Ex-Territorial Army Captain whose critical book on Helmand was blocked by the MoD is finally cleared to publish

Dr Mike Martin criticised the British military for devastating whole areas and killing high numbers of civilians

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A former Army Captain who resigned his commission so he could publish a highly critical book of military involvement in Afghanistan has said ignorant and aggressive tactics which saw towns and villages flattened meant locals quickly came to hate the British more than the Taliban.

Dr Mike Martin said it took three years from their deployment to Helmand in May 2006 for British forces to finally move away from attacks and airstrikes that left areas “devastated” with high civilian casualties. He also criticised the Army for being completely unaware of the historical animosity felt by the local population towards their former colonial masters.

Dr Martin had been locked in a battle with the Ministry of Defence to publish his study after it commissioned him to write a PhD thesis on the recent history of Helmand. Completed in February 2013, the author assumed it had been publicly available at King’s College Library ever since, but a librarian confirmed it has never received the work and the thesis is currently unavailable to the public.

In his thesis, Dr Martin, 31, a fluent Pashto speaker who spent 15 months on tour in Afghanistan and several years researching the book in Helmand and the UK, said the public was often fed a different narrative to what was happening on the ground – as were the soldiers. He said the British were entering a situation already “spiralling out of control” when they officially took over Helmand from US forces on 1 May 2006, and were ill-informed on arrival.

He wrote: “The British knew that they had come to Helmand to support the government and fight the Taliban, but did not have enough knowledge about Helmand’s private sphere to understand exactly who the ‘government’ were and who the ‘Taliban’ were.”

Dr Martin said the Army was oblivious to the historical animosity felt by the local population towards their former colonial masters who assumed that the British wanted payback for the Anglo-Afghan wars of the 1840s. He said this view was encouraged by the aggressive tactics which left areas decimated.

“When they deployed to the north, the communities had no knowledge of why there were British soldiers arriving in their villages and the British had no idea as to who their friends or enemies were,” he wrote in his thesis. “These factors combined with no evidence of reconstruction and very heavy use of airpower to defend their isolated positions resulting in civilian casualties. For example, the British dropped 18,000lbs of explosive (say, 25 airstrikes) on Now Zad that summer and flattened the bazaar.

“Thus, from the perspective of the population, the British public narrative did not match their actions... By this point the Helmandis were 28 years into their conflict and there was no patience for a historical enemy.”

Civilian deaths in Afghanistan from US and Nato airstrikes nearly tripled from 2006 to 2007, with deadly strikes exacerbating the problem and fuelling a public backlash, Human Rights Watch said in a report the following year which also condemned the Taliban’s use of “human shields”. Overall civilian casualty figures vary with at least 10,000 killed between 2006 and 2011 before the figure finally reduced year-on-year in 2012. The war has cost 448 British lives to date.

Dr Martin compares the British operation to clear Now Zad in early 2007 “once and for all” to a Soviet operation from 1988. He said: “The town was reported as ‘utterly devastated’ after British troops attacked and then blew up compounds that they had been fired at from - somewhat different from the reconstruction mission that they had promised publicly.”

Referring to the “massive clear operations” the British engaged in throughout the winter of 2006/7, Dr Martin said: “The operations were not linked to any political objectives apart from killing ‘Taliban’, much like the Soviet operations. The main difference was that the Soviets did very strong political work through Khad (Afghanistan’s main security and intelligence agency), which was entirely absent during the early British period.”

British tactics soon turned the population against them. Dr Martin wrote: “The ‘police’ (militiamen of the warlords) began to leave or switch sides - even though they were loathed by the population, they hated the British more.”

Dr Martin said when he arrived in Nad-e Ali as a Territorial Army Officer in December 2008 he received “no information” about what Helmandis thought in private. He said: “We operated as per the public sphere: that the ‘Taliban’ had taken over the district.”

Only from 2009 onwards did the British finally change and improve their tactics albeit with the help of 2,000 redeployed US Marines, according to Dr Martin. He said: “[The British] began to attempt to operate in a different way, with less violence and a greater focus on the reconstruction that comprised their public narrative.”

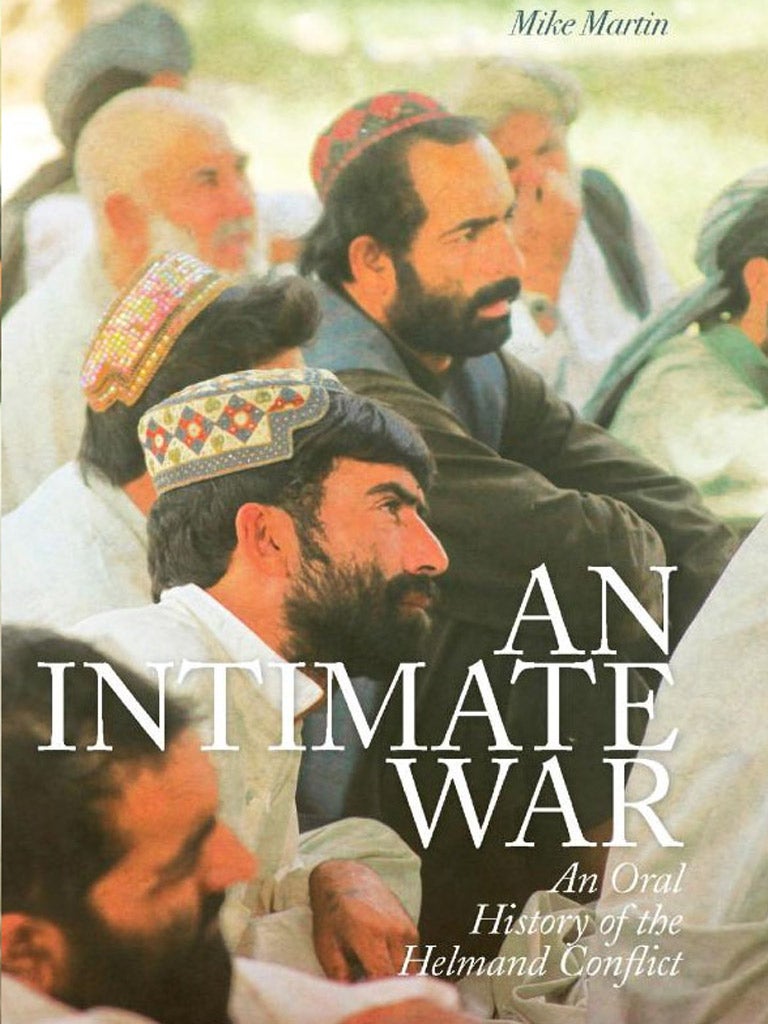

The author wanted to turn his thesis into a book which his Commanding Officer blocked due to its critical content. In an email seen by The Independent, warning Dr Martin not to go ahead with publication of An Intimate War – An Oral History of the Helmand Conflict 1978-2012, the officer writes: “As a Captain in the Army Reserves you are bound by Service Discipline through Military Law while on duty and subject to Army General Administrative Instructions at all times.”

Dr Martin resigned his commission on Monday giving the academic publisher Hurst freedom to publish in May. A spokesman for the MoD said it respected his decision and now had no objection to publication.

Dr Martin told The Independent on Wednesday: “It’s rare that you ever read in the British press news of Afghan civilian casualties, which wasn’t necessarily the fault of the media. Up until 2009 there was an indiscriminate use of force. Because of British involvement, a whole lot of people are dead who would otherwise not have been. There was a definite improvement after 2009 when the MoD put more resources into the conflict. They did try, but I don’t think they tried hard enough.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments