Many women are in low-paid jobs and are far less likely than men to be in charge: ONS study says progress to gender equality at work has stalled in last 20 years

In the 1970s and 1980s, the gender gap at work was closing quickly, but progress has slowed dramatically

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Progress towards a more equal workplace has slowed in the last two decades, according to official figures, which show that women have only been inching forwards since the 1990s.

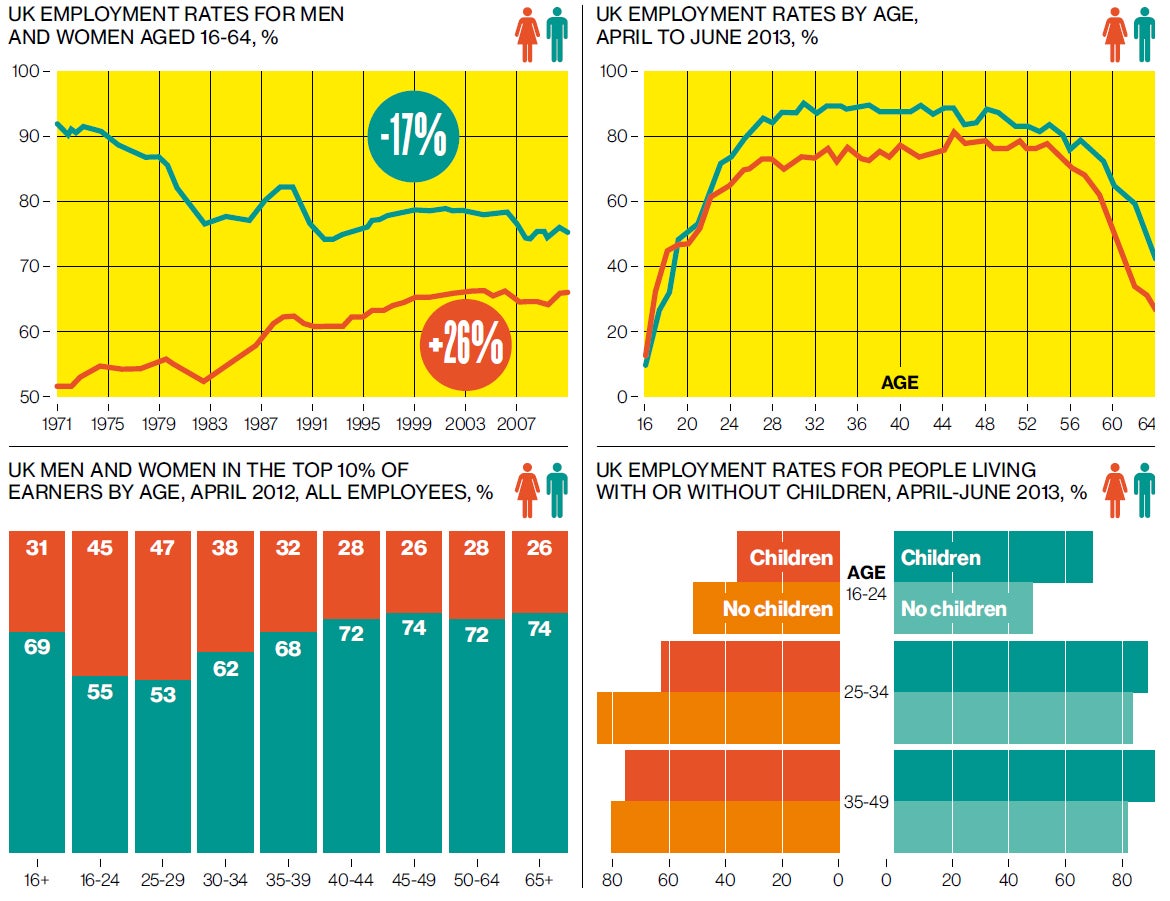

More than two-thirds of women aged 16 to 64 are now in work, compared to just 53 per cent in 1971, according to a study of 40 years of women’s employment by the Office for National Statistics.

This rise has coincided with the number of men employed falling: the proportion of working-age men with jobs has gone from 92 per cent in 1971 to just three-quarters in 2013.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the gender gap at work was closing quickly, but progress has slowed dramatically in the last two decades.

One explanation for this is the rise of the service sector and the decline of manufacturing, which began in the 1960s. Dramatic change was also driven by anti-discrimination legislation in the 1970s, including the equal pay act and the employment protection act, which made it illegal to sack someone for being pregnant.

Though there are now some 13.4 million women aged between 16-64 in work, many are still in low-paid jobs and they are far less likely than men to be in charge, the study found.

One thing which continues to keep mothers out of the workplace – or in poorly paid part-time work – is the prohibitive cost of childcare. Britain’s is now amongst the most expensive in Europe – a situation that prompted Labour to pledge this week that they would increase free childcare for working parents of three and four-year-olds.

Daisy Sands, policy manager at the Fawcett Society, believes the latest figures are further evidence that women still face a “motherhood penalty” at work.

She said: “Women in the UK still tend to do the lion’s share of childcare. Add to this the lack of flexible working opportunities and prohibitively expensive childcare, and we face a situation where, for women, work all too often doesn’t pay.

“This ‘motherhood penalty’ is most keenly illustrated in the nation’s capital – Londoners face the highest costs for childcare in the country, and therefore some of the most expensive in Europe.”

After the age of 22, men are always more likely to be in work than women. This difference becomes even more dramatic if people become parents.

Having a baby makes a man much more likely to be employed and a woman significantly less likely. Between the ages of 25-34, for example, nearly 89 per cent of men with children have jobs, compared to around 83 per cent of those without. Meanwhile, 63 per cent of women of the same age are in work if they have children, compared to 85 per cent who do not.

Diane Elson, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Essex and chair of the Women’s Budget Group, believes the gender gap will not close until the workplace is radically rethought.

“Jobs have not been redesigned, so women are still expected to fit in with a job design based on the idea that the person doing the job has got somebody else at home who will be a mother, a wife, a girlfriend, who will deal with all the issues of childcare and care of the elderly,” she said.

“Jobs have not been redesigned with the idea that men would equally be carrying out these chores.”

There is still a strong gender bias in the types of jobs men and women do. For example, 82 per cent of the caring and leisure workforce are made up of women, compared to a third of managers and senior officials.

More than three-quarters of administrative and secretarial jobs are done by a woman, while just one in 10 work in skilled trades.

Men are more likely to be better-paid and in skilled jobs. This year, 37 per cent of men were employed in the upper-middle skilled roles compared with 18 per cent of women. This is one of the reasons men make up the majority of workers in the top 10 per cent of earners.

Susan Himmelweit, professor of economics at the Open University, believes low pay for women creates a vicious circle, as it makes them less likely to stay in work after having children. She said: “So long as you have a gender pay gap – and these figures show you certainly do – it’s going to be the case that, if you’re in a couple and you’re only going to have one worker, it makes more sense for it to be the man in employment.”

The gap between male and female pay widens with age. Amongst 16 to 29-year-olds, the top 10 per cent of earners is fairly evenly split between men and women. The most dramatic fall in the percentage of these top earners that are women then happens in the 30-34 age groups, coinciding with women having children in their late 20s.

Birmingham has the lowest proportion of women working, with just over 50 per cent employed.

This may be linked to the ethnic diversity of the city, with many families from a culture with more traditional views about women’s roles at home.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments