Donald Macintyre's Sketch: Mandarins put the ball back in PM’s court over Kids Company

The hearing has shed more light on the conflicting roles of permanent secretaries than on what we knew already

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Labour Public Accounts Committee chair Meg Hillier may not yet terrorise her witnesses with quite the cheerful grandstanding of her predecessor Margaret Hodge. But no one could accuse her of not getting to the point. This was not, Ms Hillier explained to the two top civil servants, about whether Kids Company did their job, but whether “you did your job”.

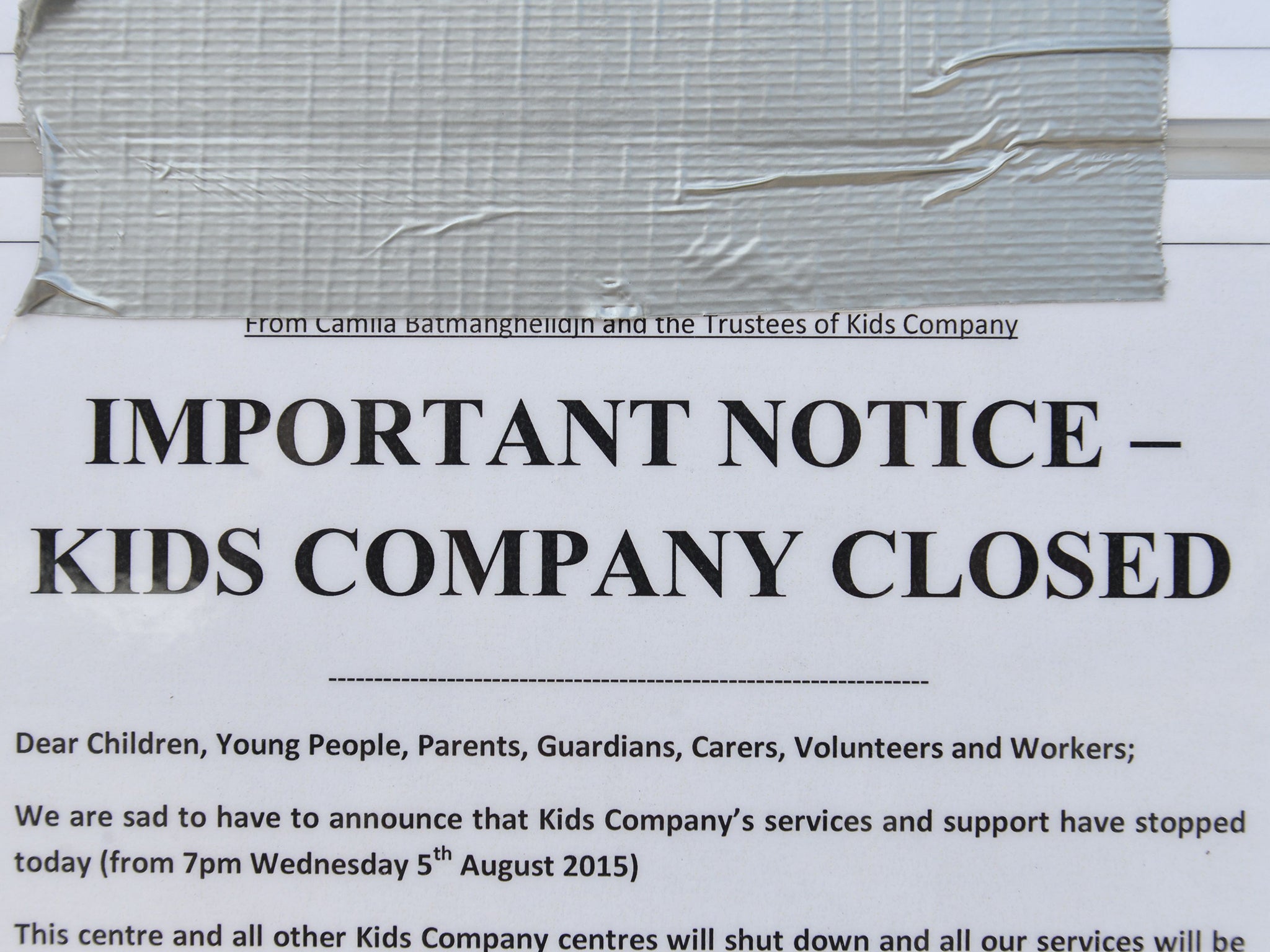

And so it was. The hearing shed more light on the uneasy relationship between the role of permanent secretaries as accounting officers and as servants of their ministerial masters, than it did on what we knew already — namely that Kids Company was, as Richard Heaton put it in a masterly mandarin’s understatement, “Prime Ministerially favoured”.

Department for Education Permanent Secretary Chris Wormald’s insistence that Kids Company did not receive “special treatment” was not helped by the fact that he tends to look slightly shifty even when he has nothing to hide. But it would have been difficult to sustain in the face of the 2013 decision to make it a hefty grant despite it having just lost a competitive bid for it. Mr Wormald had produced the “public interest” case that this was proper for ministers to do – including “reputational damage to their wider agenda” if they didn’t. Or as the day’s chief prosecutor, Tory David Mowat, put it more crisply, “PR”.

Much evidence was in Whitehallese. Repeatedly, Mr Wormald acknowledged there were “learning points” from the episode. Mr Heaton said one was that “evidence first and decision second is better than the other way round” – which Ms Hillier described sarcastically as a “revelation”.

It was therefore refreshingly blunt of Mr Heaton to say that when, in June this year, he finally advised against yet another £3m grant, minsters had “a punt” by giving the charity one last chance. The civil servants both insisted they did not come under political “pressure” to act as they did – or didn’t – before that point. But it became clearer by the minute that the politicians still have plenty of explaining to do.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments