The Battle of the Beanfield: The violent new-age traveller clash with police at Stonehenge remembered 30 years on

Police and travellers clashed violently over festival plans at Stonehenge - Richard Jinman speaks to witnesses

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.‘It was a hideous thing, a defining point in my life,” says Dale Vince, a former new-age traveller and owner of the green energy company Ecotricity. “I slept with one eye open after that. It was hard to feel secure.”

He is talking about the Battle of the Beanfield, a clash between a large convoy of travellers and thousands of police that took place near Stonehenge on 1 June 1985. Tomorrow’s 30th anniversary will elicit mixed feelings among those who were there. To some, it was a day of infamy, a violent police ambush in which terrified women and children were attacked by baton-wielding officers who destroyed mobile homes with relish. Others remember it as a successful operation – supported by many in the community – in which police made a stand against an anarchistic subculture that was flouting the law.

In 1985, Mr Vince was a 23-year-old member of the Peace Convoy, a community of about 600 people in 140 vehicles that was determined to stage a free festival at Stonehenge. The authorities had other ideas. Appalled by lawlessness and the open use of drugs at the previous year’s event, the police obtained a High Court injunction preventing the gathering from taking place.

There was no shortage of bad blood between the police and the travellers. “It had been building up for years,” said Martin Meeks, a former Wiltshire Constabulary inspector who believes many of the travellers enjoyed breaking the law. “We never had the numbers to take them on, so they got away with it.”

The two groups met about seven miles from the ancient stones. Mr Vince, who was riding ahead of the convoy on a motorbike, was the first to encounter the police. Rounding a corner he found the road blocked by tons of gravel scattered by three commandeered tipper trucks. For their part, the police were alarmed by the size of the convoy. Realising they were heavily outnumbered, the Wiltshire force called for reinforcements. As the day wore on more than 1,200 officers – including members of the Police Support Unit, a group trained in public order and riot control – were assembled.

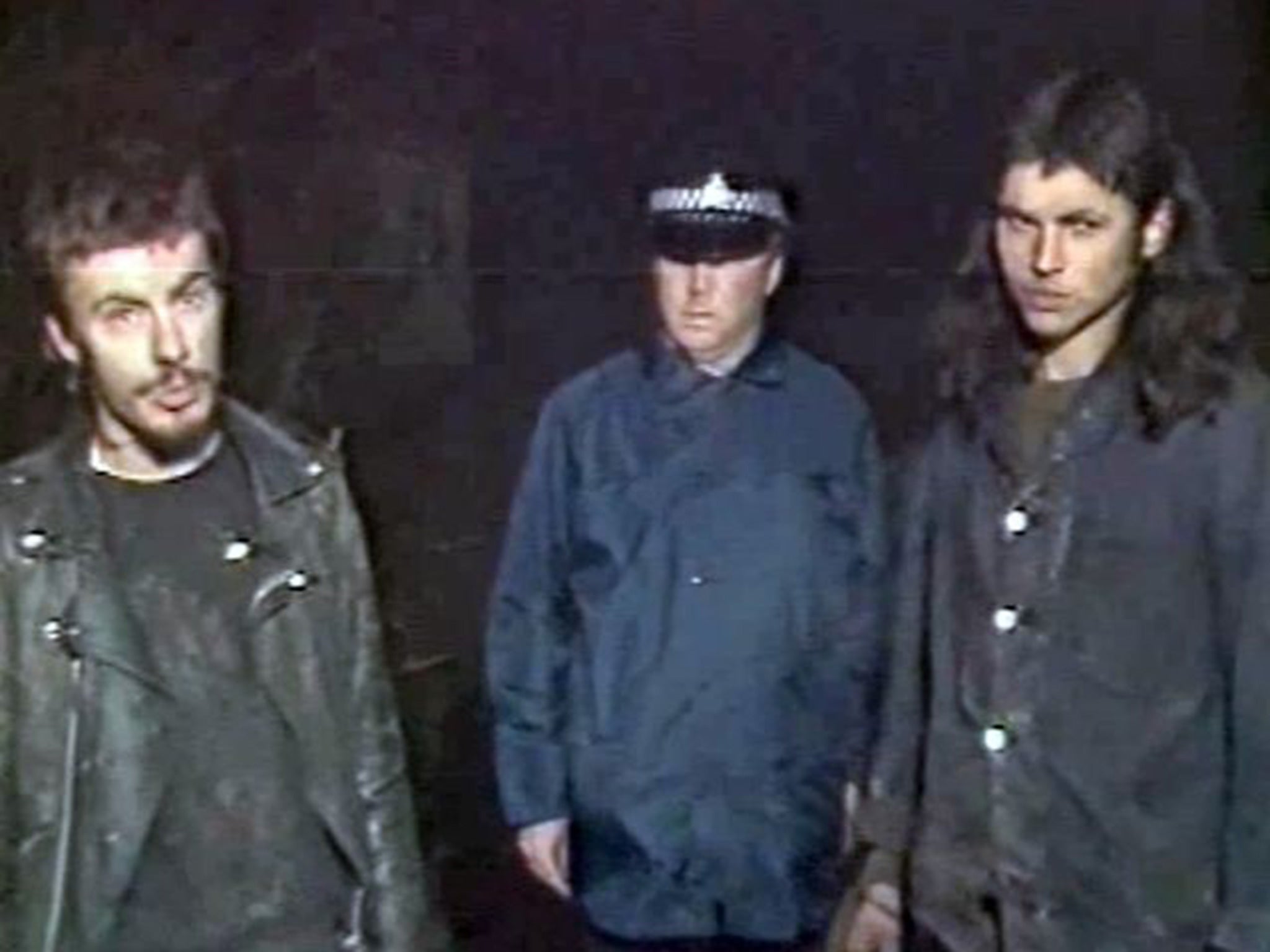

The first clash took place when the convoy ran into the roadblock. Police say the travellers tried to break through by ramming police vehicles. Officers retaliated by smashing the windscreens of several vehicles and making the first arrests. The rest of the convoy broke into a nearby field and the scene was set for a violent confrontation that would result in the largest mass arrest of civilians since the Second World War.

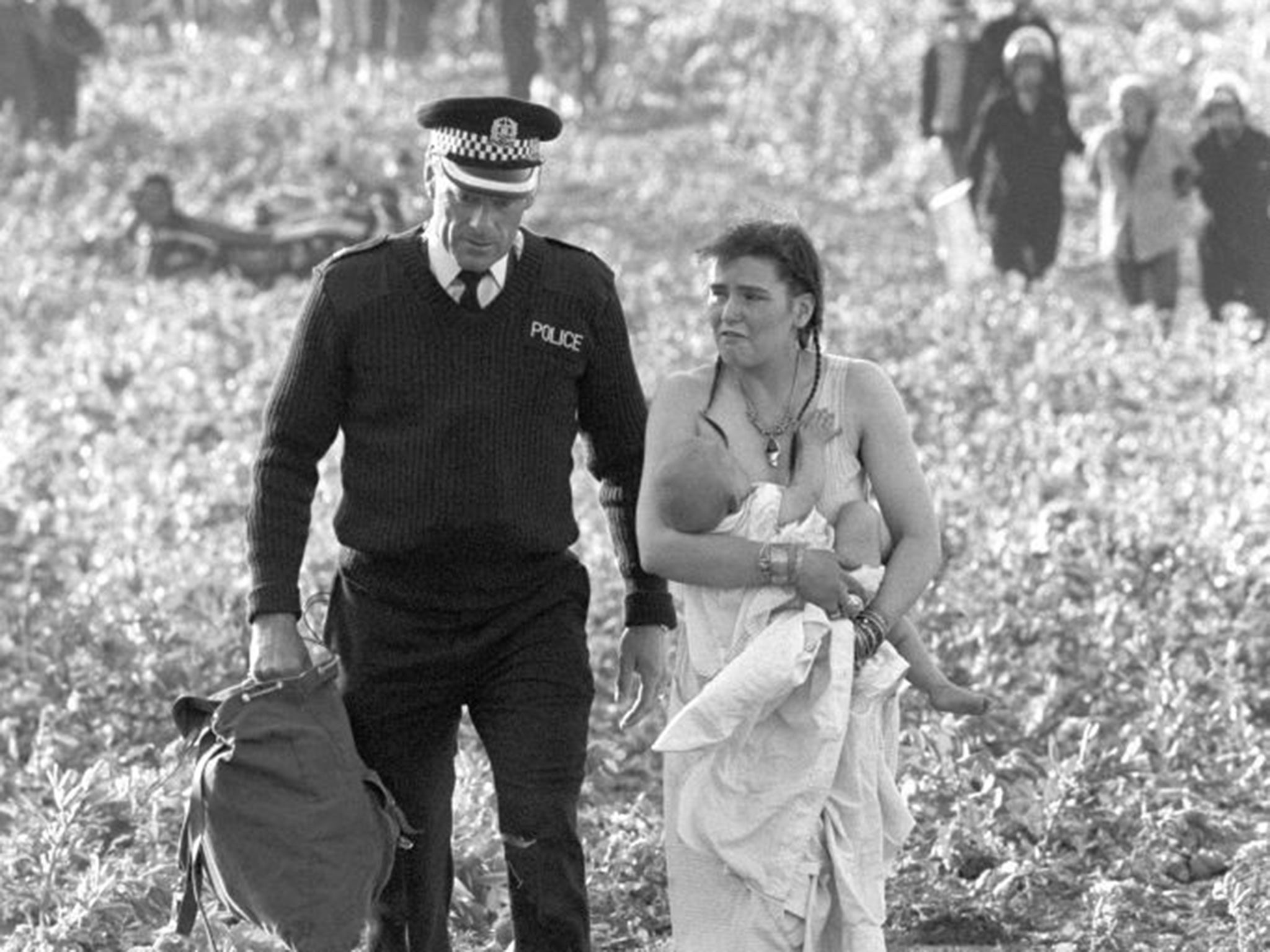

One of the few unaligned witnesses to the “battle” was the Earl of Cardigan, David Brudenell-Bruce. The convoy had camped on his estate the previous night and he followed it, sensing something momentous was about to happen. The earl has vivid memories of what he describes as “the appalling excesses carried out by the police”. He recalls two officers running towards a “very pregnant woman” who had climbed out of a coach. “Both of them clubbed her over the back of the head with their batons until she fell,” he says.

He also witnessed a woman and her baby showered with glass when police threw a “missile” at the windscreen of the vehicle in which she was sitting. “All of this was simply terrible to witness at such very close range,” he says. “But when I sought to write down the identification numbers of some of the worst offenders I saw to my horror and anger that many of the officers in question had their ID covered up.”

The earl makes it clear that “not all the travellers were saints and not all the police were sinners”. There was a “lawless element” within the convoy that threw stones at the police and shouted obscenities. The point, he said, is that you might expect that kind of behaviour from members of the convoy. “You do not expect to see numerous uniformed police officers simply lose their temper and commit criminal acts like smashing the dashboards of abandoned vehicles with hammers.”

At the end of the day, eight police officers and 16 travellers were hospitalised. There were 537 arrests after Donald Smith, the Wiltshire chief constable, swept down in a helicopter and informed the travellers by loudhailer they were all under arrest. No one disagrees the day was chaotic. Buses, vans and cars raced around and the police stopped them in any way they could. Travellers were dragged out of vehicles and missiles flew from both sides. The aftermath was a field of mangled vehicles and bloody faces.

Was the intervention justified or proportionate? David McMullin, who drove a police support vehicle that day, believes it was. “It was a battle of wills,” he said. “They said ‘We’re going to go to Stonehenge and having a free festival’; the chief superintendent said, ‘You’re not.’ Anarchy versus law and order.”

Martin Meeks agrees. He said the travellers were given the chance to turn back and drive away, but they refused. He points out that missiles were hurled at the police and some vehicles tried to run them over. “I don’t think there was any gratuitous violence, but both sides were going to fight to the last man.” That isn’t how Mr Vince sees it. He describes the police as “super aggressive”, adding: “I think they always had a plan to trash the convoy. They were animals. The travellers were a challenge to the established order.”

The clash certainly changed lives. Mr Vince left the country within a year, eager to escape what he calls “a time of police and state persecution”. The Earl of Cardigan gave his account of the day to journalists. His testimony – which he would repeat in Crown Court when 24 travellers sued the police for wrongful arrest, assault and criminal damage – led to him being labelled a “class traitor” by The Daily Telegraph. The police were cleared of wrongful arrest but the travellers were awarded £24,000 for damage to “persons and property”. Both sides claimed victory.

Could it happen today? Superintendent Gavin Williams of Wiltshire Police, asked if the force had misgivings about its past, was diplomatic. “Of course we regret what happened, but … it was considered a legitimate response at the time. There has been a change of culture. This is an era of cooperation and facilitation.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments