Drone racing: Teenagers are being lured away from screens and outside to fly their aircraft against each other

Is it a bird? Is it a plan? No, a whole new career!

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Luke Bannister is a 15-year-old schoolboy with dreams of becoming a pilot. A drone pilot that is, a job that didn’t exist as recently as 10 years ago.

It seems certain that he will achieve his goal. Ask anyone in the tight-knit drone racing community and they will tell you that the teenager from Somerset is already an accomplished – some would say prodigiously gifted – aviator.

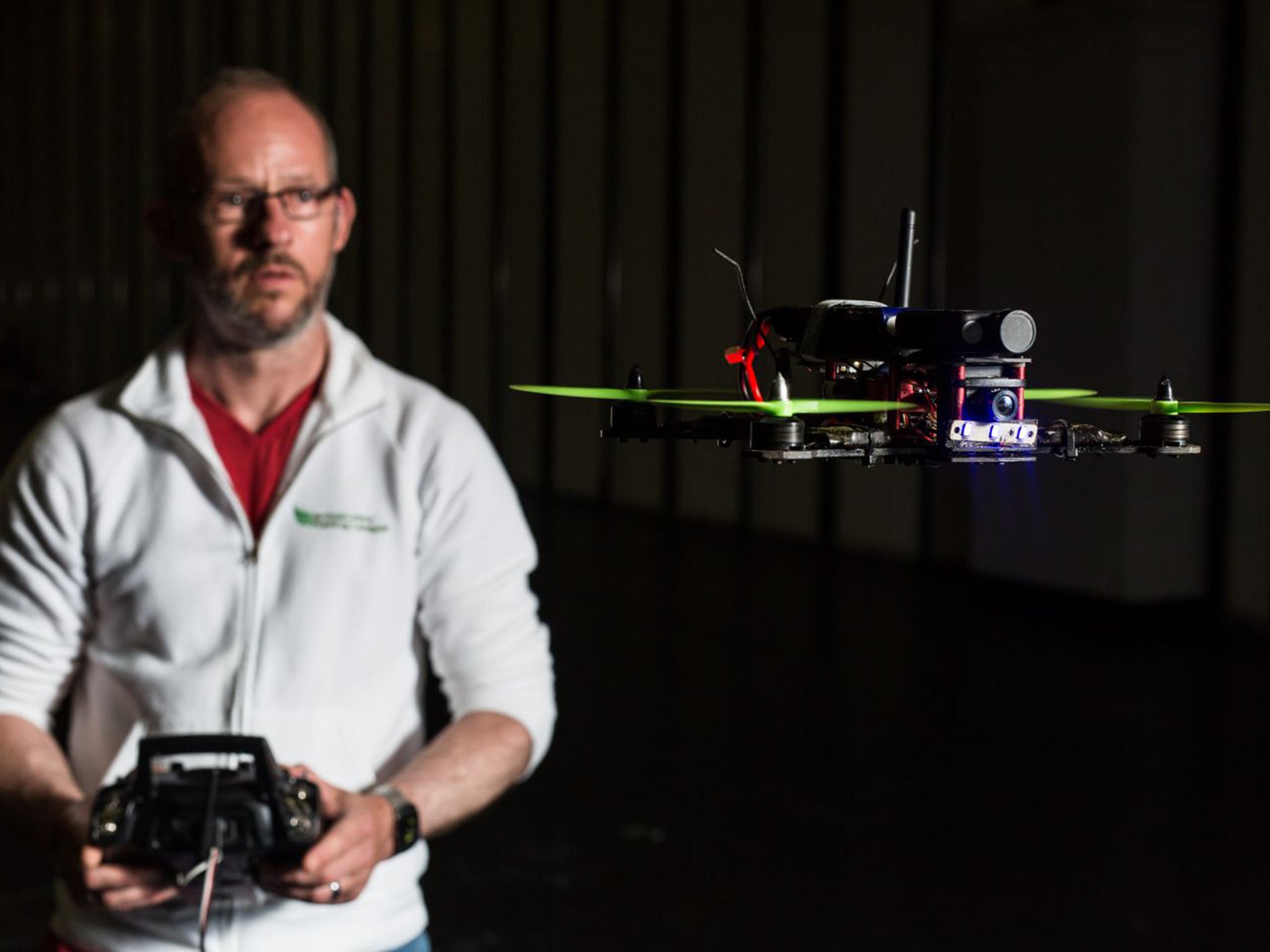

Luke flies a type of aircraft known as an FPV racing drone. FPV stands for First Person View, and refers to the video signal streamed from a camera mounted on the front of the lightweight aircraft to the goggles worn by flyers.

FPV drones are manoeuvred using a conventional radio control transmitter, but the video feed gives the pilot the hair-curling sensation of sitting in the cockpit as the aircraft hurtles through the air at speeds of up to 70mph.

What does that feel like, exactly? Complete freedom, says Luke, who began flying drones just over a year ago. “I love the fact that you can just turn up and be like a bird. You can go exactly where you like.”

Last week, the talented teenager was putting a quadcopter (four propellers) and hexacopter (six) through their paces at a racing track constructed inside one of the halls at the Birmingham NEC. The UK’s first Drone Show will be held here on 5 and 6 December, and a demonstration of FPV racing is expected to be one of the big attractions.

These are heady days for a sport that was still an underground pastime six months ago, says Nigel Tomlinson, the chairman of the FPV Racing League. Formed in January, it has already signed up eight clubs, and another five are in the process of joining. Races are run over a variety of terrain including woodland, derelict buildings and open fields. One club – Bury Metro Model Flying Club – has recently secured what is believed to be the UK’s first purpose-made FPV drone-racing site on an area of scrubland and woodland in a park about four miles north of Manchester.

“FPV racing has been around for about five years, but in the past couple of months it has just exploded,” says Mr Tomlinson. He admits the UK scene has some way to go to catch up with those in the United States, Australia and New Zealand, but the momentum is enormous. The League hopes to stage the first British championships before Christmas and Luke is thought to have a chance of clinching the title.

“He’s just very, very good,” says Mr Tomlinson. “What he can do with a quadcopter is jaw dropping.”

The burgeoning popularity of FPV racing isn’t hard to understand. The sensation of flight – the closest thing to real flying without leaving the ground, as one drone-racing devotee puts it – can be yours for a couple of hundred pounds (and, of course, a lot of practice).

A standard 250mm FPV racing drone, a radio transmitter and a pair of video goggles cost about £250. You can spend a whole lot more, but flashy gear is unlikely to give you an edge on the track because there are strict rules regulating the power of the electric motors, the capacity of batteries and the size of propellers. Crashes are not uncommon, but are seldom terminal.

The drone’s carbon fibre fuselage is resilient, and when they do hit the ground or each other – British racers eschew the time trials favoured by overseas clubs, arguing they would rather race each other than a stop watch – it tends to be one or more of the tiny plastic rotors that are destroyed, and they cost just a few pounds for a full set.

“The spectators love the crashes,” says Mr Tomlinson. “It’s all part of the fun.”

The idea of a projectile with four or six rotors flying at 70mph a few feet above the ground may sound alarming, and the stomach-flipping flight videos posted on YouTube by FPV luminaries such as Luke and James Bowles (aka Jab1a) do little to allay such fears. But everyone involved in the sport is at pains to point out that safety comes first.

The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), the body that regulates drones in the UK, has been supportive, establishing a discrete set of rules for FPV racers. While the larger, heavier drones used by, for example, film companies, must remain within sight of their operator at all times, FPV pilots, by definition, can’t actually see their drone when it’s in the air.

As a result, the CAA stipulates that FPV operators must be accompanied by a “spotter” who maintains visual contact with the aircraft at all times. The CAA’s rules also stipulate that FPV drones are allowed to fly a maximum of 1,000ft (305 metres) in any direction.

“We fully recognise that unmanned aircraft have great recreational and commercial potential,” said a spokesman for the CAA. “And we have no intention of over-regulating the sector.”

“However, operators have to keep within the rules to ensure the industry can develop safely.”

Luke’s mother, Karen, is fully supportive of her son’s passion for drone racing. He got his first piloting experience by playing flight simulator games on a home computer; drone racing, says Karen, is far more active and social than sitting in front of a bedroom PC.

While it’s true that Luke is fixated on the screen inside his goggles for the six to eight minutes it takes for a drone’s batteries to run down, at least he’s (mostly) outdoors and interacting with fellow enthusiasts. “This gets him out of the bedroom,” says Karen. “And there’s no jealousy or rivalry in the league – it’s incredibly friendly and supportive.”

Fancy yourself as a drone racer? Mr Tomlinson says it takes the average rookie “a couple of weeks” to learn to fly an FPV drone. Within a “couple of months” you could beracing. “I’m not saying you’re going to get anywhere ...” he cautions.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments