My war on terror and Abu Hamza: Reda Hassaine on battling Islamic extremism

For two decades, Reda Hassaine has been working alongside security services. Here, in an exclusive extract from his new book, he reveals his frustration about being ignored in the aftermath of 9/11 and his grim satisfaction at the forthcoming sentencing of Abu Hamza, who he helped to convict

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Terrorism thrives on manufacturing chaos and spreading fear. In the heat of battle, it is sometimes difficult to make sense of who is fighting whom, and why. For 20 years, I have felt like I was in a battle for survival in which I – an ordinary Muslim democrat – tried to face down jihadist theocrats who have a profound hatred of democracy.

My engagement with the men of terror started in the first years of the Algerian civil war (1991-2002) when I became an informant. At first, I was the eyes and ears of the opposition to state terror in my homeland and then to global jihadism, which first found its expression in Algeria. For nearly two decades, it was my job and my duty to take sides and I paid a heavy price. My story is the tale of one Muslim's battle to overcome the evils of Islamist terror.

Looking back to 1994, I recognise I was naïve enough then to believe that I could somehow get the three security services of Algeria, France and the United Kingdom to work together to combat those who used human rights laws to evade prosecution and conviction. I assumed that if the security services had the right information they would act accordingly. They did not. American security services seemed deaf to my pleadings, too. But I didn't give up. As it became clear that the fanatics were increasingly focused on causing harm to the United States, I realised I would need to try to use my journalism networks to make their citizens see the dangers, too.

At the start, all a jihadi terrorist had to do was to cross an international border and find a more laissez-faire regime to continue their work. Naïvely, I thought that by using my intelligence-gathering instinct and doing the agencies' joined-up thinking for them, I might actually help thwart terror attacks in my new homeland of Britain? . My instincts told me that the terror would spread – as it subsequently did to the Paris Metro in 1995 – but no one could have imagined the scale and impact of 9/11, and then the 7/7 bombings on the London Underground.

To this day, I regret that my constant ravings to the British security services, including Scotland Yard, were only heeded after the mass slaughter on the Tube. I was profoundly depressed in its aftermath (in fact, doctors said I was close to a breakdown). I still believe that the Tube bombings of 7 July were preventable. "For what reason do you suppose these young British men are being sent to Afghanistan?" I asked of my handlers on many occasions.

Why didn't they listen to me?

Of course, they had their own value system which made it hard for them to believe a foreigner like me, even one from terror-bedevilled Algeria. They repeatedly told themselves that suicide bombings in London were impossible. They didn't understand that British boys in the hands of terrorists would adopt a value system of hatred, annihilation and martyrdom. I did understand. I had been in Algeria and seen the corrupting force of terror first-hand. In retrospect, perhaps they didn't value the information I gave them. There were clues in the fact that they paid me a pittance, which I should have recognised as a sign of them not valuing my information. I believe Britain paid a heavy price for distrusting a double agent.

My mantra was simple. Anything is possible – it can happen. Moreover it will happen if you don't do something about these fanatics. It was a mantra that sent me to the edge of madness. I told the security services and eventually anyone else who would listen, "They are being trained to come back and murder as many of you as possible." My greatest fear in all that I did and said was that I wouldn't be believed and I would be taken for a madman. I very nearly succeeded in fulfilling my worst fears.

Eventually, in Britain I found journalists courageous enough to publish what I said. But then it was almost too late to prevent full-blown terror attacks. The genie had been let out of the jihadist bottle. As a witness to history, I want others to know that the evidence of terror was not hidden.

Many of us could see how the spirals of terror fomented by the state in Algeria and the reciprocal terror of those that opposed them in the Groupe Islamiste d'Algerie (GIA) inevitably became so ferocious that the fates of hundreds of thousands of ordinary people got mangled in the process. In these circumstances, you either joined in, you opposed, or you got mangled. No one makes his way through these killing fields unscathed.

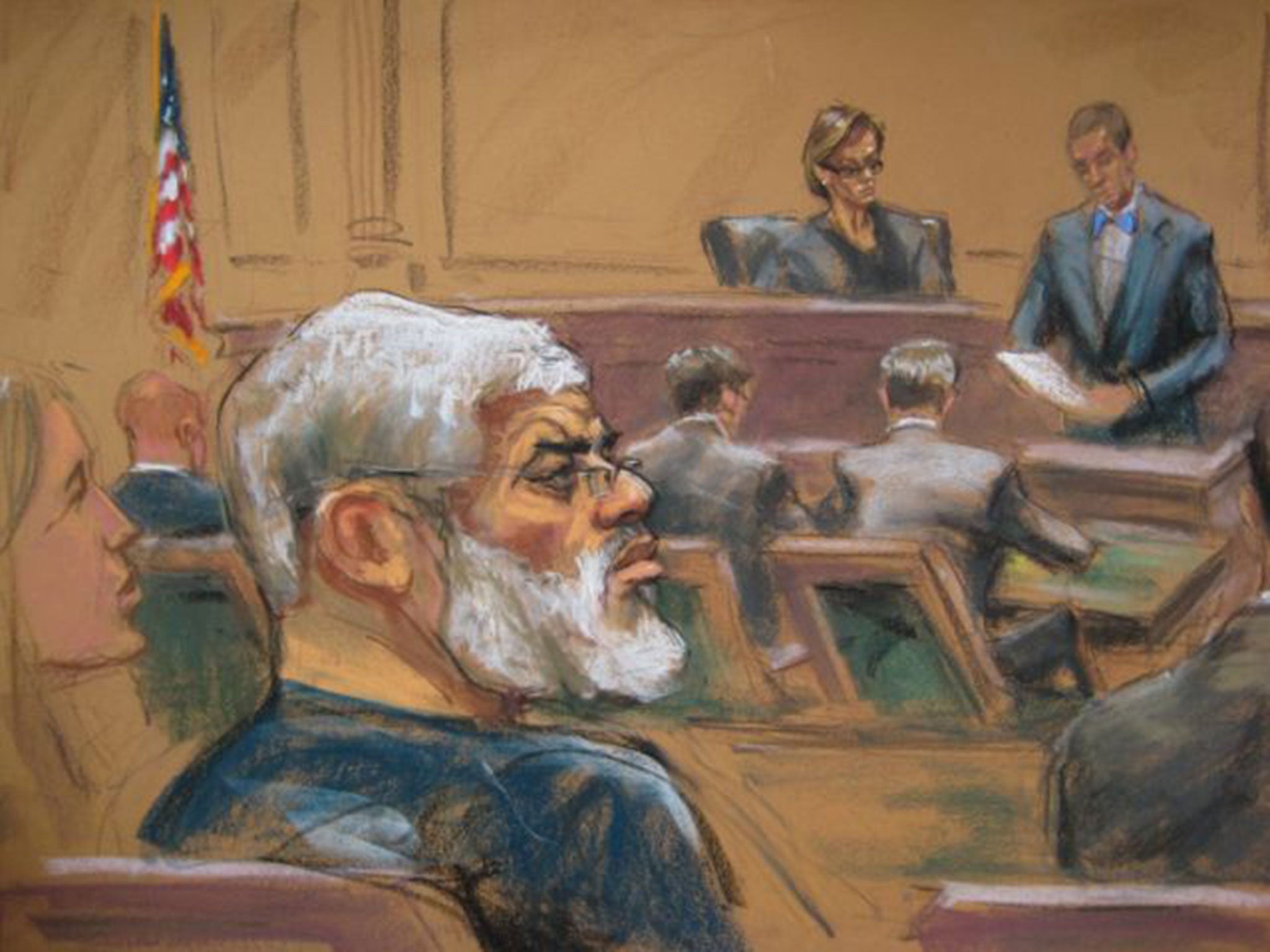

Mine has been a dangerous and complicated life. But the truth is, my determination to fight against the terror that blighted my country was unshakeable. Combating criminals who use religion to satisfy their thirst for blood was a duty for me, I suppose a kind of civic jihad. I, too, believed that if I died as a martyr for the cause of democracy I would be able to take 40 people to paradise and I would reserve places there for my family and friends. I feel exhausted, yes. But after 20 years' fighting terrorism – much of it trying to expose the firebrand Muslim cleric Abu Hamza – the guilty verdict handed down to him in America this year was a personal victory for me. For supporting terrorism – for which he was arrested in 2004 and extradited in 2012 – Hamza will be sentenced to at least one life's imprisonment this month. I feel I have accomplished my mission as best I could and for the right reasons.

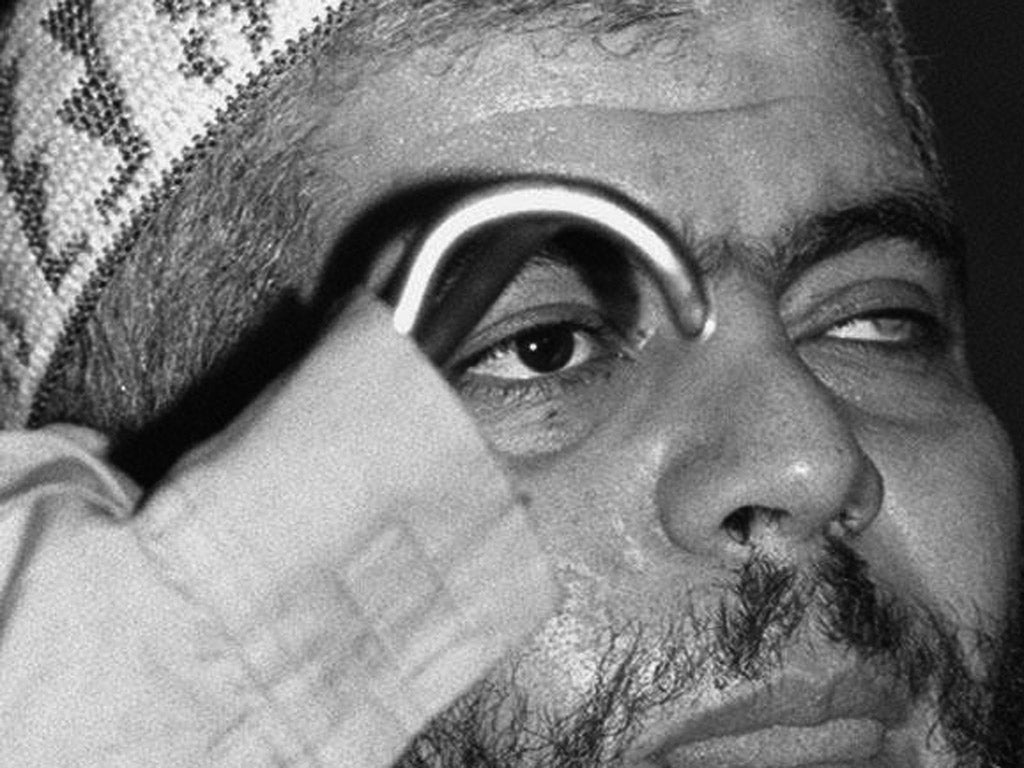

Hamza made his Islamist name in the Bosnian and Afghan wars. Now, as he faces the reckoning for his crimes, all his pretences of importance and status within his revolutionary world have been stripped away. Referred to in court by his real name, Mostafa Kamel Mostafa, he is reduced to facing the consequences for his millions of words of hate and incitement, which all the world knows incontrovertibly led to the violent actions perpetrated by his followers.

And that includes all the British-born young men and women who have recently travelled to Syria from Britain to join in the fight with jihadist forces. They may have been encouraged by a new generation of radicals, preaching their ideas of a radical Islamist Caliphate, but Abu Hamza helped prise open the lid of the Pandora's box. For that reason he will always to me be the godfather of British jihadism.

In the early Nineties, Finsbury Park Mosque was a haven for many Algerian anti-government exiles; and Hamza, who in 1996 became its imam, was an incredibly charismatic figure. He appealed to young men who felt marginalised in their own communities. He would sit for hours cross-legged on the floor talking to youths from Britain's Asian Muslim communities – second-generation Bangladeshis and Pakistanis – as well as Somalis and some Afro-Caribbean boys who'd converted to Islam while in prison. They would watch videos together of battles in war-torn territories and Hamza would implore the youngsters, some only in their mid-teens, to see that their Muslim brothers needed support against the forces of the West ranged against them. These videos were brutal, showing decapitations and body parts, completely uncensored and used purely to shock and radicalise the viewer.

Finsbury Park Mosque was an ideal place for young men without jobs or purpose to come for camaraderie. Most didn't smoke, drink or do drugs – such was their religious commitment. They didn't have girlfriends or go to all-night parties. The levels of testosterone were palpably high and the basement gym was well used. Kick-boxing and other martial arts competitions were a regular feature of mosque life.

Given money when they needed it, these youngsters were slowly pulled into the orbit of the other battle-hardened veterans who then determined when a recruit was ready for a trip overseas to a training camp. Not only was the mosque secure (in the sense that no white man could step inside the place unless he was a known convert) it helped provide contacts in Pakistan and onwards to Afghanistan. I saw it increasingly as an al-Qaeda guesthouse in London. When combatants returned from foreign wars they would exchange stories with wide-eyed kick-boxers, making them ready for Abu Hamza to step in and finish the job of brainwashing them.

Many people beyond the Mosque saw Hamza as a buffoon – he was always ranting, he often misquoted scriptures, he said things that were simply so outrageous they seemed laughable – but within the mosque it was no laughing matter to see young men come under his influence. They were dicing with their lives.

Drawn by Hamza's radical reputation, more and more worshippers came to use the place as a hostel. In his view, he had become a true leader. His congregation admired him and his ego was growing with every news headline. With no one to keep him in check, he probably felt untouchable.

To his followers, his boasting was a rallying cry for the jihad that they believed was now unstoppable. By the turn of the millennium, Finsbury Park Mosque had been elevated in jihadi circles to a place where recruiters could attract passionate young men – often disillusioned with life in Britain – and dispatch them for weapons and terror training in Taliban-run Afghanistan. Once, Hamza had preached resistance in Algeria. Now the prize was a spreading conflict that they hoped would end at the doors of the Great Satan – the United States of America.

The mosque's notoriety grew. With the influx of many more worshippers (including spies from other intelligence agencies – I was never under the illusion I was alone) the collections of money continued apace. And at the heart of it all was Abu Hamza. He was emboldened – but to my ever-growing frustration, the British authorities were apparently taking little notice of my warnings. He now called himself Sheikh Abu Hamza, – a religious honour? – but from where I was sitting he looked like the terrorist-in-chief, ever more respected by his followers and operating in contempt of the police authorities I was informing.

Is it unfair to say that the security services were paying no attention in the early years of the last decade? They were certainly taking a keener interest in the comings and goings at Finsbury Park, but they seemed incapable of putting the mosque in its proper al-Qaeda context. They continued to view it as a little sideshow run by a clown.

Well, he may have been a clown. But his antics captured young Islamists' attention, kept it and inspired them to reach for martyrdom. In Algeria, Britain and internationally, he didn't do it alone, but he was a big fish among minnows. A generation that does not share his views will now try to come to terms with what this means for them.

Radicalisation of young minds eager for a different way to interpret the world is far from over. Our work is not yet done. But at least, albeit belatedly, Abu Hamza has finally been held accountable for the thousands of deaths inspired by his calls for violent jihad. This sends an important message that, no matter how long it takes, if you act criminally you will eventually face justice in the West. For those of us who believe in a world where dissent matters, where minorities are accorded the same protection as the majority, and where you do not risk death because you believe in a different god, justice has been done.

Abu Hamza, or should I say Mostafa Kamal Mostafa, for all these reasons I am certain that there will be no place reserved for you in paradise.

'Abu Hamza: Guilty – The Fight Against Radical Islam', co-authored by Réda Hassaïne and Professor Kurt Barling (Redshank Books, £9.99) is now available on Amazon and in bookstores

Trip to ground zero

From Charleston, I had one more thing to do before ending my short but productive trip to America in February 2005. I had managed to pull together my meagre savings so I could travel to New York. I couldn't return to England without seeing this place.

The following morning at breakfast, I could feel my heart racing with the anticipation. Perhaps it was my blood boiling more than my heart racing. Finally arriving in New York was my chance to give my apologies and prayers to the victims for not having succeeded early enough in my mission.

At Ground Zero, the tears came as I asked myself did I dream too much and do too little? As I wandered off to take a boat to Ellis Island and continue my short trip of discovery around New York, I consoled myself with the defence that I had refused to believe that nothing could be done. I had done my very best to warn others by going public and warning the Western world of the real dangers they were facing from these merchants of terror passing through Finsbury Park Mosque under the stewardship of Abu Hamza.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments