A Pissarro painting, the struggle to pay for care and the public's right to know

Following a campaign to report on the Court of Protection, a son's plea for publicity has illustrated the very difficult issues it is forced to confront

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It began with a call about a Pissarro painting. Earlier this year, a man whose elderly father had been taken into care contacted The Independent and said his local authority wanted to sell off a series of family heirlooms. Among the items the council was hoping to auction in order to pay for the elderly man's care bills was a 1906 landscape by the Franco-British artist Lucien Pissarro.

The man's son insisted his local authority was being mendacious, refusing to return his father to his home and choosing to auction items that held deeply sentimental value to the family.But the full story is significantly more complex. After The Independent successfully led a consortium of news organisations to seek access to the case in the Court of Protection, it can now be revealed for the first time.

Far from being mendacious, the court was told how the local authority had bent over backwards to accommodate the son's wishes, despite the fact that he had spent more than £70,000 of his father's assets without permission and had been allowed to live in his house rent-free. The judge, meanwhile, spared the man a referral for prosecution and a potentially lengthy jail sentence after he repeatedly committed contempt of court by illegally posting details about the case on Facebook, with his local newspaper and on the walls of his local fish-and-chip shop.

The case is important because it sheds light on how councils must find ways to pay for elderly patients who may need years of round-the-clock supervision. It also reinforces the importance of media being able anonymously to report complicated cases in private court hearings so that both sides of a story can be told accurately and the public informed about how such courts work.

With a population of increasing longevity, requests by local authorities to sell someone's assets are becoming increasingly common. Once someone becomes incapacitated and needs expensive assistance, possessions can be sold off to pay for that care. But the sale of such items can often prove deeply traumatic for a patient's family.

The problem with accusations of wrongdoing from relatives of patients is that they are difficult to assess because care proceedings for those who have lost the capacity to make vital decisions about their lives are dealt with by the Court of Protection.

Most proceedings within the important but little-known Court of Protection are held in private and the media have to apply to report on individual cases – a complex and expensive system that The Independent has tested ever since it first won the right to report Court of Protection cases three years ago.

The man – who is referred to as "RBS" in court documents to protect both him and his father – was dramatically saved from a spell behind bars because of his own fluctuating mental health. During two hearings in June and November, the court heard how the man "had a long history of involvement with mental-health services" and could be "irrational and unpredictable". As the case progressed through the court, he "bombarded" court officials, the media and social websites with updates and details of the case – information which ought by law to have been kept private, in order to protect the privacy of his father. He also issued a habeas corpus writ and applied to the European Court of Human Rights claiming that his father was imprisoned.

At a hearing to decide whether the man had the capacity to litigate in proceedings, the man insisted he was in full control of his faculties, leading District Judge Anselm Eldergill to warn that he could face prison if that was the case.

Three witnesses – neighbours and friends of the man – testified that his actions were motivated by a desire to have his father return home from care and a belief that the care home was not the best place for him. The judge described the witnesses as "kind-hearted, compassionate, truthful, intelligent and loyal to their friend" but added that they were largely unaware of how the man had behaved towards the court in recent months and that he had originally consented to his father's placement in the care home.

Care officials, meanwhile, insist that the elderly man's interests are best catered for in a care home.

In the end, the judge, an expert in mental-health law, made an interim order stating that there was enough evidence to believe the man lacked the capacity to litigate, pending further examination by medical professionals. But he added that he would do everything he could to avoid sending the man to jail.

The judge also praised the local authority for the way it had handled matters. "[RBS's] highly adversarial approach to litigation suggests he is unable to understand the deputy has been caring and generous towards him," he said. "He has been permitted to reside rent-free at his father's cottage, there have been no applications to commit him, despite fairly vicious public attacks on council staff, and his unauthorised dealings with his father's assets have been discounted. This is not a case of a bullying local authority abusing its powers over a vulnerable adult and their family; quite the opposite."

It will be down to the court to decide at a later hearing whether the sale of the Pissarro paintings should indeed go ahead. The court heard how the local authority was facing a shortfall of £14,400 a year to cover care costs once the elderly father's income was taken into account. He also has liabilities of more than £100,000 which need to be paid off. Both his son and daughter owe him money and the council could look into renting the cottage where his son lives. The Pissarro painting, the court heard, is expected to fetch between £20,000 and £30,000 at auction.

But in a stark warning against continued litigation, the judge cautioned that he was keen to avoid a "Jarndyce vs Jarndyce" situation – a reference to a fictional court case in the Charles Dickens novel Bleak House in which a legal battle over a handsome inheritance drags on for so long that the money is depleted.

"Given that the trigger has been whether the heirlooms have to be sold," he said, "a 'Jarndyce vs Jarndyce' situation cannot be allowed to develop which means [the heirlooms] have to be sold to pay the legal costs incurred deciding whether they should be sold."

The next hearing is due to take place early next year.

Picture this: Pissarro's life

The eldest son of the famous Impressionist painter Camille, Lucien Pissarro is a lesser-known artist but one who has an indelible connection to Britain. Born in 1863, he grew up in France surrounded by his father's peers such as fellow Impressionist founders Cézanne, Manet and Monet.

His father had a brief sojourn in Britain to escape the Franco-Prussian war and from then on would often wear tweed and insist on marmalade for breakfast.

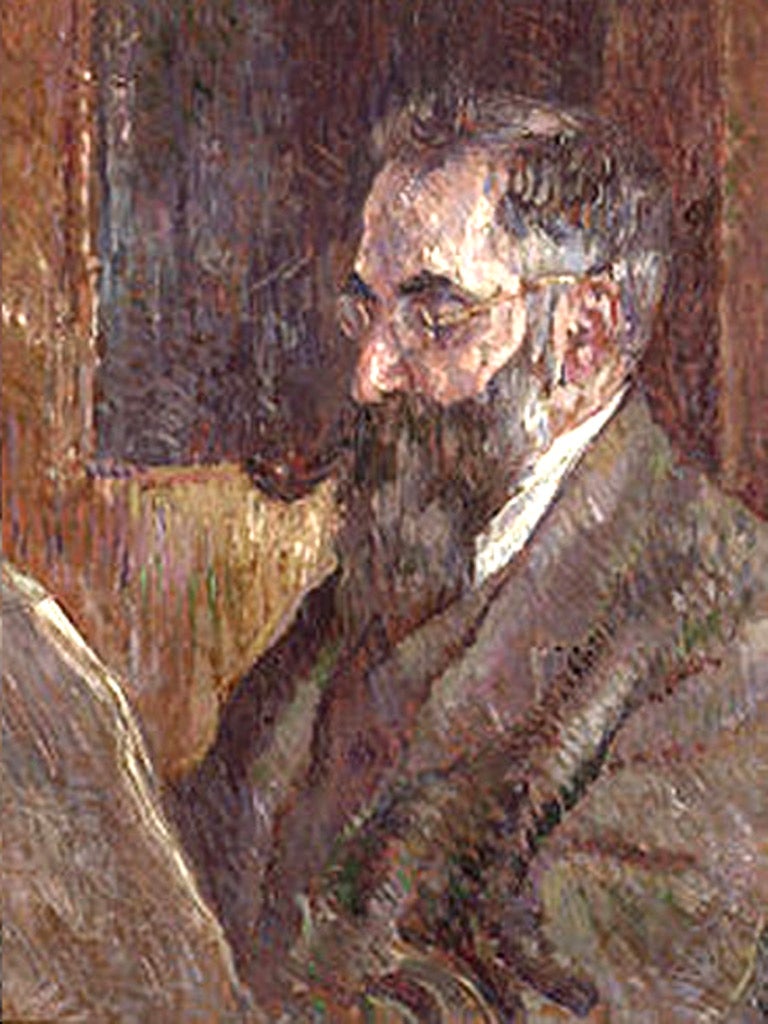

Skilled as a painter in oils and watercolours as well as wood engraving and lithography, Lucien, pictured left in a self-portrait, felt like he lived in the shadow of his father and in 1883 he made his first trip to Britain, partially to put some distance between his own work and Camille's Impressionism. He eventually settled here permanently after marrying an English Jewish woman called Esther Bensusan.

Together they founded an illustrated-book company, while Lucien continued to paint haunting landscapes that fused both French Impressionism and the more traditional schools of English art that were current at the time.

He became a naturalised British citizen in 1916 and spent much of his time recording landscapes in Dorset, Devon, Essex, Surrey and Sussex.

Lucien and Esther's only child, Orovida, also became a prominent British artist in her own right.

Jerome Taylor

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments