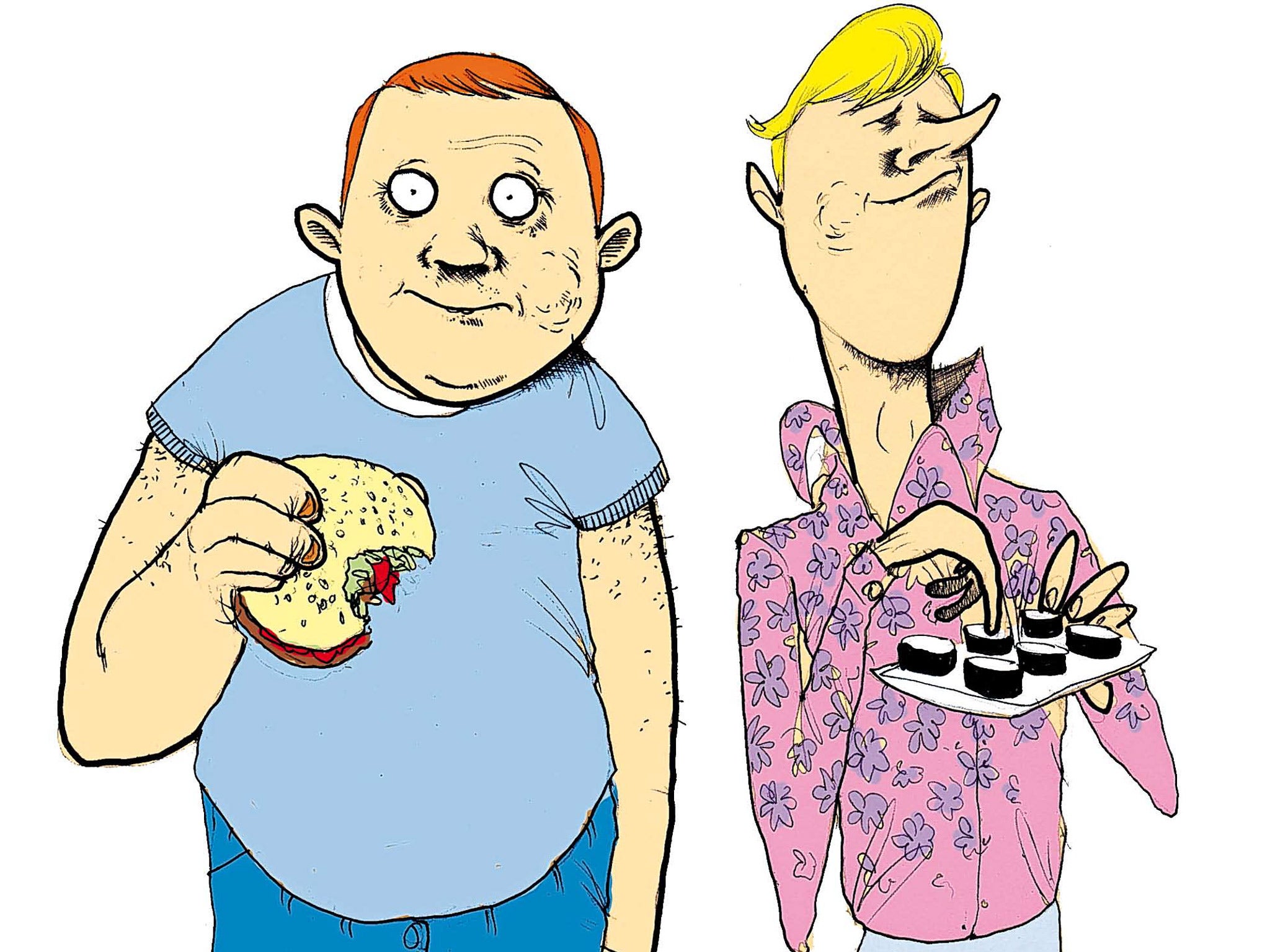

A fat lot of good that will do: minister loses health argument by stereotyping the poor

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Anna Soubry may have thought she was making an innocent observation about the nature of society when she declared that she could recognise the poor because they were fat.

“When I walk around my constituency you can almost tell somebody’s background by their weight. Obviously not everybody who is overweight comes from a deprived background but that is where the propensity lies,” she said

The public health minister’s remark in a speech to the Food and Drink Federation, the industry organisation whose members produce the building blocks of the obesity epidemic, triggered instant outrage, beginning with a torrent of protest.

“Defiantly tucking into my breakfast bun,” said one tweeter, “She’s a car crash of a minister,” added another. “Thinking of organising a whip round for [portly cabinet minister] Eric Pickles,” joked a third. Her Labour shadow, Diane Abbott commented: “Talk about blaming the victim.”

The 56-year-old Conservative MP for Broxtowe, Nottinghamshire, was speaking at a conference where she warned food manufacturers they must move faster to cut the amount of fat, sugar and salt in their products or face legislation to make them do so. It was “an abundance of bad food” that was responsible for the soaring rates of obesity, and it was up to the industry to do something about it.

Burger bars and fried chicken shops proliferate in poorer areas, their greasy smells enticing a ready clientele. But efforts to restrict their number, or improve their fare, have largely failed. Food firms have instead been invited to voluntarily introduce healthier formulations under the much derided “Responsibility Deal”. Progress has been slow. Today’s announcement of an 8-10 per cent cut in the sugar levels in Ribena and Lucozade soft drinks was scorned by campaigners as “unimpressive.”

Ms Soubry’s efforts to focus attention on the food industry were in vain as it was her remarks about the eating habits of the poor that seized the headlines.

Recalling her childhood in the 1960s, she said when she was at school, the deprived children were easily identifiable because they were “skinny runts”. Not any more. A third of children leaving primary school today were overweight or obese.

She placed the responsibility squarely on their parents, not the manufacturers of the products that made them fat whom she was addressing. Parents should ensure they had family meals instead of letting children “graze” or eat while watching television.

“What they don’t do is actually sit down and a share a meal round the table. There are houses where they don’t have dining tables. They will sit in front of the telly and eat,” she said.

The Department of Health confirmed that the poorest children are twice as likely to be obese as the rich. But the true picture is more complex. The Health Survey for England, published last month, shows that, among boys aged 2 to 15, obesity does indeed decline as families move up the income scale, from 25 per cent in the most deprived to 7 per cent in the second richest. But in the richest families at the top of the income scale, obesity rises again to 14 per cent.

Better-off children may have more pocket money to spend on snacks and more freedom to spend it, especially if they have two working parents, absent from home at the end of the school day.

Among girls, obesity is lowest in the richest families at 5 per cent. But although it rises as income declines, it peaks at 22 per cent in the middle income band before falling back amongst the second poorest families to 12 per cent and then rising again in the poorest to 19 per cent.

Among adults, obesity was lowest for both men and women in the richest two income bands, ranging from 20 to 22 per cent, and highest in the three poorest income levels, at 25-32 per cent.

Tam Fry, spokesman for the National Obesity Forum, attacked Ms Soubry for “stigmatising” the poor. “It was the tone of what she said. It was arrogant and condescending. Yes it is true that the lower down the social scale you go the more likely people are to be obese.”

“But the poor are unable to buy good food. It may not cost more but it takes more time to get and to prepare. People who are less wealthy eat the food that is least healthy. It is the way the food is processed by an industry that puts in fat, and salt and sugar that degrades it.”

Ministers and officials have in the past avoided targeting particular social groups on obesity. The last national campaign to tackle the problem, launched in October 2011, was presented as a drive to “cut five billion calories a day” from the nation’s diet.

Fat children tend to grow into fat adults, and experts agree on the importance of nipping the problem in the bud. But parents often do not recognise their children are fat. Since 2008, parents have been told if their child is overweight when they are weighed and measured at school – whereas previously they had to ask for the results. But even now the word “obese” is banned for fear of stigmatising the child.

The driver of the obesity pandemic has been known for 40 years, scientists declared at a UN conference in 2011 – a food industry bent on maximising profits. But governments have turned a blind eye, fearing nanny state accusations, and insisted instead that it is a matter of individual responsibility. Now Anna Soubry has joined them.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments