Breakthrough in 'Cameron's war' – but No 10 fears rebel divisions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

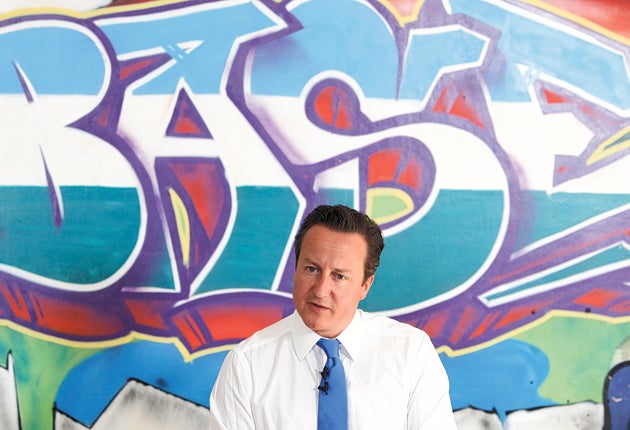

Your support makes all the difference.This time David Cameron didn't mind interrupting his holiday. Two weeks after cutting short his main summer break in Tuscany because of the riots, the Prime Minister broke another family holiday in Cornwall to handle Britain's response to the dramatic endgame in Libya.

After taking a high-stakes gamble by calling for international intervention six months ago, Mr Cameron could hardly be blamed for wanting a share of the limelight when Muammar Gaddafi's regime finally crumbled.

Yesterday Mr Cameron addressed TV crews outside Downing Street and was quick to speak by telephone to Mustafa Abdul Jalil, chairman of the Libyan National Transitional Council (NTC). But other leaders were also determined to grab the credit in what became a rather unseemly race. Nicolas Sarkozy, the French President, invited Mr Jalil for talks in Paris tomorrow. France plans to host next week a meeting of the "contact group" of nations trying to stabilise Libya since the anti-Gaddafi uprising began. Silvio Berlusconi, the Italian Prime Minister, whose country was Colonel Gaddafi's strongest EU ally until it switched sides in April, said he will meet Mr Jalil in Italy.

In the long run, this game of diplomatic sharp elbows should not overshadow the significant joint effort by the UK and France; they took the lead in sorting out a problem in Europe's backyard rather than relying on the US. This can only make the growing Anglo-French co-operation on defence happen more quickly. The sense of relief among Cameron allies was palpable. Ministers have been constantly briefed by their officials that Colonel Gaddafi would be toppled eventually. But they were becoming increasingly impatient as the Libyan dictator clung on and the cost of the British operation soared above the "tens of millions" originally estimated by the Chancellor George Osborne. The Treasury now concedes it will be measured in hundreds of millions and some defence experts have predicted a £1bn bill.

There was no crowing or complacency from Mr Cameron yesterday. He acknowledged that "no transition is ever smooth or easy" and that "there will undoubtedly be difficult days ahead", alluding to concerns in Whitehall about the ability of the rebels to deliver a replacement administration when Colonel Gaddafi goes. But there is a genuine hope in Downing Street that the NTC will learn from the disastrous aftermath of the Iraq conflict. Mr Cameron has urged Mr Jalil to respect human rights during the transition process and British officials insist the NTC has got the message.

Mr Cameron has seen off the armchair generals who doubted that Britain would secure a UN Security Council resolution on Libya. Determined to avoid a massacre by pro-Gaddafi forces, he trusted his own instincts and those of his sounding board in the region – the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan. He had a healthy scepticism about Foreign Office experts who failed to predict the Arab spring.

The history books will suggest that Mr Cameron called it right on Colonel Gaddafi whereas the man he often seeks to emulate, Tony Blair, got it wrong by bringing him in from the diplomatic cold. Mr Cameron's success may reinforce his credentials on the world stage and his image at home as a natural leader. But while a stalemate in Libya could have damaged him, he is unlikely to reap any political dividend from the endgame. Voters will judge Mr Cameron more on the performance of the economy and his response to the riots.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments