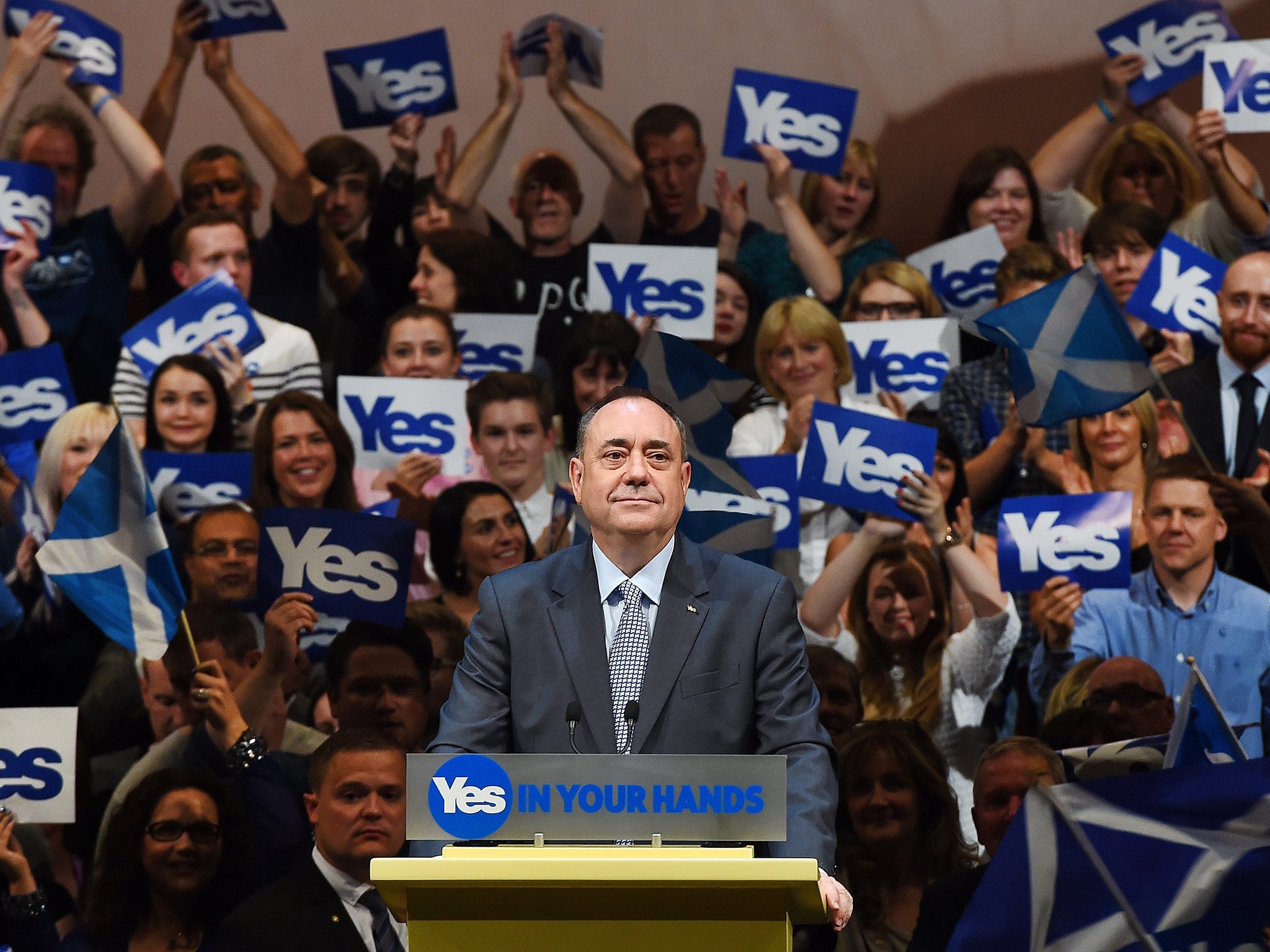

Alex Salmond to stand at general election – but what does he want, can he really get it… and at what price?

Salmond’s announcement today adds more uncertainty to what is already promising to be the most unpredictable general election in living memory

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Alex Salmond first turned up in the House of Commons in 1987, he had an interesting walk on part, as a minor character who cleverly made more impact than his importance warranted, in a party that was far too small to have any impact on national politics.

It will be a very different story if he reappears next year as MP for Gordon – as he almost certainly will. His announcement today should not be equated to Nigel Farage’s decision to contest South Thanet. Farage might not win. If he does, his presence will make Parliament that bit livelier without necessarily having any impact on the government.

Salmond’s return is close to a near certainty, and the only way that it will prove to be a “so what?” is if either the Conservatives or Labour win an outright majority of MPs, and can therefore govern without help or support from other parties.

But all the opinion polls are telling that a majority for either of the big parties is highly unlikely, unless the public mood changes drastically in the new year. What the polls are currently suggesting is that on Friday, 8 May, we will back to the same constitutional confusion that reigned for five days after the 2010 general election – only this time, it could be a lot more confusing.

The usual procedure in a hung parliament is that the biggest party does a deal with the third biggest – and for as long as any can remember, the third party has been the Liberal Democrats or their predecessors, the Liberals. They have always had enough MPs to give the biggest party a clear majority, creating an arrangement that has worked for David Cameron and worked - after fashion - for James Callaghan in the 1970s.

But who says that the Liberal Democrats will be the third party after next May? Their poll ratings are so dismal, and the SNP are on such a roll, that Alex Salmond could be leading such a contingent of MPs big enough to prevent either party entering into a stable coalition with the Lib Dems without SNP support.

That is bad news for David Cameron, because Alex Salmond said categorically today: “We will not deal with the Conservative Party in any form.”

But it is not brilliant news for Ed Miliband either. Though it adds to his chances of being the next Prime Minister, the price would be high. Salmond is a very experienced, hard-nosed operator who will not sell his support cheaply, but the Labour leader is not going to want to be the Prime Minister who presides over the dismantling of the United Kingdom, any more than David Cameron did.

Salmond’s announcement today adds more uncertainty to what is already promising to be the most unpredictable general election in living memory.

Salmond has indicated where bargaining begins. He does not think that the recommendations of the Smith Commission that reported on increased powers for the Scottish Parliament went anything like far enough. In particular, he complained today that 70 per cent of the taxes Scots will pay will still go to the treasury, in London, rather than to the Scottish government. We can assume he would begin by demanding greater tax raising powers for Holyrood.

His next demand, if he thinks he can get away with it, might be to remove Trident from Scottish soil.

But any other reform he extracts is but a step towards the ultimate goal. Salmond has not accepted that the comparatively narrow defeat that the independence campaign suffered in September’s referendum is the last word.

If his hand is strong enough, he will say to Ed Miliband: “You can be Prime Minister for five years, but the deal is another Scottish referendum on your watch.”

It is a concession that the Labour leader will desperately want to avoid.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments