The Big Question: Are equality laws backfiring, with employers reluctant to hire women?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

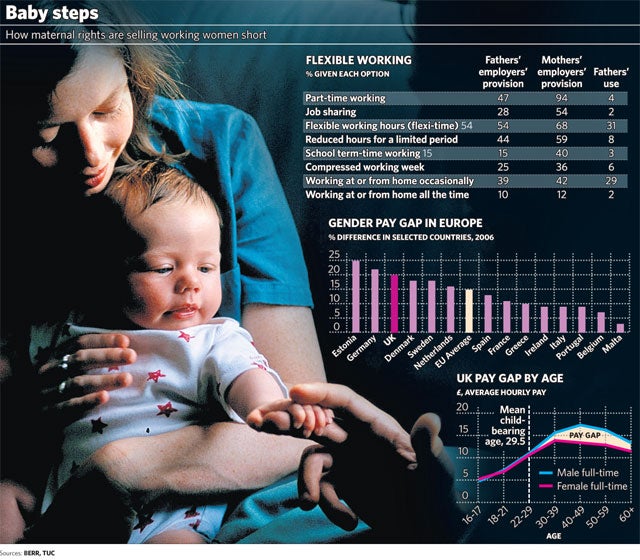

The head of the Equalities and Human Rights Commission, Nicola Brewer, has just announced that recent and future improvements to maternity pay may, ironically, be backfiring on women by making employers wary of hiring and promoting them. The industrial neanderthal Sir Alan Sugar has added fuel to the fire by claiming recently that many employers bin the CVs of women of childbearing age without even considering their job applications.

What is the current provision?

At present women get nine months paid maternity leave, so long as they have been in employment for at least six months. The first few weeks of that, the Statutory Maternity Pay, is paid by the taxpayer, the rest by employers. Companies have to pay the money even if the woman decides not to return to work after the baby is born. The cash cannot be reclaimed by the company from the woman or the tax man. A woman on maternity leave is entitled to any pay rise her colleagues get while she is away. She is also entitled to bonuses or pension contributions that are paid while she's away. If she is sacked for being pregnant or for being on maternity leave, or her promotion prospects or working conditions deteriorate, she can prosecute the company for sex discrimination.

What was it before?

A universal statutory entitlement to 14 weeks of maternity leave and pay was established in 1994. The government of Tony Blair felt that this was not long enough and that it pressurised women, especially those on the lowest pay, to return to work before they or their babies were ready. In 2003, the law was changed to allow fathers to take two weeks' paternity leave with the aim of achieving a better work-life balance for mothers and fathers. In 2007, Labour extended the right to statutory maternity from six to nine months.

What changes are planned?

The nine months is to be extended to 12 months from the end of this year. Statutory Maternity Pay will be extended to 39 weeks. Mothers will get 90 per cent of their usual salary for six weeks and then a reduced rate for a further 33 weeks at a maximum of £112.75 a week. The right of parents to request flexible working hours will be extended until their youngest child reaches 16.

How could this be a bad thing?

Because the changes have created a perverse incentive for employers to discriminate against women. The cost of nine months maternity pay is preventing bosses from giving jobs, or promotions, to women of child-bearing age, many suspect. Increasing numbers of women have been calling the helpline of the Equalities Commission asking for advice on what to do after being sacked while on maternity leave.

The generous provisions, Ms Brewer argues, have reinforced the traditional assumption that children are primarily a mother's responsibility and, indeed, put a brake on changing social attitudes that both parents were equally responsible for caring for their offspring.

Katherine Rake, the director of the equal rights lobby the Fawcett Society, agrees. She recently said that the British system "actively prohibits men from becoming more involved, sidelining a new generation of dads who want to share care. And it means that unscrupulous employers know that it is women, rather than all potential parents, who are likely to take leave, with the result that they can discriminate against them".

Many suspect that the changes in the law have bolstered the existing cycle whereby men climb steadily through professional and management hierarchies while women take time off to look after children and then return to work at lower levels and are told – by men like Sir Alan Sugar – that they then do not have the experience to get promoted.

Who cares what Alan Sugar thinks?

Because it is blokes like him who still, in the main, are the ones who utter the words: "You're hired". And potential employers are reluctant to hire anyone they may suspect will soon be off to start a family – demanding the best part of a year's salary for doing nothing to help the business. Sir Alan believes that "companies have no divine duty to help with child care. Companies employ people. It's the Government's responsibility to provide child care". He thinks employers should be able to ask women about their intentions regarding having children. So long as that is illegal, as it is now, he says, if "you're not allowed to ask [you] just don't employ them".

Why should we pander to dinosaurs like him?

Because he represents an economic reality. For many employers – especially in small businesses – the cost of maternity leave, and hiring and retraining temporary replacement staff, can be prohibitive. In addition, small firms find it difficult to plan their workforce needs if mothers want to return only part time after the baby is born.

The Federation of Small Businesses has called for a "reality check" on parental leave and wants a stop on legislation that is moving "too fast and too furious". Others are introducing more fixed-term contracts so general job security is becoming a thing of the past.

What about women without children?

Many are finding that they are suffering, too. Even those who have decided they never want to have children are regarded by many employers with suspicion if they are of child-bearing age – especially if they are married or in a long-term relationship.

Aren't flexible hours for all the answer?

In theory. In practice, the majority of the one million parents who have made use of flexible hours so far, have been women. The latest legislation allows for the last six months of maternity leave to be transferred to the father if the mother goes back to work earlier. But it will be up to the woman to transfer the leave to the man, rather than it being his right.

Nicola Brewer wants men to be entitled to 12 weeks of leave on 90 per cent of their earnings following the birth of a child – the same as women. At present, British fathers have the most unequal rights in Europe, entitled to only two weeks of leave compared with 52 for mothers. There would be other benefits in encouraging fathers to play a more active role in caring for their small children. In Sweden, fathers who take up to two years off work after the birth of a child are 30 per cent less likely to get divorced. The problem might be getting British men to take the leave.

Is extending maternity leave to one year a good idea?

Yes...

*It would stop women returning to work before they or their babies were ready

*It will provide a better work-life balance for mothers and fathers

*It will particularly help the lowest-paid women

No...

*It will backfire on women by making employers wary of hiring them

*It will sideline a new generation of dads who want to share care

*It will pander to the prejudices of dinosaurs like Sir Alan Sugar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments