Scott of the Antarctic - the last letter: 'Excuse the writing – it's been minus 40'

The full text of the Antarctic explorer's final note to his naval commander is released 101 years after his death

As Scott of the Antarctic stared death in the face, failure was preying on his mind. The polar explorer felt that, should he not return from his 1912 expedition, he had not made proper provision for his wife and two-year-old son – and hoped the nation would look after them.

He feared that posterity would say he was too old to lead a trek into the unexplored Antarctic, and wanted the world to know he could have succeeded if some of the younger men with him had been physically tougher.

The insight into Captain Robert Scott's state of mind just before his death, 101 years ago today, comes from a letter he wrote to his former commanding officer in the Royal Navy, the full text of which was made public for the first time yesterday. It was privately owned for a century but has been bought by the Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge for £78,816.

Scott wrote eight letters as death closed in. In one addressed to the First Sea Lord, Sir Francis Bridgeman, he said: "I want to tell you I am not too old for this job. It was the younger men that went under first."

He added: "I want you to secure a competence for my widow and boy. I leave them very ill provided for but feel the country ought not to neglect them. After all, we are setting a good example to our countrymen, if not by getting into a tight place, by facing it like men when we were there."

Scott was 42 when he set sail from Cardiff for Melbourne in the supply ship Terra Nova in June 1910, hoping that he and his party would be the first humans to set foot on the South Pole. They set up camp on Ross Island in January 1911, having heard while they were in Australia that they were in competition with a Norwegian expedition, led by Roald Amundsen.

The British set off for the pole in October 1911 with sledges, ponies and dogs. The ponies could not cope, and by December they had all been shot. The dog teams turned back in mid-December. Scott and his four remaining companions reached the South Pole on 17 January, only to learn that Amundsen had got there first. A despairing Scott wrote in his diary: "Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward for priority."

Worse followed on the journey back. One of the party, Private Edgar Evans, died on 17 February after a fall. By 15 March, Captain Lawrence Oates had developed severe frostbite and, realising he would hold the others back, told them: "I am going outside and may be some time." He walked out into a blizzard and was never seen again.

Scott, Dr Edward Wilson and Lieutenant Henry Bowers died in their tent only 11 miles from a food depot, having trekked about 800 miles back from the pole. They were found by a search party eight months later.

Until the recent acquisition, the note to Sir Francis was one of two of Scott's last letters in private hands. The other, to Edgar Speyer, was sold last year for £165,000. Letters he wrote to his wife Kathleen, and to Oriana Wilson, Emily Bowers, Sir Reginald Smith and George Egerton, are already held by the institute. The eighth, addressed to Scott's friend, the Peter Pan author JMBarrie, appears to have been lost.

Naomi Boneham, the institute's archivist, said: "It seems fitting that we should be able to announce this major acquisition exactly 101 years after Scott's final diary entry."

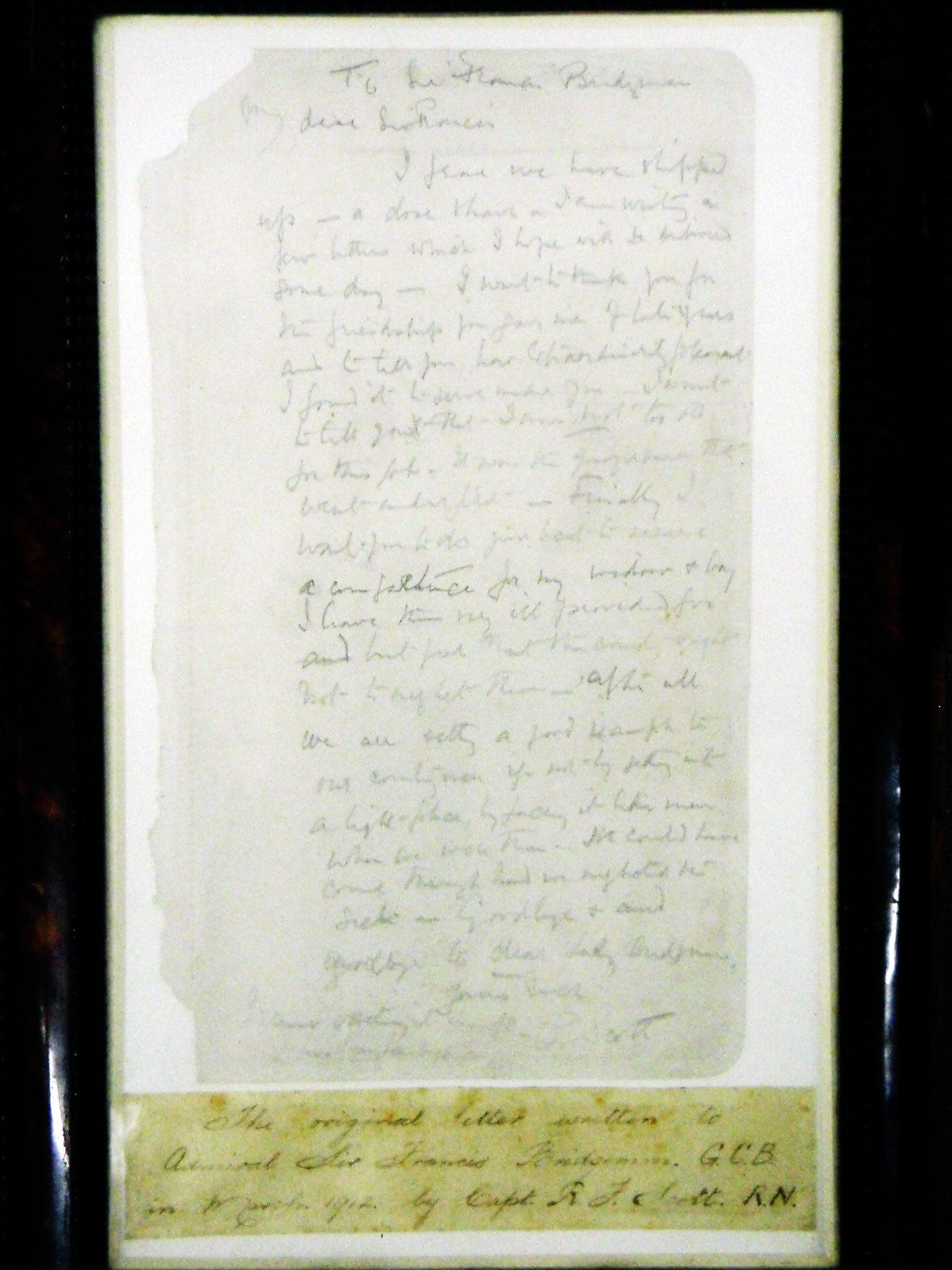

Signing off: Scott's last letter

My dear Sir Francis,

I fear we have shipped up – a close shave. I am writing a few letters which I hope will be delivered some day. I want to thank you for the friendship you gave me of late years, and to tell you how extraordinarily pleasant I found it to serve under you. I want to tell you I was not too old for this job. It was the younger men that went under first.

Finally, I want you to secure a competence for my widow and boy. I leave them very ill provided for, but feel the country ought not to neglect them. After all we are setting a good example to our countrymen, if not by getting into a tight place, by facing it like men when we were there. We could have come through had we neglected the sick. Good-bye and good-bye to dear Lady Bridgeman.

Yours ever, R Scott

Excuse writing – it is minus 40, and has been for nigh a month.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments