‘I’m worried sick’: Hundreds of vulnerable people waiting months to join relatives they depend on in UK

‘He was so happy to be coming to live with us – now he’s in a worsening condition,’ says Syed Hussain of his younger brother, Fahad, who has been told he cannot come to Britain despite having been granted a visa

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Syed and Fahad Hussain live 3,800 miles apart, but the brothers speak on the phone at least five times a day. “I’m trying all day to keep talking to him,” says Syed, 32, a British national living in Hayes, west London. “I’m very scared that he could take any step – even end his life or something.”

Fahad, 34 suffers from severe depression and anxiety. He lives alone in Karachi, Pakistan, and relies on money transfers from his brother and his wife, Agnieszka Tabaczyńska, a Polish national, to survive.

Racist abuse Fahad experienced while studying and working in Austria for five years sent him into a spiral of depression, according to his brother. He returned to Pakistan in 2019 and – with no close family around him, their mother living with Syed in London – has since struggled to cope.

In October 2020, Fahad applied for an EEA family permit visa via Ms Tabaczyńska which, in accordance with EU regulations, before 30 June 2021, allowed extended family members of EU nationals to join them in the UK. His application was initially refused, but in May of this year, the Home Office informed them that the decision had been overturned and the visa granted.

The brothers were thrilled. Fahad started packing his bags and Syed’s young children started getting excited about what they would do with their uncle once he arrived.

But they waited and waited for Fahad’s visa to arrive, and heard nothing. It wasn’t until 15 July – two months later – that Fahad received an email from the Home Office stating that his document was “no longer valid for travel” because this visa route had ended on 30 June.

“It was a horrible moment. Suddenly everything changed,” Syed says. “He was so happy to be coming to live with us – now he’s in a worsening condition. He is very depressed. He has no hope.”

Fahad is one of hundreds of people whom the Home Office has barred from entering the UK in recent months, despite previously stating that they had the right to join their loved ones under an EEA family permit. They all applied long before the visa route was due to end, but faced long delays in receiving the visa and were told shortly after the deadline that they could no longer have it.

I can’t explain how many nights I’ve lost sleep over this. I thought there was a rule of law in this country

When contacted by The Independent this week, the Home Office said these individuals would instead be issued with an EU Settlement Scheme family permit, which it said would enable them to come to the UK. But lawyers say the applicants themselves have yet to receive any information about this, months after being told they can no longer come to Britain.

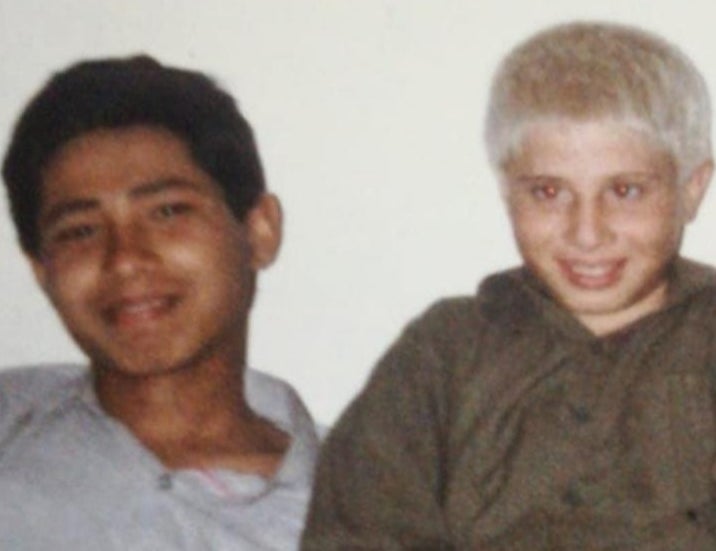

In another case, Ahsan Saddiqui, 45, an albino Pakistani man, was over the moon when his application to join his UK-based brother, Mubasher Begum, a Spanish national, was accepted in February 2021. The application had previously been rejected on the basis that the Home Office did not accept that they were brothers, but on appeal the judge ordered that he be granted the visa.

However, they waited for months and the visa didn’t arrive. In July, he finally received a letter from the Home Office apologising for the delay, but stating that although they had won their case on appeal and the visa was issued in May, it could not be printed until now “due to an error”. As 30 June had passed, it said he was no longer eligible for the visa.

“Life in Pakistan is very difficult for me. I’m albino. I feel discriminated by my society due to the way I look. I have to dye my hair to try to not stand out,” says Ahsan, who has been relying on money transfers from his brother due to the difficulties he faces finding work in Lahore.

Mubasher, 51, who moved to the UK in 2015 after living in Spain, says he was incredulous that the Home Office was preventing Ahsan from joining him in Britain despite the court ruling in their favour. “I can’t explain how many nights I’ve lost sleep over this,” says the taxi driver in Manchester. “I thought there was a rule of law in this country.”

Mala Savjani, solicitor for Here for Good, based at Wilsons Solicitors LLP, who is representing 20 applicants, including Ashan, to judicially review their cases, said denying these family members entry to the UK after agreeing to issue the permits months before was “deeply dishonest”.

“Having spoken to other legal professionals in the sector, it seems likely that there are hundreds of affected applicants,” she said. “This long-term separation combined with the Home Office repeatedly moving the goal posts is having a profound psychological and emotional impact on almost all of these clients, some of whom are children.”

Hassan Shafiq, 25, was informed in February 2021 that his two younger siblings – aged 22 and 15 and living in Lahore – had been accepted for EEA family permit visas. But they did not receive them in time, and were informed in July that they could not come to the UK.

“They are kids and there’s been no one to look after them,” says the Nottingham resident, explaining that when his mother applied for the same visa in 2019 she was granted one after two weeks, and moved to the UK. “They’ve waited a long time. This will have a long-term effect on them.”

Luke Piper, head of policy at campaign group the3million, is aware of hundreds of people who had been separated from their loved ones for many months and, since the route closed in June, had been cut off from getting to the UK.

“We are hoping the Home Office will present a solution that works for everyone caught in this desperate situation, not least because it appears to breach the UK’s obligations under the [EU] withdrawal agreement,” he says.

An Iraqi man living in London, who did not wish to be named, said that his sister, who currently lives in Sulaymaniyah, in Iraqi Kurdistan, was “devastated” after discovering that she and her son would not be able to join him in the UK, despite having been accepted for an EEA family permit months ago.

“Her situation is really bad,” says the man, whose Bulgarian wife sponsored the application. “She lost her other son, he drowned when he was only 16, five years ago. It caused the whole family to break down. Her husband became addicted to alcohol and left her. It’s been terrible.

“We were so happy, trying to get the place set up – but all of a sudden everything has changed. We won the case – they should be here with us by now.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments