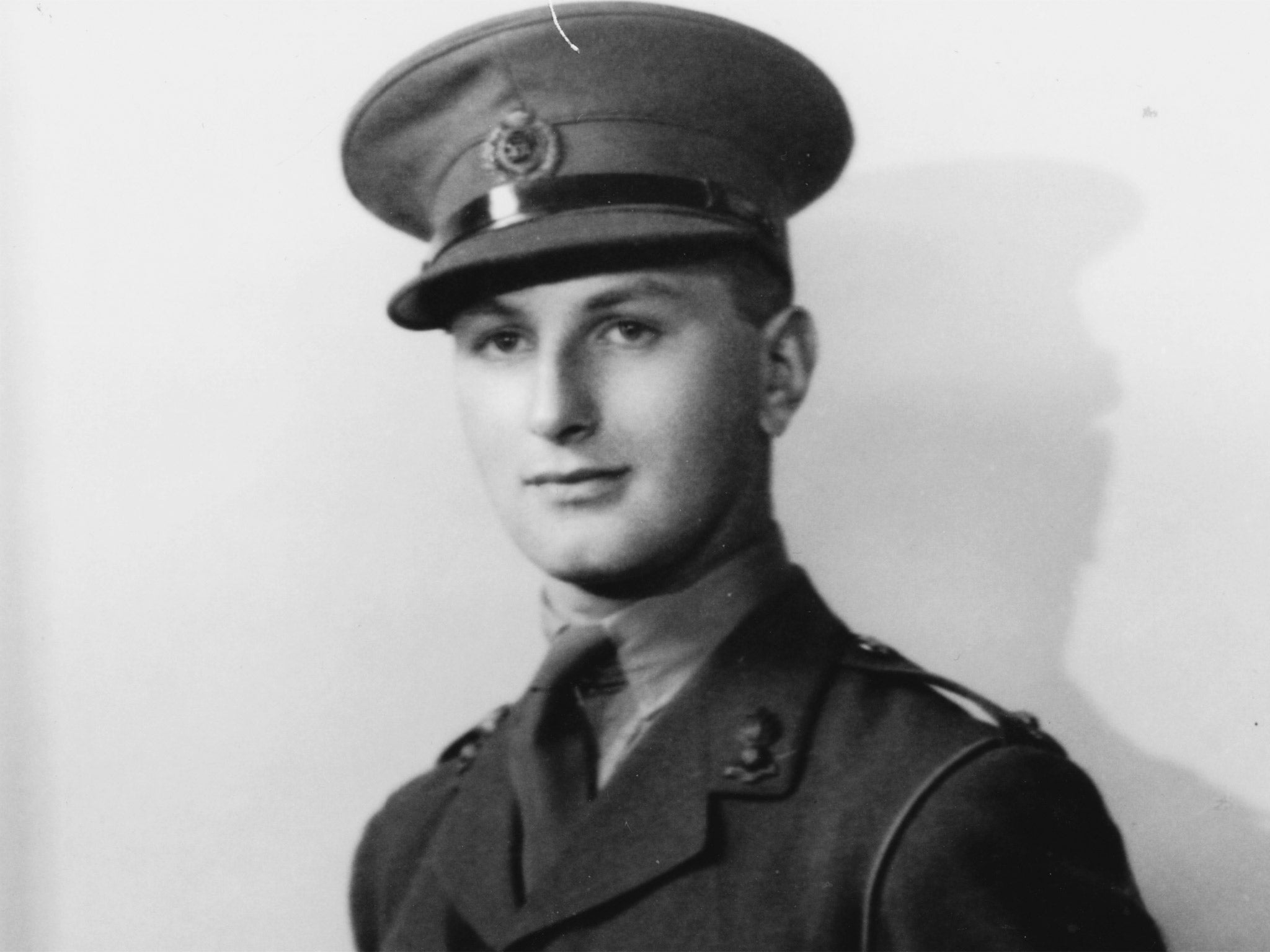

Major Leonard Berney: First British officer to liberate Bergen-Belsen Nazi camp dies aged 95

The 25-year-old Londoner was among the very first from the outside world to enter through the gates of Bergen-Belsen. He died from a heart attack while on the Caribbean island of St Vincent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Shortly before British forces reached the devastation of Bergen-Belsen, a German colonel bearing a white flag crossed the front line to warn the Allies they were approaching a facility holding “civilian political prisoners” in the grip of a typhus epidemic.

When Major Leonard Berney, then a 25-year-old British Army officer, arrived at the gates of the camp three days later on 15 April 1945, he was confronted with the reality of both the abominable lie and the grim truth of the Nazi envoy’s message.

The young Londoner was among the very first from the outside world to enter through the gates of Bergen-Belsen as British troops were greeted by its SS guards, led by the camp commandant Joseph Kramer, who would be later executed for his role in the Holocaust following testimony at the Nuremberg trials from witnesses including Berney himself.

Yesterday, the death of the former British officer was announced by his son, who said his father had died from a heart attack on the Caribbean island of St Vincent, where he had been visiting as one of the few permanent residents on board The World, a private luxury cruise ship.

It was testimony to the lifelong impact of what the 25-year-old soldier saw on that day in April 1945 - and for weeks afterwards - that he only produced his first full written account of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen last year, shortly before his death on Monday at the age of 95.

Kramer and his SS comrades had continued to murder their prisoners until the last moments before the British arrived. As they surrendered, Berney accompanied a lorry equipped with a loudspeaker which inched its way through the half mile-long encampment announcing that it was now under the control of the British Army and its inhabitants - not “political prisoners” but some 60,000 Jews and other victims of the Nazi ideology - were safe.

The major wrote: “I remember being completely shattered. The dead bodies laying beside the road, the starving emaciated prisoners still mostly behind barbed wire, the open mass graves containing hundreds of corpses, the stench, the sheer horror of the place, were indescribable.

“None of us who entered the camp that had any warning of what we were about to see or had ever experienced anything remotely like it before.”

What is The World?

Billed as the planet’s only private “community-at-sea”, The World is an ultra-exclusive cruise ship for passengers who, should they so wish, need never get off.

The vessel, which was launched in 2002, contains 165 residences - ranging from a studio to full apartments - and can carry up to 200 passengers as it makes its way around the globe on an ever-changing itinerary.

Briton Leonard Berney, who took up residence in 2009, was one of a handful who stay on board permanently. The vessel is effectively owned by its wealthy passengers, who decide its route and financing via a committee.

In an interview about the 43,000-tonne ship, Berney said: “I miss virtually nothing about living in a normal house. Everything I want is right here. I can't think of a thing where living in a house would be better than living here. The World is my home.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, such carefree living (with access to a cigar room and six restaurants) does not come cheap - annual costs run at about £210,000 a year.

As the true nature of the Holocaust unfolded before Berney and his colleagues, news of what had been found at Bergen-Belsen began to make its way back to Britain and across the world in harrowing reports such as those by the BBC’s Richard Dimbleby.

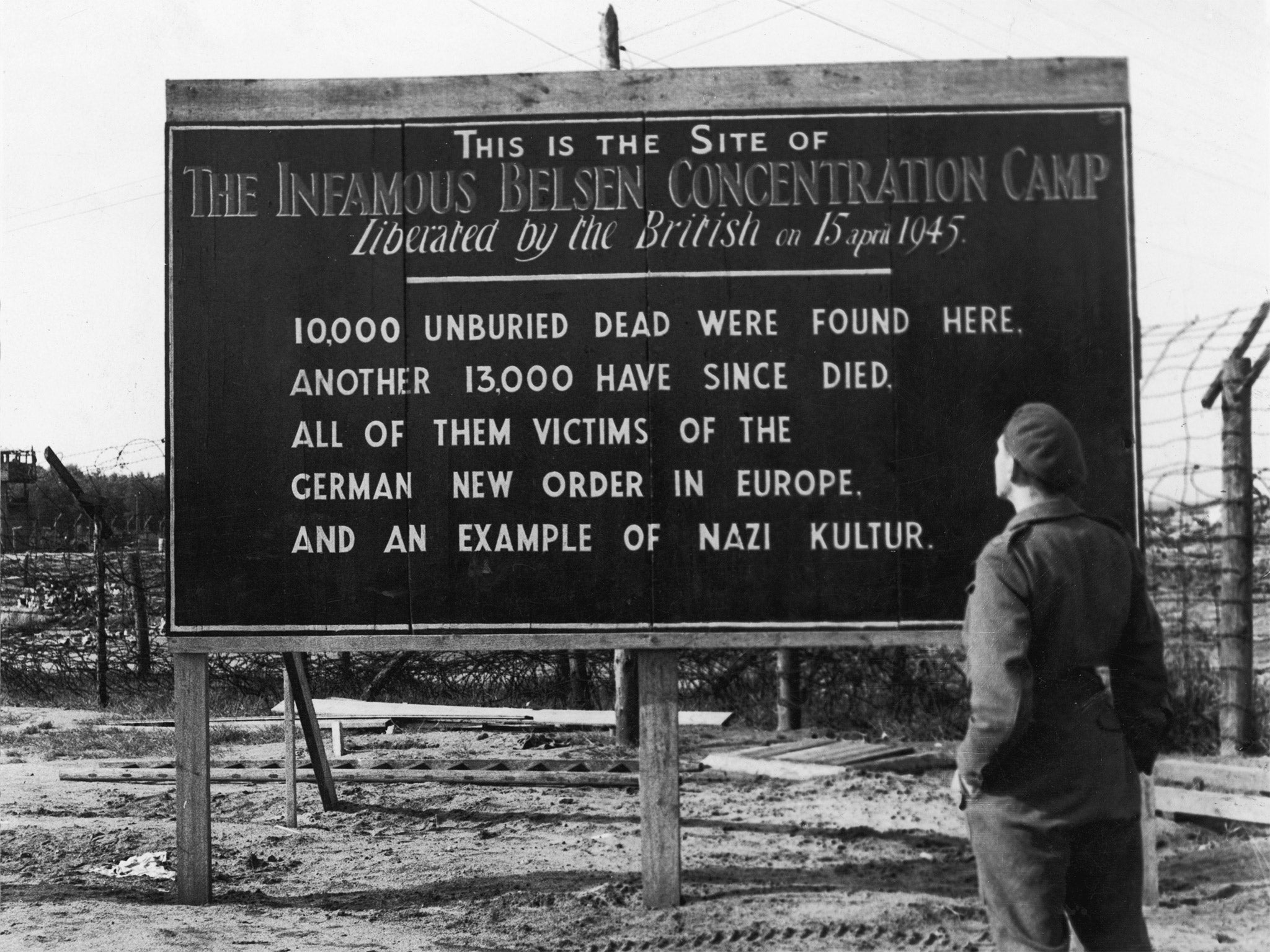

But as revulsion spread across the globe, it was left to Berney and the British forces to come to the aid of thousands of survivors in the grip of what the German colonel had been truthful about - a typhus outbreak killing 500 people a day at the camp near Hanover, central Germany.

Built to house 10,000 people, Bergen-Belsen was not designed as a purpose-built extermination camp like Auschwitz.

But by the end of the war, systematic executions and untreated disease had made it a place of industrialised death all the same. By April 1945, some 50,000 people, among them Anne Frank, had died and the corpses of 13,000 still lay on the ground as the British liberators arrived.

Berney, who had been due to attend Cambridge when war broke out and was regarded by his superiors as a highly capable young officer, spent the day after his arrival getting water supplied to the camp as military doctors began the awful process of triaging prisoners - marking those who might survive with a cross on their forehead.

The following day Berney was sent to find a nearby German Panzer barracks where he found large stocks of food and began the process of turning the site into the world’s largest hospital as beds were set up to treat 15,000 starving and sick prisoners. A lack of understanding of the effects of malnutrition meant that in the urgency to help the detainees by feeding them with normal rations, a number died because their bodies could not cope.

Berney, who remained at the camp for four months helping to supervise its emptying and then burning it to the ground after survivors were moved out, wrote: “The task before us was the like of which nobody had any knowledge or experience… “What SHOULD you do when faced by 60,000 dead, sick and dying people? We were in the army to fight a war and to beat the enemy. What we were suddenly thrust into was beyond anyone's comprehension, let alone a situation which could have been organized and effectively planned for.

“For example, one terrible fact: many hundreds, perhaps thousands, of starving people died BECAUSE we fed them the only food we had, our army rations - who in the circumstances could be level-headed enough to think that out in advance?”

After the war Berney, who was later promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel, went on to a successful business career as a clothing manufacturer, earning enough to buy his own apartment on The World, which continuously circumnavigates the globe at a cost to its 150 passengers of some £210,000 a year. His son, John Wood, said his father had spent the last six years on board and remained in good health until his death on Monday.

Mr Wood said his father had spoken to him of his wartime experiences as a child in the 1970s but had felt prompted to speak out publicly in recent years because of the rise of Holocaust denial.

He told The Independent: “He became very active in the last few years - he could not bear Holocaust deniers. I hadn’t told him but I had begun the process of trying to get him an OBE, gathering supporting letters. It is sad that he never knew but I have a feeling he might have rejected it. He never wanted people to think he was a hero.”

Such humility is challenged by the numbers of Holocaust survivors and their relatives who have come forward to place on record their gratitude to Berney and his comrades for saving their lives.

For his part, the young officer turned entrepreneur retained a sense that it fell to him to communicate the message that the dark events he had witnessed could indeed be repeated.

In a recent interview, he said: “I think the memory will fade, two or three generations on. In the meantime, I’m doing what I can, and others are doing what they can, to educate the young people about what can happen, what did happen and what can happen again.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments