The Big Question: How has 'chugging' changed charity collecting, and has it got out of hand?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

Research released today has shown that two-thirds of British people would cross the road to escape the attentions of a street collector or "chugger". The poll, by Leap Anywhere, showed that over a quarter of Britons had lied to chuggers, telling them they had already given money to a colleague. It also claims that only one in 10 people like to be approached in the street by a charity collector, with nearly a quarter saying they hate it, as well as saying that one in three Britons are giving less time and money to charity now than they were a year ago.

So what is chugging?

Chuggers or "Charity Muggers" are either the heroic people who brave the worst of the British weather to raise money for good causes or the annoying urchins in fluorescent tabards who accost anyone unfortunate enough to meet their gaze – depending on your point of view. Opinion is divided on the effectiveness and morality of chuggers' work. Some think that pro-active fundraising is an essential tool to keep charities going. Others simply feel embarrassed at being confronted in the street. In either case, one regulatory body found that £54m is generated in new direct debit pledges alone each year. On the other hand, Oxfam gave up using street fundraisers back in 2003, instead preferring to have people on the streets handing out information on the charity.

How is the industry regulated?

While the industry is regulated jointly by the Charity Commission and the Institute of Fundraising, the solicitation of direct debits specifically (which accounts for the vast majority of chugging) is regulated by the Public Fundraising Regulatory Association (PFRA). The Association ensures all its members adhere to the Institute of Fundraising Code of Practice, and monitors how and when public places are used for fundraising. Solicitation of cash, on the other hand, is regulated by local government.

Among other things, the Code says that chuggers must ensure that personal details provided are handled securely and that they must carry and display ID saying they are working for and on whose behalf they are fundraising. It also forbids chuggers from "saying or doing anything that could pressurise or harass people" and from "using manipulative techniques". The PFRA also run quality control of chugging through what it terms as "a nationwide ongoing mystery shopping exercise conducted by an independent organisation". This, it says, consistently returns excellent results, with fundraisers scoring a mean average score of 92 per cent across 26 indicators including "courtesy" and "awareness of regulations".

Certain laws are also applicable. For instance, under new regulations that came in last year under the Charities Act 2006, chuggers are required to state that they are paid and to give an estimation of their employer's remuneration when they ask the potential donor to confirm their regular donation.

What if they break these rules?

The industry is largely self-regulating. But the Fundraising Standards Board has the power to impose sanctions on chuggers who do not comply with the Code of Practice. It can force charities to apologise to the complainant or improve its training to minimise the chance of a similar complaint recurring.

In terms of face-to-face fundraising specifically, the ultimate sanction from PFRA for a breach of the code of practice is withdrawal of access to fundraising sites. This has been used just four times in the past three years. Each time remedial action was taken by the organisation involved.

How much does chugging raise?

According to the PFRA, every year more than half a million people pledge their support to charities through face-to-face fundraisers they meet on the street or greet on their doorstep. According to the PFRA, the average direct debit gift is around £7.30 per month, the vast majority of which are "gift-aided".

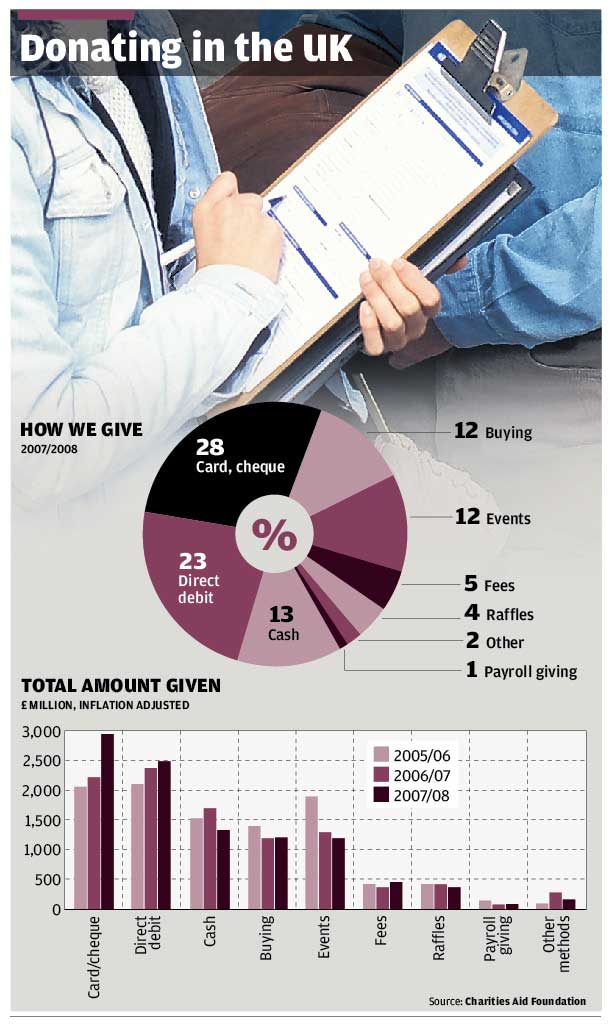

The Association adds that a projected 680,000 donors were recruited in the year to the end of March 2009, up 16 per cent on the previous year. This is the largest number recorded since PFRA began collecting figures in 2003. More than 100 charities are members of the PFRA, including ActionAid, Barnardos and the RSPCA. Donations by direct debit accounted for 23 per cent of all charitable donations in the UK in 2003/04 On any given weekday, there are around 500 chuggers on the streets through the entire UK (including Northern Ireland).

Where do chuggers operate?

Normally known for hunting in packs on high streets, chuggers hit the headlines recently when WH Smith began allowing them into their stores to try to raise money as shoppers browsed. Despite claims that customers would be irritated by the fundraisers, the trial is still going strong, the stationary retailer said.

The areas in which they operate are strictly coordinated by the PFRA. Charities must apply to deploy its fundraisers to avoid having too many in one place at a time.

So why are they controversial?

While some people dislike chuggers simply because they feel they are a nuisance, there have also been reports of fake collectors preying on members of the public. In February, the Irish press reported that a Charities Bill had been proposed to help stop bogus charity collectors. Fine Gael community affairs spokesman Michael Ring said at the time: "I am glad the Government has taken on board my concerns about so-called 'chuggers' who approach people in the street with clipboards seeking bank details for direct debit contributions. There are very many genuine charities whose work is being undermined by fake collectors who mimic their approach and bamboozle the public."

What is the common perception of chuggers?

Despite today's news that most people look to avoid them, the PFRA points out that only 0.6 per cent of people signed up actually go on to make a complaint with the charity. A spokesman added that even that figure may be an over-estimate because it refers to the number of initial complaints and that many of them may therefore, later be dropped. "In our experience, they are often technical complaints as well. 'They spelled my name wrong' for example, rather than a complaint at actually being approached in the street in the first place," he continued. Chuggers do not fare too badly compared to other fundraisers. Research institution nfpSynergy found that when asked which "annoy" them more, only 19 per cent mentioned face-to-face compared with 45 per cent who said telemarketing.

So are chuggers really that unpopular?

Chuggers seem to be more of a minor annoyance than a real nuisance. Mick Aldridge said: "Our quality control officer spends a lot of time observing face-to-face fundraising teams and he doesn't see people zig-zagging across the road all the time. For instance – the figure of 23 per cent 'hating' being approached by a fundraiser: To look at this from the other side, this means that 77-81 per cent of people are amenable to being fundraised to."

So are 'chuggers' a social menace?

Yes...

* If so many people would actually cross the street to avoid them, they must be pretty annoying

* Just because official complaints aren't made doesn't mean they don't get on people's nerves

* People should be free to decide if they want to donate to charity without being ambushed in the street

No...

* Less than a quarter of the population say they 'hate' being approached by chuggers

* They are an essential tool for raising money for good causes, and help maintain charities' profiles

* The number of complaints is so small that they surely can't be that much of a problem

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments