Church in the lurch

The great and good of Anglicanism are in York for what could be the most explosive General Synod for centuries. Paul Vallely explains the issues that are at stake

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Big words are being thrown around in the Church of England these days; words such as schism, with echoes from 1,000 years ago when the world divided between Rome and the Orthodox; words such as Reformation, with echoes of the split between Catholic and Protestant, which spilt a deal of English blood in the 16th century.

Some 1,333 vicars and other clerics have written to the Archbishops of Canterbury and York threatening to leave the church if its General Synod presses ahead this weekend with the idea of women bishops.

Ho-hum, says the rest of society, for whom gender and sexuality equality has become an unquestioning desideratum, if not an always practised norm, over the past decades. For those with a secularist world view such debates have become a yawning irrelevance. But the air is febrile with a sense of history in the church and for reasons which are not always immediately apparent to outsiders. Women and gays have become its totems.

This weekend's meeting comes hard on the heels of a gathering of 300 conservative bishops and archbishops in Jerusalem, which they infelicitously named Gafcon. It announced the creation of a new grouping of Anglicans which does not recognise the authority of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

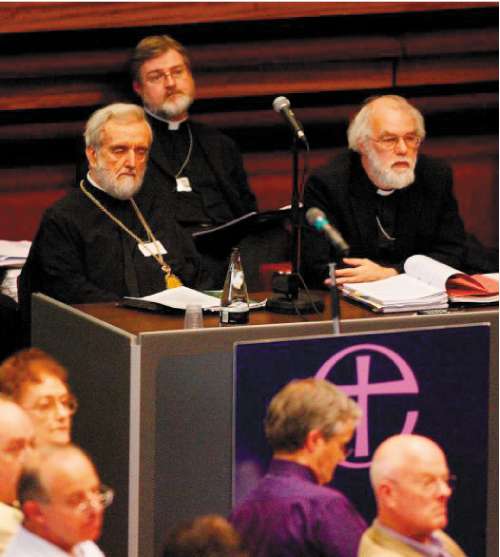

Poor old Rowan Williams, they decided, was part of the spiritual vacuum which has sent the Western world into a spiral of moral decline. In his place, they have set up a new Primates Council and written their own orotund declaration of faith.

Attitudes are hardening. In two weeks, the rest of the bishops of the Anglican Communion will meet in Canterbury for the Lambeth Conference of Bishops, the once-a-decade meeting of high-ranking clergy from around the world to discuss the situation. It will be a nodal point.

Since the crisis began – triggered by the consecration of a non-celibate gay, Gene Robinson, as a bishop in the United States in 2003 – Rowan Williams has made a succession of compromises to conservative evangelicals to avoid a split in the church. But with the setting up of the alternative structures by Gafcon his tone has changed. He has allowed his exasperation to become public, and questioned the legitimacy and authority of the rebels.

His fellow senior bishops have been even more robust. The Bishop of Southwark, Dr Tom Butler, described the dissidents as militant fundamentalists whose manifesto read like something drawn up by a student union during the era of Marxist revolution. It was, he said, "nonsense". And the conservative Bishop of Durham, Dr Tom Wright – whom the Gafcon-ites had hoped would attend their Jerusalem gathering – described their action as "deeply offensive" and a form of "bullying".

It would be easy to dismiss all this internal bickering in a club with a declining membership. But there are 77 million Anglicans across the globe, a number which, in contrast to steadily falling numbers of churchgoers in the UK, is elsewhere growing rapidly. It has an important role in a world gripped by violent religious fundamentalism in which good religion is a far more effective tool to combat bad religion than a disdainful or dismissive secularism.

And it matters to us as a nation because, as a report by the Von Hügel Institute recently demonstrated, the charitable work quietly performed by the Church of England's volunteers – in job-creation projects, urban regeneration programmes, aid agencies, eco-initiatives, youth clubs and with the homeless, the bereaved and asylum-seekers – saves the nation hundreds of millions of pounds. Home Office statistics show regular churchgoers are 48 per cent more likely to do such work than their secular counterparts.

But the debate between the religion of the present and the past is not couched in such terms. Its language is that of theology and social justice. "The argument for women bishops," says Christina Rees, of Women and the Church, who is a member of the Synod meeting in York today, "is simply that God created men and women equal".

Equal but different, says Rod Thomas, of the conservative evangelical group, Reform. "Our understanding of the Bible is that there is equality but also a divinely ordered difference that [St] Paul says goes back right to the Creation, showing the different ways God wants us to respond to him, leading and guiding but also submitting to his will."

Then there are the Anglo-Catholics who insist that the C of E is only part of a church which includes Rome and the Orthodox. They quote the Vatican's Cardinal Kasper, who has warned that "realistically" the move to women bishops will "institutionalise schism" and end the possibility of unity.

Finally, there are the liberals, epitomised by Dr Giles Fraser, president of a group called Inclusive Church (which includes gay priests among others), who insists on contextualising unchanging faith principles in a changing world.

"If you read the Bible as a whole rather than just quoting selective bits, it tells the story of how at the beginning God was thought to be there just for a narrow band, the Chosen People, and it then shows how God gradually breaks down that narrow understanding to reveal that he is there for everyone; the idea that only men can represent God cuts against the whole of the Bible story."

For all that, the rows about the role of women and the inclusion of practising gays do not run along the exact same faultlines. "Women bishops is an issue of church order not a gospel issue," says Rod Thomas. "Homosexuality is about sin and what keeps people from God. Women is therefore a secondary issue." Nor are those who question women bishops automatically uncomfortable with women priests. "When women became priests it was possible for a male vicar not to have that impinge upon him," he says. "It didn't compromise his theology about male headship in the church. But a woman bishop does."

The battle on women priests is now well-won. Last year, for the first time, more women than men were ordained. Nearly a quarter of C of E priests – more than 2,000 – are women. They work everywhere from the smallest parishes to the largest cathedral and serve as chaplains in schools, universities, hospitals, prisons and the armed forces. They include two deans, nine archdeacons and 18 cathedral canons. "Women priests have brought a certain warmth and approachability to the priesthood," says Christina Rees. "They share more, delegate more, and show a greater willingness to collaborate."

In fact, the battle over women bishops has largely been won too. A third of the provinces of the Anglican Communion – including several who attend the Gafcon conference – have voted for women as bishops. In Canada, New Zealand and the United States, women have been elected to the episcopate for several years.

In the Church of England, the General Synod endorsed the principle of women bishops years back. What the present row is about is the measures the church will introduce to provide for those who wish to remain in the Church of England but who say they cannot, on grounds of conviction, accept this development.

Three options are before the meeting. The one endorsed by the House of Bishops, which its critics describe as a "like it or lump it" option, proposes the change be introduced with a code of conduct on how to accommodate the conservative dissenters. It would abolish the practice of "flying bishops" introduced when women were first ordained in 1994 to minister to opponents of women priests. The other clear proposal is for "non-geographical" dioceses to minister to such priests and parishes. Opponents say they would be a church within a church.

In between is a middle option, with four variants, for complex relationships with "complementary bishops" to work within the existing structure. This is the option which no faction prefers but which might be agreed.

"Those who disagree with women bishops are only a small minority but they make a lot of noise," says Christina Rees, who favours the bishops' recommendation. "They are a very small tail wagging a very big dog." Only 2 per cent of parishes ever asked for flying bishops, she says, and only 7 per cent said they weren't prepared to have a woman as their next vicar.

Anglo-Catholics have threatened to leave in large numbers. "We're trying to find a way to stay in, not to leave," says Canon David Holding, leader of the catholic group opposed to females in the episcopacy. He wants a separate non-geographical diocese for dissenters. "It's the only option that will give us adequate protection; [the middle-way option with] all the variations will be incredibly complicated to implement."

The liberals are dead set against that. "The non-geographical diocese would be a bridgehead for a Gafconite takeover," says Dr Giles Fraser. The conference in Jerusalem has made the liberals far less likely to concede that option. Gafcon's closing statement may have insisted that it was not a breakaway from the Anglican Communion, nor an attempt to take over its institutions by hardliners who think the CofE ought to be out there campaigning to convert British Muslims. But many liberals just do not believe them. "You can dress an elephant in a tutu and insist that it's a ballerina," one liberal blogger said, "but it still poops big and eats peanuts."

The changing face of the Church of England

*About 1.7 million people a month will attend at least one Church of England service.

*Between 1968 and 2004, regular weekly attendance at Church of England services fell by 44 per cent (although the decline has now been arrested).

*Nearly a quarter of Church of England priests – more than 2,000 – are women.

*They include two deans, nine archdeacons and 18 cathedral canons.

*Last year, for the first time, more women than men were ordained.

*The average age of male parish priests is 54.

*29 per cent of churchgoers are 65 or over.

*Since 1968, a 10th of Anglican churches in England have been made redundant.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments