The Rothschild Libel: Why has it taken 200 years for an anti-Semitic slur that emerged from the Battle of Waterloo to be dismissed?

Thirty years after the dust had settled on the fields of Waterloo, a poisonous anti-Semitic pamphlet circulated in Europe, claiming the Rothschild family had accrued its vast wealth on the back of Wellington's triumph. The 'facts' were entirely made up

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

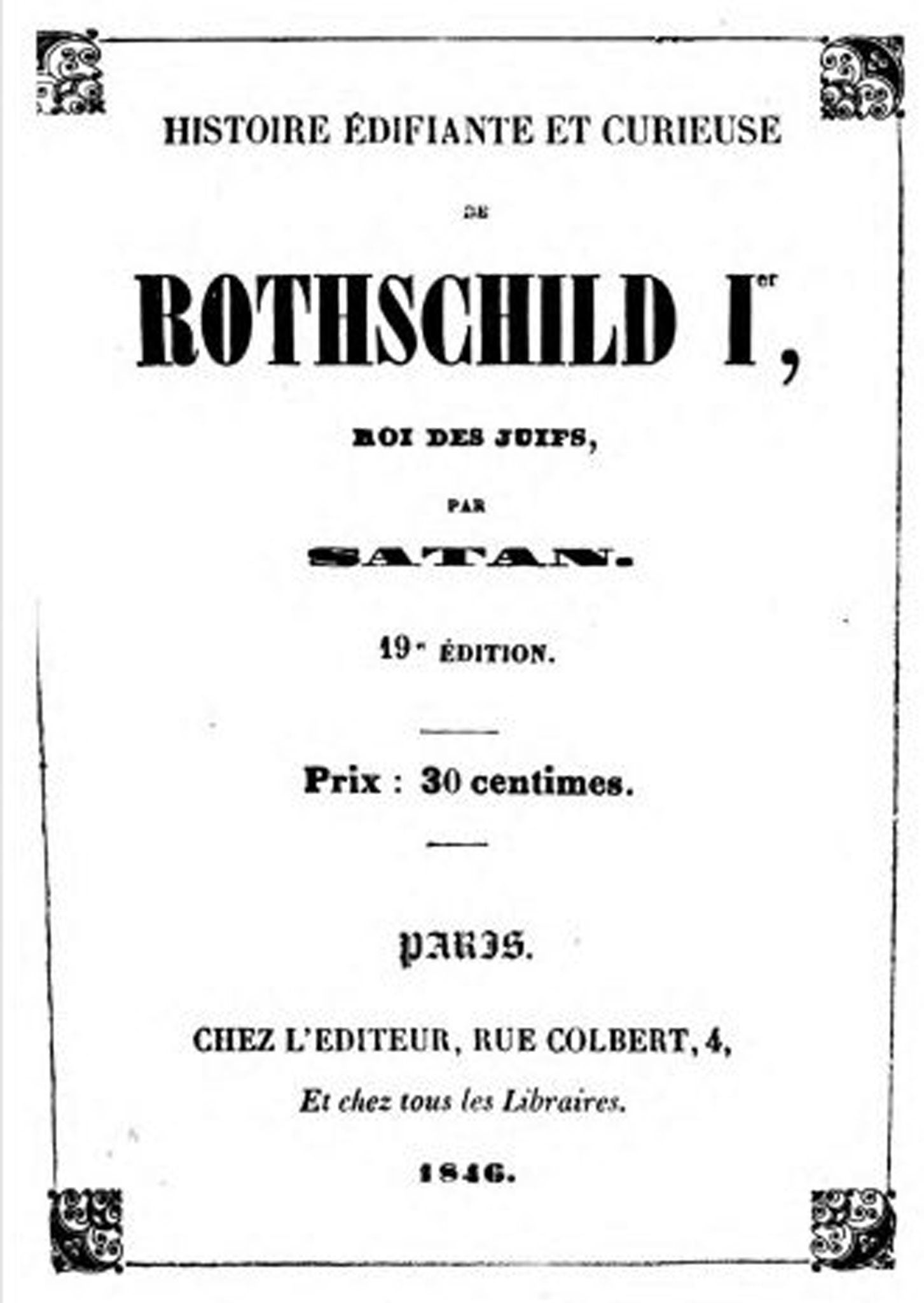

Your support makes all the difference.In the summer of 1846, a political pamphlet bearing the ominous signature "Satan" swept across Europe, telling a story which, though lurid and improbable, left a mark that can be seen to this day.

The pamphlet claimed to recount the history of the richest and most famous banking family of the time – the Rothschilds – and its most enduring passage told how their vast fortune was built upon the bloodshed of the battle of Waterloo, whose bicentenary falls this year.

Here is the story that "Satan" told.

Nathan Rothschild, the founder of the London branch of the bank, was a spectator on the battlefield that day in June 1815 and, as night fell, he observed the total defeat of the French army. This was what he was waiting for. A relay of fast horses rushed him to the Belgian coast, but there he found to his fury that a storm had confined all ships to port. Undaunted – "Does greed admit anything is impossible?" asked Satan – he paid a king's ransom to a fisherman to ferry him through wind and waves to England.

Reaching London 24 hours before official word of Wellington's victory, Rothschild exploited his knowledge to make a killing on the Stock Exchange. "In a single coup," announced the pamphlet, "he gained 20 million francs."

Beyond all doubt this tale was anti-Semitic in intent. Satan was in reality a left-wing controversialist called Georges Dairnvaell, who made no attempt to hide his loathing for Jews –and the Rothschilds in particular. Though they had been little known in 1815, by 1846 the Rothschilds had become the Rockefellers or the Gateses of their age, their name a byword for fabulous wealth. Nathan himself had died in 1836 and so could not rebut the claims.

Every aspect of Dairnvaell's tale – the ruthlessness, the guile, the greed – represents a derogatory racial stereotype, and he was writing at a moment when such attitudes were having one of their periodic surges of popularity in Europe.

The story was also false: Nathan Rothschild was not at Waterloo or even in Belgium at the time. There was no Channel storm. And he made no great killing on the stock market.

Yet the Satan pamphlet, translated into many languages and reprinted many times, gave this legend such a grip on history that, albeit often in modified or diluted forms, references to it can still be found today both in popular culture and in scholarly works.

Versions appear in a Hollywood film of 1934 and the 2009 Sebastian Faulks novel A Week in December; in past editions of the Dictionary of National Biography and Encyclopaedia Britannica; in Elizabeth Longford's acclaimed 1970s biography of the Duke of Wellington; and (with a very different analysis) in Niall Ferguson's authorised history of the Rothschilds. Perhaps more predictably, the story provided the plot for a Nazi film of 1940 entitled The Rothschilds: Shares in Waterloo, and the tale can be read on many anti-Semitic websites.

How does a crude racist smear endure for so long? More importantly, how has it survived as a supposed sub-plot of history – towards which even the most respected writers have felt obliged to nod – when it is one of those myths that, on being challenged with inconvenient facts, simply adjusts its form? For example, when it was finally accepted that Nathan Rothschild was definitely not at Waterloo, the story changed: the banker was in London, but had made elaborate preparations to get the news first, either by special messenger or pigeon post. An additional twist was added. Once he knew Wellington had won, Rothschild was said to have deliberately provoked a collapse of the stock market by spreading false rumours of a defeat, so allowing him to pick up shares at rock-bottom prices and double his profits later, after official news of the victory had sent the markets soaring.

Was there any truth to this revised version, or to any of the other variants that have surfaced over the years? We will come to that.

The legend has had innocent uses – for example, the former CIA chief Allen Dulles repeated it in a 1963 book on espionage as he wanted to illustrate the value of early information. Other writers have adopted the tale simply as a good yarn, without any anti-Semitic intent.

Even the Rothschild family, always deeply uncomfortable with the story, has tried to domesticate it. Their preferred version glosses over any alleged profits and stresses that Nathan's first action on hearing of the victory had been that of any good citizen of the time: he informed the government. (This was the version Elizabeth Longford embraced.)

All the while, error and trickery were hampering attempts to separate the myth from the facts. What apparent evidence was there? For many years, historians cited a line from the London Courier newspaper dated 20 June 1815, two days after the battle and a day before official news of the victory arrived. It stated simply: "Rothschild has made great purchases of stock."

On the face of it, this supported the legend, but there is a problem: those words do not appear in surviving copies of that day's Courier. Instead, it now appears that the purported quotation originated in the writings of a Scottish historian, Archibald Alison, in 1848 – two years after the Satan pamphlet was published.

Further backing for the legend came in the form of an entry in the 1815 diary of a young American visitor to London, James Gallatin. On the day of Waterloo, he writes of great public anxiety over events in Belgium, adding: "They say Monsieur Rothschild has mounted couriers from Brussels to Ostend and a fast clipper ready to sail the moment something is decisive [on the battlefield] one way or the other."

Once again, this is not what it seems. The Gallatin diary was exposed in 1957 as a fake cooked up late in the 19th century – long after the Satan story had gained currency.

The first modern attempt to challenge the myth was made in the 1980s by a Rothschild – Baron Victor, a retired scientist and public servant who wrote a book about his ancestor Nathan. It was Victor who identified the powerful role played by the Satan pamphlet, and he debunked many of the dafter allegations.

But he also discovered in the Rothschild archives a document that muddied the water.This was a letter written to Nathan Rothschild by a bank employee in Paris about a month after Waterloo, and it included the statement: "I am informed by Commissary White you have done well by the early information which you had of the victory gained at Waterloo." Proof, it seemed, that the legend had some foundation in fact. There matters have stood since the 1980s, and in those years the old legend has enjoyed a new lease of life online, while historians and writers have continued to pay it lip service.

But fresh evidence has now surfaced which allows us finally to put this story in its proper context. Newspapers published in the week of Waterloo make it clear that the first person to bring authentic news of the victory at Waterloo to London was not Nathan Rothschild; rather, it was a man who had learnt of it in the Belgian city of Ghent and made a dash to England.

This shadowy figure, identified only as "Mr C of Dover", was telling his story freely in the City from the morning of Wednesday 21 June – at least 12 hours before the official news arrived. It was published in at least three newspapers that afternoon. We also know that a news report written that Wednesday evening referred to Nathan Rothschild receiving a letter from Ghent reporting a victory and passing his news to the government – though this was noted alongside reports of two other, similar letters.

So, while it is confirmed that Rothschild had early news, he was not the only one.

Did Rothschild have time to buy shares? Apparently, but in the thin market of the period, it could not have been enough to accumulate holdings sufficient to earn him the millions that Dairnvaell wrote of. Nor did he manipulate the market to double his gains, for, contrary to legend, there was no slump in prices that Wednesday.

Nathan Rothschild may have "done well" from his purchases when stocks rose sharply following the confirmation of the victory, but his gains were dwarfed by those of numerous rival investors who, without any advantage of early information, had bought key government securities earlier, more cheaply and in quantity.

Two hundred years on from Waterloo, then, not much is left of Satan's tale. It's just possible to see the factual elements upon which a vivid myth was built: Nathan Rothschild did have early information and it seems he did buy shares. But it was only by taking these facts out of their relatively humdrum context and adding a heap of falsehoods on top – relays of horses, storms in the channel, pigeon post, market manipulation – that a narrative of any interest was fashioned.

There is no doubt why that was done: to smear the Rothschilds and Jews generally. Perhaps this bicentenary year of Waterloo would be a good time to recognise that smear for what it is.

Brian Cathcart is professor of journalism at Kingston University London and the author of 'The News from Waterloo' (£16.99, Faber)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments