Not worth the paper it’s written on: why the Bank wants to put all of its notes on plastic

Under plans to save money, smaller, more durable polymer cash will end 300 years of traditional currency

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The problem of soggy bank notes ruining your laundry after going through the wash cycle could soon come to an end if the Bank of England gets its way. It plans to scrap more than 300 years of history by replacing today's “tatty” paper bank notes with more durable – and smaller – polymer ones.

It’s not out of concern for the nation’s washing that it plans to act: more prosaically, it is proposing the switch to save cash. The move will save the Bank a healthy £100m in a decade.

It will also cut down on fraud, the Bank claims, as plastic cash is harder to counterfeit. And there will be less need to launder money – in the literal sense of the phrase – as polymer notes are more resistant to dirt and moisture and so stay cleaner for longer than paper notes.

The cash saving will come from the fact that the plastic notes will last two-and-a-half times as long as the existing paper ones, which means they are cheaper to produce as they don’t need to be replaced as often.

But while they will survive a washing cycle, or being immersed in red wine, they can be damaged by ironing, as they begin to shrink and melt at temperatures above 120 degrees.

The Bank is also trumpeting about the environmental advantages of longer-lasting notes and the fact that polymer ones can be recycled easily for other plastic items, such as plant pots. But Charlie Bean, deputy governor for monetary policy at the Bank of England, said that any switch would only be made if people wanted it. “Our objective is to supply good-quality, genuine banknotes that command the people’s trust,” he said.

As such, the proposals are currently “under consultation” until 15 November. If there is major public objection, then it says it will back down.

If the plans are accepted the new notes could be with us by 2016, in time to coincide with the new Winston Churchill fivers and Jane Austen tenners. People who have used plastic notes speak favourably of them. Writer Emma Lunn used them on holiday in Australia this year and is a fan. “They’re waterproof which meant you could take money to the beach and keep it in your shorts while swimming,” she said. “In the UK, I suspect they’re more likely to be useful in the rain or if you accidentally put cash through the washing machine.” She added: “They are very hard to rip or tear.” However if they are torn they can then tear easily.

What do the plastic notes feel like? Polymer bank notes are made from a transparent plastic film which is coated with an ink layer which carries design features to make them look similar to the notes we already use.

However, they feel much more slippery to the touch than good old paper ones, and while they are bendy they are not so easy to fold. Meanwhile, keeping a wad in your pocket can lead to them slipping and sliding to the floor when you take them out, according to one visitor to Australia.

The notes will be smaller than before, as well as including a new highly-visible watermark of Britannia, which will mean they will look markedly different to our current notes.

The polymer currency is planned to be around 15 per cent smaller than our current fivers and tenners which sounds like another money-saving idea, but the Bank says the move will make the notes easier to store in wallets and purses.

The experience in other countries has largely been positive. The Reserve Bank of Australia was the first to print a polymer note in 1988 and the country went fully plastic in 1996. Since then 20 countries have followed, including Brunei, Papua New Guinea and Romania.

Canada made the switch while Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England was in charge of its national bank, so it seemed logical he would push through a similar switch here soon after taking control this year. However the Bank says the proposals follow a three year study, which included consulting other countries that have switched to polymer.

Pound for pound: Footnotes

* There are 770 million UK bank notes in circulation.

* The paper is made by a specialist, using cotton fibre and linen rag.

* The watermark design is engraved in wax.

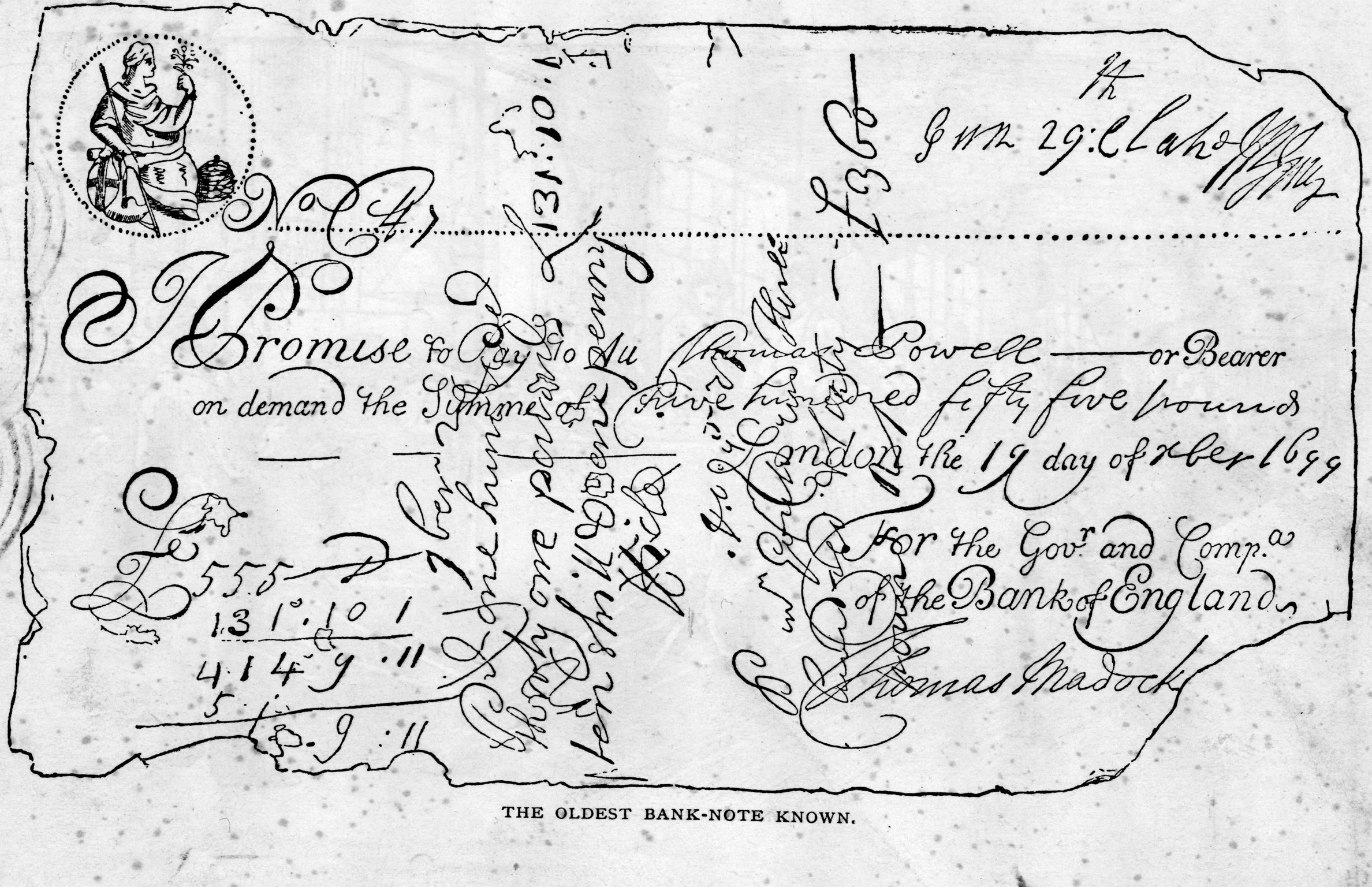

* The Bank of England has issued bank notes since it was founded in 1694.

* All notes are produced by De La Rue Currency in Loughton, Essex.

* The most common note is the £20, followed by the £10.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments