UK Jewish Orthodox councils 'institutionalising marital captivity and upholding discriminatory religious laws'

Orthodox councils should be subject to scrutiny alongside sharia courts, says academic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jewish Orthodox councils in the UK are “institutionalising marital captivity and upholding discriminatory religious laws” that victimise women and secular alternatives need to be introduced by politicians, according to an academic study being launched in Parliament.

New laws should be enacted in Westminster to give women of all faiths equal access to end their marriages, said the researcher Machteld Zee, ahead of releasing a book regarded as perhaps the most comprehensive analysis of religious courts in the UK.

The study by Ms Zee, from Leiden University in the Netherlands, first came to attention last month when The Independent revealed her findings that Muslim sharia courts allegedly set out to frustrate women whose husbands do not want them to leave. Her work has been backed by the crossbench peer Baroness Cox, who is sponsoring a law that could restrict religious courts and calls Ms Zee’s evidence the “tip of the iceberg”.

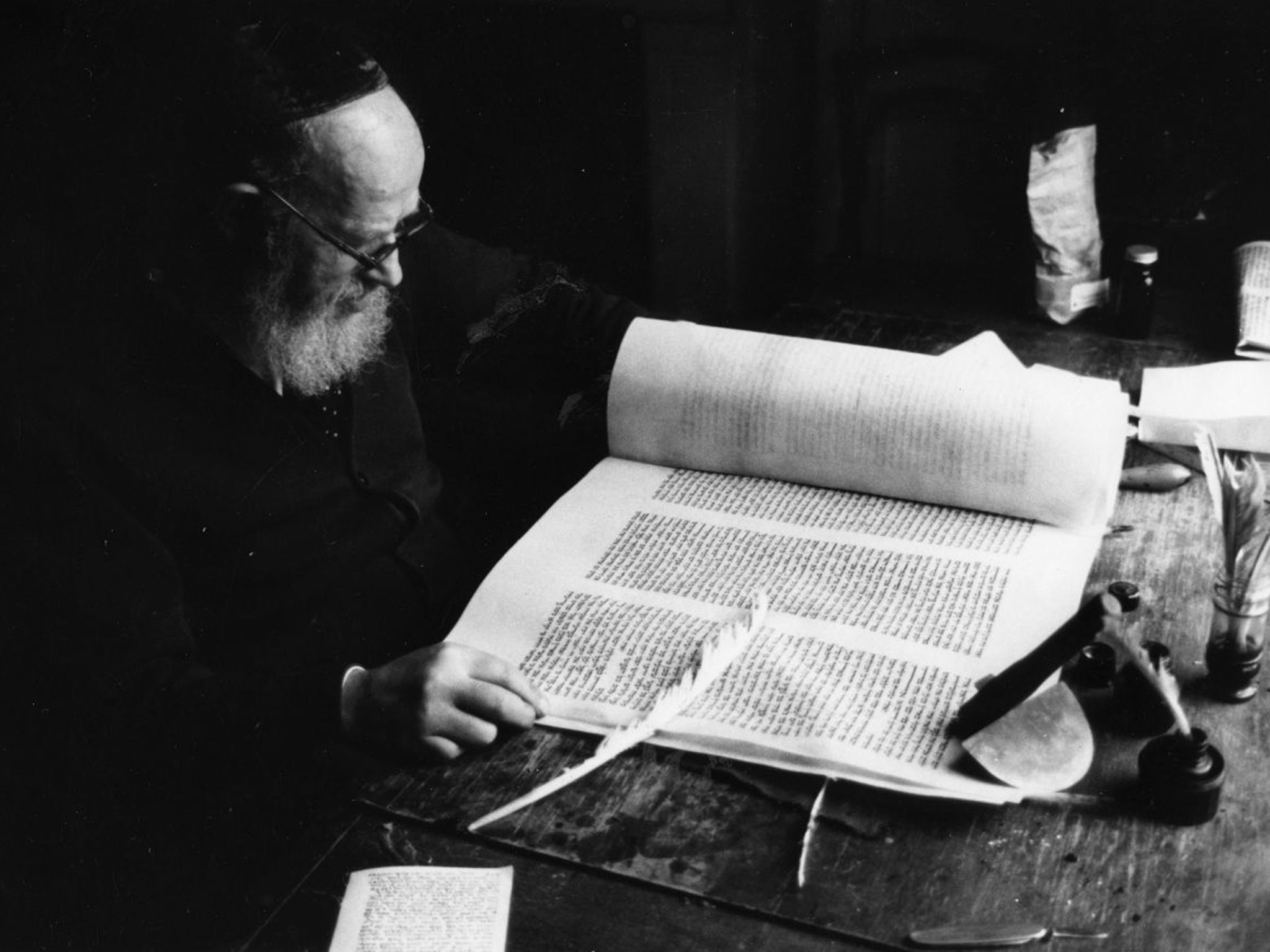

The academic, whose book will be launched on Tuesday at a House of Lords event chaired by the former High Court judge Baroness Butler-Sloss, said there were striking similarities between sharia courts and Jewish Orthodox Beth Din councils in how they deal with women seeking a “religious divorce”.

According to Jewish law, both spouses must consent to a religious divorce. But it is executed by a writ – the “get” – delivered by the husband, of his own free will, which the wife needs to accept.

Without a get, any future offspring of the woman – and nine generations of children – will be “mamzerim”, and would only able to marry another “mamzer”.

Ms Zee said the Jewish councils deserve scrutiny as well as sharia courts, because they contribute to women remaining in “marital captivity”. The academic said that while the rights of faith groups to follow their beliefs were important, some practices are in breach of a UN treaty – the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women – and need to be reformed.

“Jewish law is religious law based on domination over women,” Ms Zee told The Independent. “The point is, with both sharia courts and Jewish courts, women may not decide freely whether they exit a marriage.” She said the UN treaty “is very clear on that”.

Sharia councils and Batei Din operate as bodies under the Arbitration Act 1996, to resolve disputes among community members.

But Ms Zee – the author of Choosing Sharia? Multiculturalism, Islamic Fundamentalism and Sharia Councils – challenges their status as arbitrators. She claims they are not independent and often act for one party rather than as a mediator.

“Like Muslim women, Jewish women often find themselves at a disadvantage in the religious divorce process,” Ms Zee argues in her book.

“Unlike sharia councils, where a qadi can issue a divorce in the absence of a husband, it is not possible for a Jewish woman to obtain a get without her husband’s co-operation (at least, not according to classic interpretations). In that vein, a Beth Din does not function as a ‘court’; it is a witness to the dissolution of the marriage.”

She alleges that, in theory, Jewish women can be worse off than Muslim would-be divorcees. A sharia council can issue a divorce without the man’s involvement.

In contrast, the Divorce (Religious Marriages) Act of 2002 specifically applies to the “usages of the Jews” and means a civil judge can withhold divorce until a religious divorce has been carried out.

But, she adds, other religious groups such as Muslims would have to “opt in” to this legislation, and have not done so. In practice, she says, most Jewish women have civil divorces and are aware of their rights, so this act “is successful within the Jewish community”.

The Arbitration and Mediation Services (Equality) bill, sponsored by Baroness Cox, is expected to complete its final stage in the House of Lords this month, then move to the Commons.

This law would make it a crime for an arbitration service “falsely claiming legal jurisdiction”. A spokesman for Baroness Cox said that if there was “a problem in Jewish communities of women being pressured to participate in ‘voluntary’ or ‘consensual’ arbitration”, the Bill will affect a Beth Din “in the same way as it will affect the sharia courts.”

Baroness Cox said Batei Din do not purport to be legal courts, but if women were pressured to go there, her legislation would apply.

The law is going through Parliament at a time of fierce debate over religious councils. The book predominantly focuses on criticisms of UK sharia councils, to which Ms Zee gained access to observe hearings in 2013. The Jewish aspect of the book was informed by studies of academic literature, interviews with an Israeli scholar and two leading rabbis from the London Federation of Synagogues, a Beth Din in London.

Her criticisms of sharia courts have upset some. Khola Hasan, a scholar at the Islamic Sharia Council, said Zee’s PhD thesis – the basis of the book – was: “Factually inaccurate, distorts case studies, makes wild accusations about individuals, misinterprets history, manipulates world events to conform to her agenda and is generally a huge farce.”

The book’s assessment of Batei Din is likely to prove controversial to some Jewish groups too.

In recent months, the London Beth Din has twice resorted to “naming and shaming” men who were refusing their wives a get, by sending posters to synagogues publicising their details and photographs. They have called on the men to “do the right thing”. But David Frei, registrar to the London Beth Din, said he did not accept the criticisms in Ms Zee’s study. “There is a worrying trend that sees anything associated with religion as prejudiced, flying in the face of modern life,” he said.

“The key British values of tolerance and mutual respect are essential tenets of Jewish law. As Jews, we are proud citizens, fully integrated within British society and it is a privilege that our rabbinical courts have for over 200 years worked hand in hand with the British legal system.

“Our judges discharge their duties in an independent manner, at all times conscious of the strictures of British law. ”

But Ms Zee believes there is a fundamental point of principle when it comes to human rights. “It’s crazy to say that for Muslims or Jews or another religious group with unequal marriage rights, that there should be separate laws,” she said – adding: “It’s not racist to think that every citizen should have the same laws.”