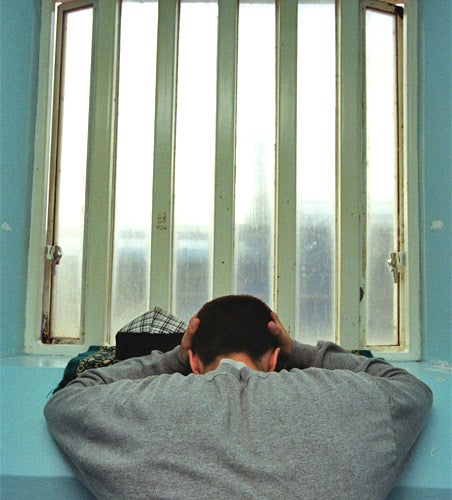

Broadmoor patient makes history with court appeal

Man locked up for 23 years to have detention case heard in public

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A patient in Broadmoor Hospital who has spent more than two decades alongside some of Britain's most dangerous criminals has won the right to have a review into his detention heard in public, The Independent has learned.

The decision, which is thought to be a legal first, has major implications for the way Mental Health Tribunals function and will open the doors to one of the country's most secretive arbitration systems.

The man, who cannot be named for legal reasons, has spent 23 years detained under the Mental Health Act, mostly at Broadmoor Hospital, the high-security facility in Berkshire that houses notorious offenders such as the serial killers Peter Sutcliffe and Robert Napper. He was committed in September 1986 after being convicted on two counts of attempted wounding. Doctors had classified the 52-year-old as having a mental illness and psychopathic disorder, but in September 2008 they changed the diagnosis to just a psychopathic disorder.

Seven months later, the man began a campaign to win his freedom and applied to have a public hearing at the Mental Health Tribunal, which decides whether mentally ill patients can be released. Such tribunals are usually heard in private because they contain details of a person's medical records. Until now, even if a patient was willing to waive their right to privacy, the hearings were still held behind closed doors. But in a judgment handed down on 17 February, three upper-tribunal judges ruled that the case should be heard in open court. Broadmoor and West London Mental Health Trust fought the application, arguing a public hearing would be prohibitively expensive. But the judges, led by Senior President of Tribunals Lord Justice Carnwath, said: "The European Convention on Human Rights requires that a person should have the same or substantially equivalent right of access to a public hearing as a non-disabled person."

The Broadmoor inmate, who is judged to be capable of making his own decisions, gave evidence through a videolink, explaining that he wanted to have an open hearing so that members of the public "could be aware of what he sees as failings in the system, especially in relation to his diagnosis".

Mental health campaigners have hailed the decision as a landmark ruling. "This is an enormously important case," Lycette Nelson, from the Mental Disability Advocacy Centre, said. "It reinforces the idea that a person with a mental illness should be extended the same right to open justice as any other person should they want it."

Dr Andrew McCulloch, chief executive of the Mental Health Foundation, said: "If an individual is deemed through proper assessment to have sufficient mental capacity to decide whether their tribunal is heard in public, it is of course perfectly correct that their decision be respected."

Broadmoor Hospital told the tribunal that it feared approving a public hearing would lead to a flood of similar petitions.

The inmate said in a statement issued through his solicitors: "I have been compulsorily detained for over two decades to receive psychiatric treatment for a mental illness that for many years I disputed and which, in 2008, was deleted."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments