Government derailing of salt reduction programme 'put people at greater risk of heart disease and strokes,' says leading expert

Andrew Lansley’s decision to hand responsibility for monitoring salt reduction to the food industry was a 'major step backwards' for public health

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Coalition government derailed the UK’s hugely successful salt reduction programme, putting the public at a greater risk of heart disease and stroke, a leading expert has said.

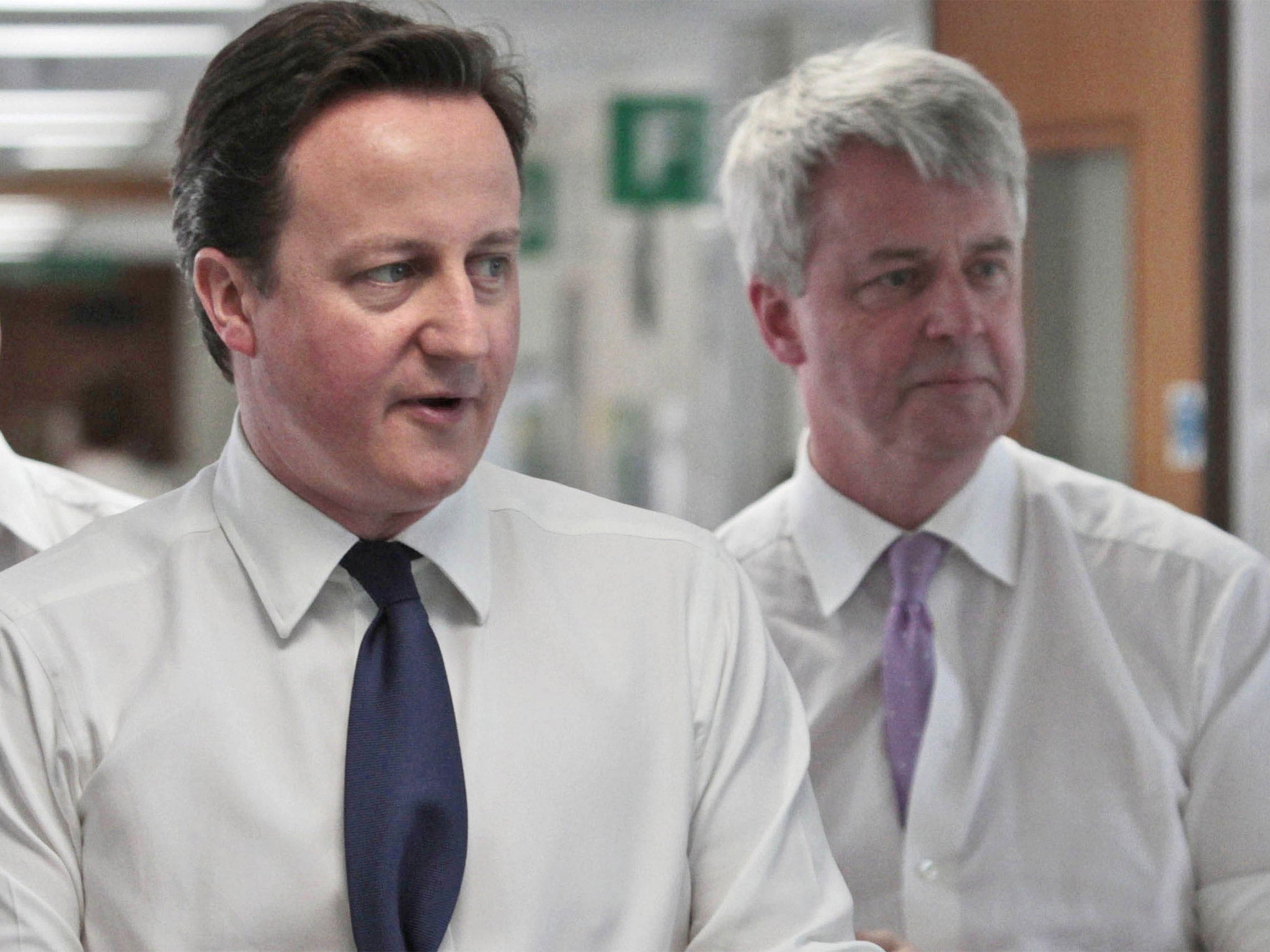

Professor Graham MacGregor, who helped spearhead the campaign to cut the amount of salt that manufacturers put in food, said that former Health Secretary Andrew Lansley’s decision to hand responsibility for monitoring salt reduction to the food industry had been a “major step backwards” for public health.

A drive to cut the nation’s salt intake began in 2006, when the Food Standards Agency (FSA) set targets for the industry, and set up robust monitoring of salt levels in British diets.

The strategy yielded impressive results, with average salt intake falling by 15 per cent between 2003 and 2011, a shift that was accompanied by a drop in heart disease and population rates of high blood pressure, preventing an estimated 9,000 deaths from heart disease and stroke annually.

However, writing in the BMJ alongside colleagues, MacGregor, who is professor of cardiovascular medicine at the Wolfson Institute of Preventative Medicine and chairs the influential campaign group Consensus Action on Salt and Health (CASH), said Mr Lansley’s arrival at the Department of Health heralded a significant change of course.

In 2011, Mr Lansley launched ‘Responsibility Deals’ with the food and alcohol industries, and moved responsibility for nutrition from the FSA to the Department of Health. The moves led to a number of key groups, including the British Heart Foundation and Diabetes UK withdrawing their backing for the Government’s plans.

The new deal relaxed monitoring of salt reduction, allowing the food industry to present their own feedback, Professor MacGregor said, while Mr Lansley also declined to set new salt reduction targets for 2014.

New targets for 2017 were eventually put in place by the new public health minister Anna Soubry, but four years of salt reduction were “lost”, Professor MacGregor writes, which might have cut salt intake by a further 0.9g a day, potentially saving 6,000 lives.

“Additionally,” he writes, “there has been very poor sign-up to the 2017 salt targets, with big companies such as Unilever, McDonalds, and Kellogg’s failing to publicly commit to the Responsibility Deal”.

A spokesman for the Conservatives said that through voluntary action with industry, the UK had been able to go “further and faster” on salt reduction than regulations would have allowed, highlighting that three quarters of the food retail market and 60 per cent of major high street restaurants had committed to further salt reduction.

However, Shirley Cramer, chief executive of the Royal Society for Public Health, said she also had concerns over the Responsibility Deals, adding that the next Government should consider tougher enforcement to guarantee action from the food industry.

“The time is ripe for a new Public Health White Paper and as part of this whoever forms the next Government needs to look again at the Responsibility Deal as it is not working as well as it could,” she said. “We feel that a revised model with common goals, clearer focus and greater incentives for sign up might make more traction. The Government should also consider enforcement action or disincentives for those that do not sign up.”

Some food manufacturers say that further reductions in salt content may be difficult without compromising safety, taste, texture and shelf-life.

Barbara Gallani, director of regulation, science and health at the Food and Drink Federation said increased Government funding would help companies “overcome shared barriers to further salt reductions”.

Official guidance: season with care

Adults should not eat more than 6g of salt a day – about a teaspoon. Babies should have no more than a gram, one- to three-year-olds 2g, four- to six-year-olds 3g, and seven- to 10-year-olds 5g.

In 2003, Britons took an average of 9.5g a day. Guidance by the FSA contributed to a decline in average daily intake to 8.1g by 2011. The salt content of bread fell by around 20 per cent. Under the Responsibility Deal, 60 per cent of the retailers and manufacturers committed to further cut salt levels.

Salt content varies between different food products and the NHS advises people to compare brands. Ready meals, pasta sauces, and pizzas are likely to be high in salt. Tesco’s Finest Wood Fired Margherita Pizza, for example, contains nearly two-thirds of the recommended daily intake, while Sainsbury’s Chicken Balti and Pilau Rice ready meal contains nearly half.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments