Wrongly convicted men launch new case against the Justice Secretary

Chris Grayling's changes to existing law will leave victims of miscarriages of justice with no compensation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Victims of two of Britain’s most worrying miscarriages of justice of modern times are to take the Justice Secretary, Chris Grayling, to court over changes to the law stopping them from receiving compensation for the 24 years they wrongly spent behind bars.

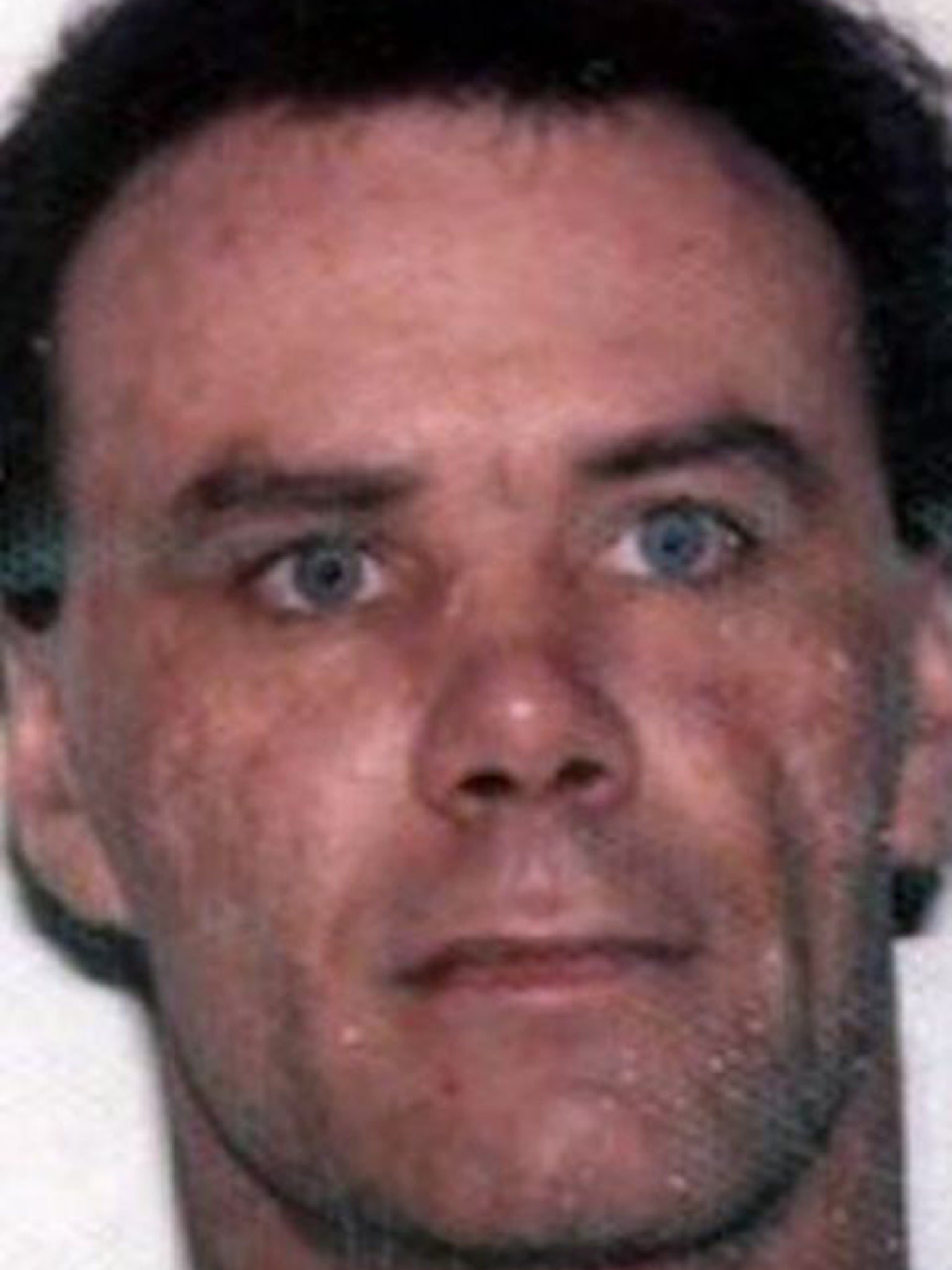

Victor Nealon, who spent 17 years in prison for attempted rape before his conviction was quashed, has begun legal action after being left penniless, suffering from post-traumatic stress and unable to work as a result of his wrongful imprisonment. He has been joined by one of Britain’s youngest miscarriage of justice victims, Sam Hallam, who, aged 17, was convicted of murder after a trainee chef was stabbed during a fight in London.

Mr Hallam’s conviction was thrown out by the Court of Appeal in 2012 after he spent seven years in jail. Judges heard that crucial evidence supporting his alibi had been left undiscovered on his mobile phone for years.

The legal challenge is seen as a test case for a new stricter regime to compensate the victims of miscarriages introduced last year. Crucially, it changed eligibility for compensation which means it paid only when the new facts resulting in the quashing of a conviction shows “beyond reasonable doubt” they did not commit the offence.

Barrister Baroness Helena Kennedy called the change “an affront to our system of law” when the Bill was debated. “When people have wasted long periods of their life in jail for crimes they didn’t commit, the least society can do is provide some compensation,” said Sadiq Khan, the shadow Justice Secretary. “This government was warned the changes would place too great a burden on the victim to prove their innocence, even after they’d been freed from jail. It’s a mark of a civilised country that when mistakes of such a serious nature like this are made, the Government should pay compensation to make up for the error. The rules require review urgently.”

Mr Nealon, a former postman, could have been released after seven years but was rejected for parole because he refused accept guilt or undergo rehabilitation to address his “crime”. Mr Nealon, who already had a criminal record, was arrested because he resembled the victim’s description of a man with a pock-marked face. The evidence used to secure his conviction was a disputed ID parade and a weakened alibi. Both Mr Hallam and Mr Nealon consistently protested their innocence.

“Victor Nealon continues to suffer at the hands of the state,” said his solicitor Mark Newby. “He now has to fight for the compensation he should be entitled to. It is wrong to deny a man his liberty for the best part of two decades and then to do everything possible to avoid compensating him. We are determined to see these legal challenges through to the end, whether that is in the UK or Europe.”

The new legislation follows the previous Labour government’s curtailment of compensation paid out to the victims of miscarriages of justice. In 2007, the former Home Secretary Charles Clarke decided, without consultation, to scrap an ex gratia scheme. The move was attacked as “monstrous” by the Cambridge University law professor John Spencer QC .

The human rights group Justice said the 2014 legislation was deeply concerning. “In our view, the change in law offends the right to the presumption of innocence and makes an award of compensation almost impossible to achieve,” said Jodie Blackstock, director of criminal policy at Justice.

“With no support available to released people, they continue to be wrongfully persecuted by the state.”

Mr Nealon’s conviction was quashed after DNA evidence pointed to the fact another man was behind the attempted rape in 1997 outside a nightclub in Redditch. Following Mr Nealon’s acquittal, West Mercia police is reviewing the case. A police spokesman warned the review might “take a considerable amount of time” given the period since the offence was committed.

In his written decision not to pay Mr Nealon, Mr Grayling accepted it was a “real possibility” that an unknown male was behind the attack and not the 54-year-old. But in the grounds for resisting the claim it was asserted that the DNA analysis “plainly did not show beyond reasonable doubt the claimant did not commit the offence”.

However, the minister went on to assert there was “nothing in that conclusion that affects the claimant’s entitlement to be presumed innocent of the offence itself. Nor is there anything in the language of the Secretary of State’s decision applying those criteria [of the new legislation] which infringes that presumption”.

A Justice Ministry spokesperson said: “There is no automatic entitlement to compensation but every application is considered on its merits. It would be inappropriate to comment on the details of any individual’s case.”

‘My resolve was to clear my name. I don’t want to let this affect me for the rest of my life’

On the night of the attempted rape that put him in jail for 17 years, Victor Nealon was at home watching prison-themed movies with his partner. They saw Lock Up – a Sylvester Stallone film – and The Shawshank Redemption, the Oscar-nominated prison drama starring Tim Robbins as a man who struggles in prison after being wrongly convicted of murder.

Nearly 19 years later and the euphoria of his own release long past, Victor Nealon’s life is grim. His parents died while he was in jail and he lives alone. Prospective employers treat him with suspicion. He lives on benefits. He sees his doctor once or twice weekly and gets medication to help him through the nightmares.

His medical problems stem from his treatment in prison. “It’s one thing to lose your friends, family, freedom, money and job. It’s quite another to be told that if you don’t confess to the crime you’ll never be released,” he said. He maintained his innocence even though it cost him an extra seven years in prison. He had three hours’ notice of his release, was given a train ticket and £46. He spent it on a room in a B&B.

“If you don’t co-operate with the prison system, you are a nonentity. It tries to force and compel you to do rehabilitation work. If I was to do it I would have to admit my guilt, and I wouldn’t do that. My resolve was to clear my name. I don’t want to let this affect me for the rest of my life. I’m living below the poverty line, but I have a degree of optimism because I have a case worth fighting and I’m not going to give up. I’ll fight as long as it needs to be fought.”

Jon Robins and Paul Peachey

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments