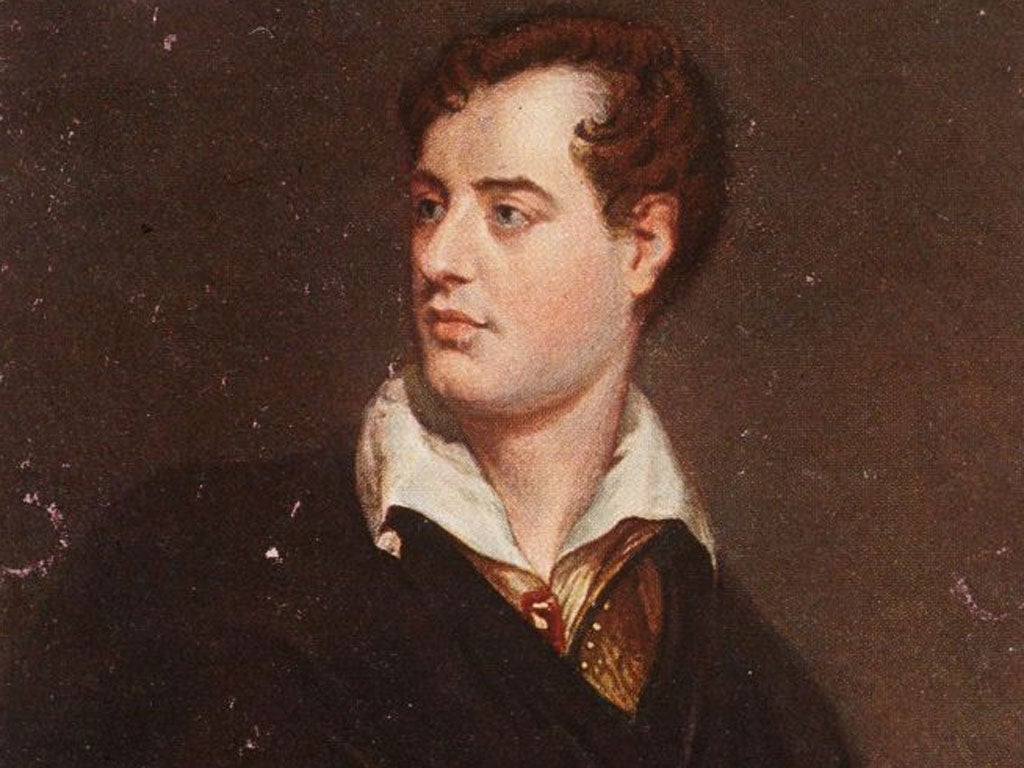

Byron’s brutal takedown of wife and mother-in-law revealed in unseen letter giving insight into burnt memoir

The poet’s manuscript was destroyed after he died amid fears of damage to his reputation

Lord Byron’s brutal takedown of his wife and mother-in-law has been revealed in a newly discovered letter that provides fresh insight into his burnt memoirs.

The poet, who was 36 when he died in 1824, had left his memoirs with instructions to publish them following his death – but the manuscript was burned at the office of his publisher after he died amid fears of damage to his reputation.

Now, a letter that describes Byron’s destroyed memoirs has been found by archivist Adam Green, who was cataloguing the Dawson Turner archive, in Trinity College’s Wren Library at the University of Cambridge.

Elizabeth Palgrave writes to her father, the banker Dawson Turner, that she saw the manuscript on a visit to the publishing house of John Murray, expressing her shock at Byron’s “degrading” of his wife and “aversion” to his mother-in-law.

In the letter dated 29 October 1823, she wrote: “I opened the pages accidentally at that part of his Lordship’s life which mentions his marriage [to Anne Milbanke], and I read it with the utmost interest and avidity.

“Lord Byron prefaces this portion of his manuscript by professing his design of hurrying over it, as it is of all the most painful to record.

“He then, in the most cold-blooded and heartless manner, declares his little attachment to his wife at any time…

“It is grievous to read his declaration of indifference to his wife and of aversion to her mother, whom he never mentions but by the most opprobrious epithets.

“Nor does he ever call his wife by any name but that of ‘Miss Milbanke’.”

She wrote that Byron’s memoirs “contain the most severe remarks, not only on [his father-in-law] Sir Ralph Milbanke’s family, mode of life – but all the families in the neighbourhood whom his Lordship met, are mentioned by name and classed in the wittiest but most cruel manner”.

Ms Palgrave continued: “Lord Byron evidently set his mind to evil – he takes delight in recording his own wickedness, and in the most perverted of all feelings – that of exposing and degrading his wife.

“A leading trait in his memoirs is the extreme pleasure he takes in levelling, as far as he can, those who are eminent for virtue to his own standard.”

Cambridge scholar Dr Corin Throsby said the discovery of the letter was “truly exciting”.

“For centuries people have wondered what Byron’s lost memoirs might have contained, so it is truly exciting to have another first-hand account from someone who read them,” she said.

“Byron was always out to shock, and he would have been unsurprised and possibly delighted by Elizabeth’s extreme reaction to his work.

“Her letter shows the success of Byron’s ‘bad boy’ persona as she is not only disturbed but also clearly fascinated by him, repeatedly imagining how he was feeling while writing.

“In this way, the letter offers a window into how Byron was read in his time and demonstrates the lost memoir’s apparent ability to simultaneously scandalise and captivate its readers’ imagination.”

Byron was a student at Trinity College between 1805 and 1807.

Trinity College archivist Adam Green, who discovered the letter, said: “This fascinating detail is typical of Elizabeth Palgrave’s letters, which burst with intelligence and information.

“It’s typical too of the discoveries waiting to be made in the many relatively unexplored collections of letters – particularly those of women – in this library and elsewhere.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies