The legacy of Lockerbie: A good week for conspiracy theorists

What really drove the release of 'bomber' Abdelbaset al-Megrahi? Compassion – or politics and trade deals? Was he even guilty? David Randall investigates

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's a very long time since conspiracy theorists had a week as good as this one.

The saga of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi was already murky enough, but now, to the doubts about the evidence against him, the alleged multi-million payouts to the prime prosecution witness, and the far-from-told story of US and British intelligence involvement, we can add suggestions of secret talks and trade deals, and the possibility that his release was not done in the name of compassionate justice, but that of oil, financial services and hotel-building.

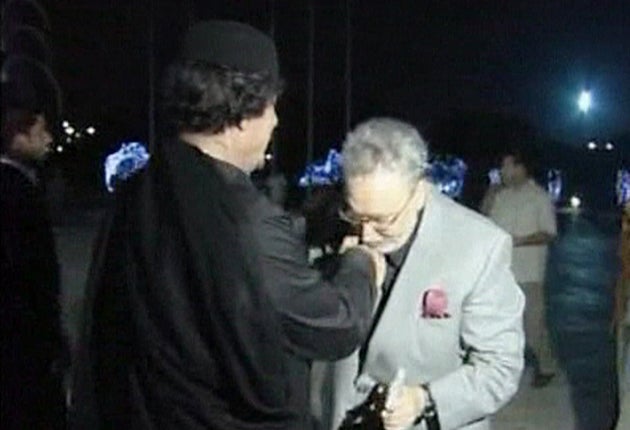

This weekend, suspicious minds don't have to seek very far for the material to construct explanations other than the official ones. There is the meeting in 2007 between Colonel Gaddafi and Tony Blair, then still Prime Minister. Oil and gas deals mingled with the fate of Megrahi (then yet to be diagnosed with cancer), according to the Libyans. There's the meeting between Gaddafi's son and Peter Mandelson in the inevitable setting of a Rothschild villa. The Duke of York, batting for Britain as ever, is involved. There may have been, say some sources, many more meetings between British and Libyan officials – something which, one might think, a simple release on compassionate grounds would not warrant. There are British business leaders now openly rubbing their hands together at the suddenly revitalised opportunity for UK banks, oil interests, security contractors, and stores to move in on Libya's considerable available funds.

And then, underpinning all these, is another conspiracy, the one it all started with – the fact that some group of people somewhere conspired to blow up Pan Am flight 103, and succeeded. Today, 21 years, millions of words of testimony, countless investigations, and a trial on neutral territory under Scottish law later, we are really none the wiser about who murdered Flora Swire, Theodora Cohen, Richard Monetti, Alistair Berkley, Bill Cadman and 265 other victims of Britain's worst terrorist atrocity. And so, given all that is now emerging, doubters of the official line ask: do our governments even want to know who planted the bomb? Do they, perhaps, think that a can of worms is best left unopened in the cause of pacifying former pariah states?

These, then, are the over-heated speculations that have bubbled up in the absence of hard, reliable facts, of which there has always been a shortage in this case. The situation, until last autumn was this: Megrahi, head of security for Libyan Airlines based in Malta, and tied to his country's intelligence services, had been convicted in 2001 on circumstantial evidence of planting the bomb which brought down the American plane over the Scottish village of Lockerbie in December 1988. An appeal was being prepared, and the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission had examined the evidence against Megrahi and found six grounds for a possible miscarriage of justice. The result of this could well have been the release of Megrahi, and avid calls for a re-opening of the case – the 2003 acceptance by Libya of responsibility for the bombing not withstanding.

But Megrahi had been feeling unwell, and in September last year he was taken from HMP Greenock to Inverclyde Royal Hospital for tests. A month later, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Meanwhile, the appeal process ground on, getting into court on 28 April this year in Edinburgh. A day later, a prisoner transfer agreement between the UK and Libya, negotiated by Tony Blair as part of thawing relations between the two countries, came into force. The Libyans duly made an application for Megrahi to be moved to a Libyan jail, thereby handing the hottest of legal potatoes to the Holyrood government.

But as Megrahi's cancer was declared terminal, the Libyan applied for release on compassionate grounds. It fell to the Scottish Justice Secretary, Kenny MacAskill, to decide on this. After representations – including the vehemently opposed ones of US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and leading figures such as Senator John Kerry – he delivered his decision in 20 minutes on Thursday, concluding: "Mr al-Megrahi did not show his victims any comfort or compassion ... But that alone is not a reason for us to deny compassion to him .... Our beliefs dictate that justice be served, but mercy may be shown." So saying, he granted Megrahi's request.

Events moved swiftly. Just hours after Mr MacAskill finished speaking, Megrahi was taken in a van from Greenock Prison to Glasgow Airport, where, wearing a white tracksuit and his face muffled against prying lenses, he crossed the tarmac and boarded his country's Airbus. While he was in the air, preparations were made in Tripoli for his arrival. Busloads of the usual crowd extras were transported to the airfield, DJs played nationalistic songs, and a TV channel controlled by Mr Gaddafi's son got ready to broadcast the homecoming live to the nation.

Meanwhile, President Barack Obama had asked the Libyans not to turn the arrival of this convicted terrorist into a hero's welcome, and, it was later learnt, Gordon Brown had written to Colonel Gaddafi – more in hope than expectation, one assumes – asking the Libyans to show sensitivity.

These requests, contrary to more colourful reports, may have had an effect. Large numbers of welcomers were bussed out again, and the live TV broadcast was cancelled "for technical reasons". So when Megrahi stepped from the plane in a brown suit, aided by a walking stick, the sea of Libyan flags (and one enormous Saltire) was far more modest than it might have been. The President was not there (he left his son to do the honours), and Megrahi was taken to the house his government had provided for his family (complete with video-link screen, so an official from East Renfrewshire Council can check on him twice a month, as per the release conditions).

The reaction from relatives of US victims was unequivocal. Stan Maslowski of New Jersey, whose daughter Diane died on the flight, said: "This shows a terrorist can get away with murder." British families, meanwhile, were mainly supportive of Mr MacAskill. Martin Cadman, whose son Bill died in the bombing, said: "The trial was a farce. I think he was innocent." Anyone puzzled by this difference need look no further than the coverage of the case against Megrahi down the years. In Britain, doubts about the case against him have been long, and widely, aired. In the US, this has not been so. Thus, the extent of the compassion that people were prepared to extend to Megrahi was largely a matter of whether they felt he was guilty or innocent.

The case against him depended on the testimony of one Tony Gauci, a Maltese shop owner who says he sold Megrahi several items of clothing that were subsequently found to have been in the same case as the bomb. Mr Gauci was interviewed no fewer than 23 times by investigators, was alleged to have been coached by them, and subsequently said to have received payments of up to $2m from the US. Some, like former Scottish Lord Advocate Lord Fraser, say he is an unreliable witness ("not the full shilling", and "an apple short of a picnic" were his exact words). Others, such as the leading QC Geoffrey Robertson, are convinced. Describing Megrahi in yesterday's Guardian as "an unrepentant mass murderer", he wrote: "I have read the judgment of the Lockerbie court and the two appeal judgments upholding it, and Megrahi's guilt seems plain beyond reasonable doubt." (Mr Robertson also emphasised Libya's role in supplying explosives to the IRA, something that is the subject of civil proceedings against Libya by lawyers acting for the relatives of 141 people killed by the IRA.)

Naturally, those who take this line also subscribe to the view that Megrahi's release is the result of grubby realpolitik for the sake of lucrative deals and passing diplomacy. The Government's denials (which, even yesterday, were still flowing like water from an unwashered tap) were not overly aided by the news that among those communing with the Libyan leadership was Peter Mandelson. It emerged that the Secretary of State for Business had met Mr Gaddafi's son at a Corfu villa only a week before the announcement that Megrahi could be released. Seif al-Islam Gaddafi, widely seen as the Libyan leader's likely successor, was a fellow guest of the Rothschild family at its Greek property a fortnight ago. Lord Mandelson's spokesman said the case was discussed in "a fleeting conversation about the prisoner". Yesterday, Tony Blair also denied that he had been party to any deals involving the release.

When the business deals start to be signed (as they will, the Colonel's new-found admiration for British justice will see there is a "Megrahi dividend"), there will be plenty who will assume that, because B followed A, it was predicated on it. But already there was much being done, including, for those wishing to smell a rat, Rentokil's contract to reduce Libya's rodent population. And when business starts to rise, suspicious eyes will see shadowy hands at work.

In the short term, a lot depends on Megrahi's illness. There must be many in Edinburgh and Westminster who will, without voicing such thoughts, be hoping his cancer runs its vicious course sooner rather than later. For if he were to survive much beyond three months, there would be many, especially in the US, pointing out that expedience, rather than compassion, was what really tempered British justice.

There is no evidence for such dealings, and so, in all likelihood, we will be left with only one true conspiracy: the one that caused it all – the one that sent 270 people to their deaths on a terrifying December night 21 years ago.

Abdelbaset al-Megrahi: from terrorism to trial – and from prison to freedom

21 December 1988

Pan Am flight 103 is brought down by a bomb, killing all 243 passengers and 16 crew on board as well as 11 people in Lockerbie – a total of 270.

13 November 1991

Abdelbaset al-Megrahi is indicted by both the US Attorney General and the Scottish Lord Advocate. However, Libya refuses to allow the extradition of Megrahi or fellow accused, Al Amin Khalifa Fhimah,pictured far right, instead proposing the trial be held in Libya. This is not accepted by the US or UK. Megrahi and Fhimah are held under house arrest in Tripoli.

20 April 1998

Jim Swire whose daughter Flora died in the Lockerbie bombing, meets Colonel Gaddafi as a spokesman for Lockerbie victims. Gaddafi agrees to hand over two suspects for trial by a Scottish judge in a neutral country.

19 March 1999

Nelson Mandela gets UN permission to fly to Libya and meet Gaddafi. He says the suspects will be handed over on or before 6 April. On 5 April 1999, Megrahi and Fhimah arrive in The Netherlands and are charged. The trial is suspended.

3 May 2000

The trial begins.

31 January 2001

Megrahi is found guilty of the 270 murders. A minimum sentence of 20 years is recommended by judges. Fhimah is acquitted and told he can return home to Libya.

7 February 2001

Megrahi launches an appeal. The appeal hearing begins on 23 January 2002.

14 March 2002

Losing his appeal, Megrahi is flown to a Jail in Glasgow where he begins his sentence.

23 September 2003

Megrahi's lawyers apply to the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission to review the sentence and conviction, arguing a miscarriage of justice. He is granted a second appeal on 28 June 2007.

21 October 2008

Megrahi's lawyers reveal he has been diagnosed with advanced-stage prostate cancer.

14 November 2008

A court rules Megrahi will not be released while he appeals against his conviction.

25 July 2009

Megrahi asks to be released on compassionate grounds. He applies to have his appeal abandoned on 13 August 2009 and his application is approved five days later.

20 August 2009

The Scottish Justice Secretary, Kenny MacAskill, grants Megrahi release on compassionate grounds, after being advised he may have just three months to live. Megrahi arrives in Libya to a hero's welcome, provoking strong criticism from the US and the UK.

A nation divided: Speaking for Scotland

'It was exactly the right decision. I passionately believe that Megrahi had nothing to do with it. He was cynically scapegoated by the Americans.'

Tam Dalyell

Former Linlithgow MP

'Scotland's flag has been seen on TV screens across the world waved by those giving a hero's welcome to a mass murderer. Surely even the most enthusiastic supporter of the SNP government will feel uneasy about this?'

Tom Harris

Labour MP for Glasgow South

'The way that the SNP government has treated this sensitive issue has betrayed a total lack of competence and respect for the families of the victims.'

Tavish Scott

MSP and Scottish Liberal Democrat leader

'Perhaps you'd feel an extra measure of satisfaction or think that justice would be better served if Megrahi died in prison; I'm not sure I do.'

Allan Massie

Journalist and commentator

'Distinguished lawyers have cast such doubts on the reliability of the evidence at Megrahi's trial that we cannot now say whether or not he was guilty. Whether he was the instrument or not, we don't know who ordered the action, or facilitated it.'

Robert Black QC, FRSE

Professor Emeritus of Law, Edinburgh University.

'I will be demanding an enquiry in the Scottish Parliament into the circumstances of Megrahi's imprisonment as well as his release.'

Margo MacDonald

Independent MSP

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments