Dunblane will feel Sandy Hook shootings more than anywhere

James Cusick reported on a town in grief and shock after the 1996 primary school shootings

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The outpouring of grief that has come from Newtown, Connecticut, over the past two days will have been understood nowhere more acutely than in the Perthshire town of Dunblane.

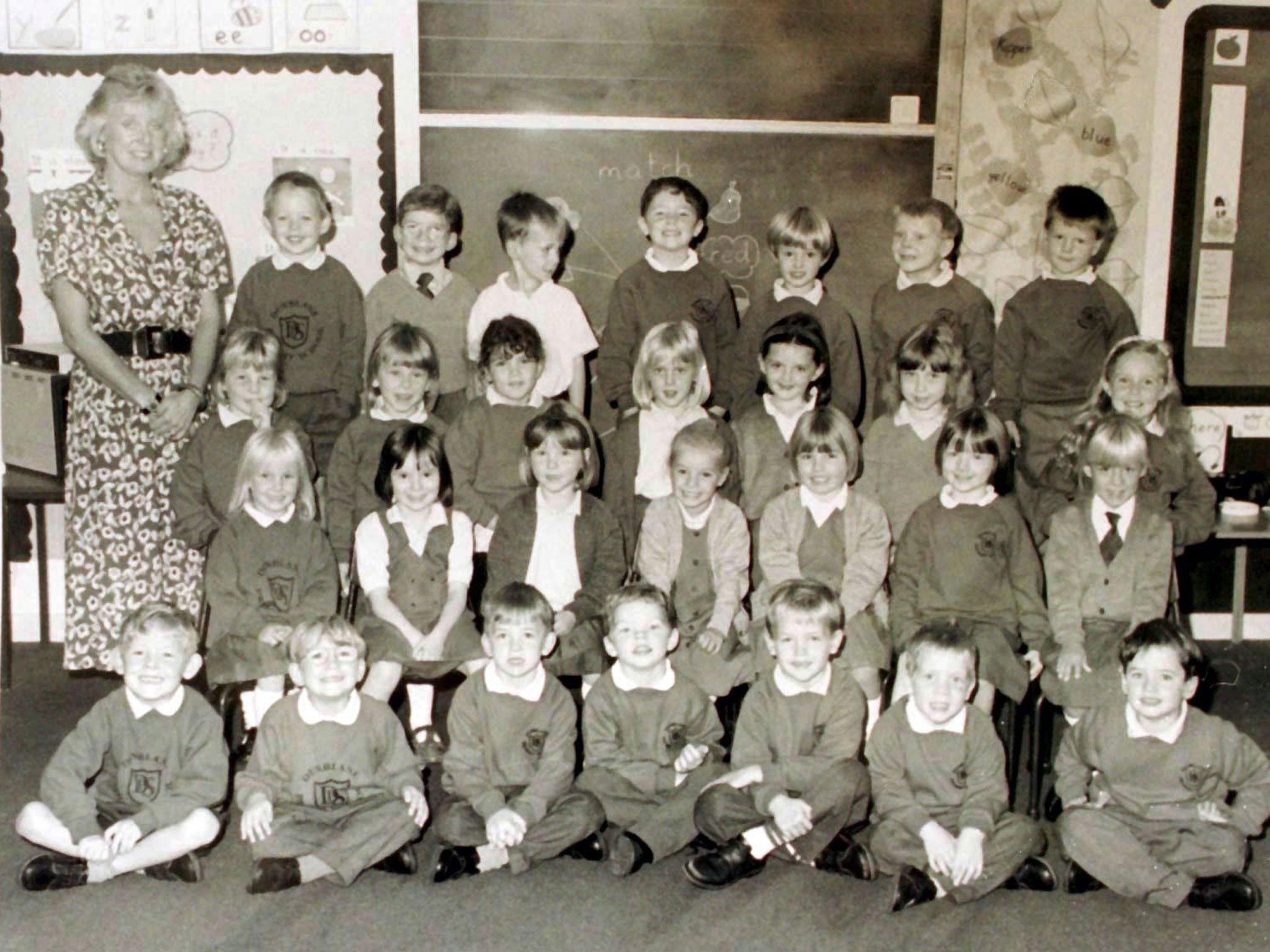

In March 1996, on a bitterly cold spring morning, a cluster of parents waved goodbye to their children at the gates of Dunblane Primary School. For many parents whose children in the infant class were scheduled to have a gym lesson that day, it would be the last time they saw their sons and daughters alive.

The man holding the guns that day – the equivalent of Adam Lanza at Sandy Hook Elementary School – was Thomas Hamilton. He took the lives of 16 children and their class teacher, and was later found dead, lying in a pool of blood in the corner of the school gymnasium. He had killed himself.

The Dunblane community knew Hamilton. He had been a Scout leader who had lost his status as a man trusted to be in charge of children. Closer investigations suggested a paedophile, a fantasist, who had lost control of a self-created world in which he photographed boys in youth clubs.

Hamilton's ultimate motivation is still the subject of debate. But on the day I was part of the army of arriving reporters – though plague might have been the collective term that was used – answers as to why this had happened to an innocent classroom of infants were not the town's immediate priority.

The cathedral city gathered what strength it could and created a cocoon around the families who had lost a child. Their objective was survival – and many reporters, without Lord Leveson in the background, left them alone.

It took days before anyone could speak to you without a tear running down their face, or without telling you how close their own child had come to walking across Hamilton's path on the day the town still struggles to forget. For others, whose family may not have suffered loss, it was still bad: some believed they could have stopped the killer by complaining about him; they never did.

Reports from the United States suggest the townsfolk of Newtown are going through the same horrors. Those who say they knew Adam Lanza, but admit to noticing little beyond a quiet nerd, or a friendless loner, appear to be asking themselves why they didn't press the panic button.

Beyond the media circus that will have encircled this small Connecticut community, the immediate concern of the town – just as in Scotland in 1996 – is to protect the 20 families who have lost young children, and to console the relatives of adults who also lost their lives. The deeper debates on gun control, on why Lanza acted as he did, and how the town recovers normality, may have already started. But for those still trying to hold back tears, these are not their first preoccupations.

I was privileged to watch the parents of Dunblane and report how their grief turned into a political determination that no other family should go through the same suffering. Westminster initially avoided the questions left by the Dunblane shooting, but ultimately the change in Britain's gun laws came from the campaigns launched from the families themselves.

If America needs to ask itself what should happen next, it will begin to find the answers in two places: the small cemetery in Dunblane that holds the graves of half of 1996's class P1, and its US counterpart in Newtown.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments