysfunctional democracy, from its initiative process to its wildly partisan parties. But under Jerry Brown, its current Governor, the system is beginning to fix itself. The state is running a surplus. Primaries have been opened and redistricting handed to an independent commission. Mr Brown has summoned a Think Long Committee to look at the state's long-term problems. If California can fix itself, then so can almost anybody, including the European Union.

But it is not enough to wait for the system to fix itself. It is also sensible to adjust democratic systems to make sure that "you" are not allowed to create catastrophes. The founders of modern democracy, from America's founding fathers to great liberal thinkers such as Alexis de Tocqueville and John Stuart Mill, regarded democracy as a powerful but imperfect mechanism: something that needed to be designed carefully, in order to harness human creativity but also to check human perversity, and then kept in good working order. Today, people have come to take it for granted: they loathe their leaders and regard them as corrupt and inefficient but simply assume that democracy is a permanent feature of political life. It is time to save democracy from such complacency.

This means putting a great deal of effort into reforming the institutions of the European Union before more and more Europeans abandon them completely. Brussels needs to take its commitment to subsidiarity more seriously. The European Parliament needs to become more frugal. Europe more generally needs to refocus on smoothing the relationship between sovereign nation states rather than creating a United States of Europe.

Democracies in general need to do more to put their fiscal houses in order. Democracy may be the worst form of government apart from all the others. But over recent decades it has become sloppy and self-indulgent, overloaded with obligations and distorted by special interests. And it has become sloppy and self-indulgent at a time when the Chinese have produced an alternative model that is becoming increasingly attractive to people across the developing world from Beijing to Brasilia.

Democracies have always taken trouble to build in elaborate checks and balances to make sure that majorities cannot tyrannise over minorities or ride roughshod over individual rights. The United States created a Bill of Rights and a Supreme Court. It also divided powers between the executive and the legislature and the federal and state governments.

Sensible democracies are also experimenting with similar policies to stop politicians from bribing their electorates, and current voters from robbing future generations. Giving control of monetary policy to independent central banks reduced inflation rates in the West from 20 per cent or more in the 1980s to almost nothing today. Giving control of fiscal policy to independent commissions could help to bring entitlements under control. The Swedes have already done this: in the 1990s, they rescued their country from financial crisis in part by pledging to balance their budgets over the economic cycle and employing a group of senior politicians to produce a blueprint for a sustainable pension system. The Americans, alas, tried and failed. The (Alan) Simpson and (Erskine) Bowles commission – which included politicians from both parties and recommended reforming the tax code to reduce basic rates but also eliminate or cut various exemptions such as the mortgage-interest deduction – provided the best chance of restoring fiscal sanity in years. Let us hope its failure will spur further action in the future.

John Adams, America's second President, once said: "Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide." Adams's gloomy prognosis was happily proved wrong. Democracies have seen off their many rivals from the monarchies of Adams's own day to Soviet totalitarianism. But democracy is looking a little threadbare these days, particularly in Europe and America, its supposed home, and this is damaging the spread of democracy abroad, which once looked unstoppable but is now repeatedly running into the sand, from Egypt to India.

The solution to this problem is not to give up on democracy but to revive and retool it. This will take the form of tying our hands a little so that we cannot squander our children's inheritances. And it will take the form of making more efforts to reform institutions such as the ones in Brussels that have become self-indulgent and lazy. It is time for the people to stop railing at our collective institutions and start fixing them.

'The Fourth Revolution: The Global Race to Reinvent the State', by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge (Allen Lane, £20) is published today. To buy it for £16 (free P&P), call 0843 0600 030 or go to independentbooksdirect.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments