The North Wales child abuse scandal: A damaged generation waits for justice 30 years on

Many of the abused care home residents were to die in horrifying circumstances – while the survivors live in fear. Roger Dobson, who has covered the story for two decades, reports

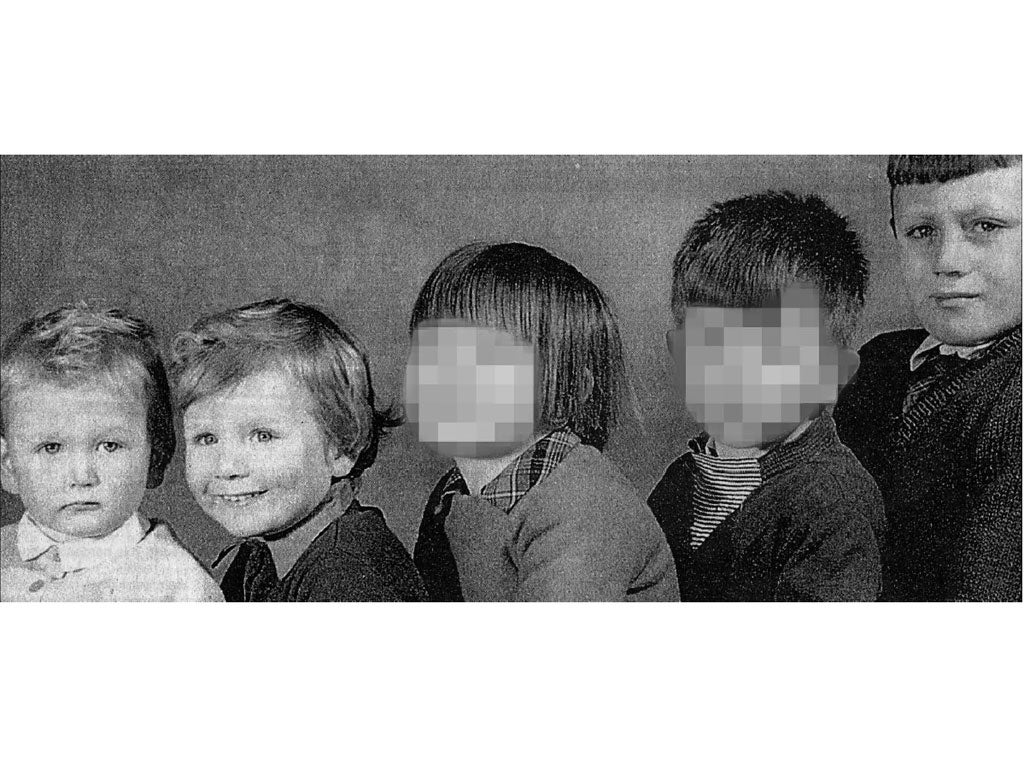

It should be a happy family portrait. Like millions displayed on family mantelpieces all over the country, it shows young siblings, hair slicked down, normally wayward clothes pulled straight. Here the resemblance ends; for the children in this picture are – for the most part – victims of unspeakable horror.

The four brothers were subjected to physical beatings, three of them were passed around and endured terrifying abuse by paedophiles. Two are dead, one in horrifying and unexplained circumstances. The remaining two live in terror at the margins of society, racked by the fear that the men who spent years hurting them will return.

While the country obsesses over the fate of George Entwistle, Newsnight, and allegations of paedophile rings in high places, the lives of scores of victims of abuse in North Wales are once again touched by the fear and shame with which their experiences in council care left them. For Adrian and Lee Johns, pictured here, it is already too late. Adrian was unlawfully killed in an arson attack in the Brighton area in 1992. He had been with other young people who had been abused at the Bryn Estyn children's home in North Wales when they were killed. His brother, Lee, died three years later of a drugs overdose.

Their brothers, Jay and Chris, have dropped off the radar. More than a decade ago, they were in hiding, fearing that their brothers had been the victims of foul play and that they were next.

The grim fate of the Johns family is not exceptional. Countless other former residents of North Wales children's homes live similar lives. Most have long since given up hope of justice; most are deeply damaged by what they have endured: beatings, bullying, sexual abuse and rape. Those who survived, that is. Adrian and Lee are just two of more than a dozen to have died prematurely – many, it is believed, as a direct consequence of their experiences in care. Men such as Mark Humphries who hanged himself, aged 31, after reporting sexual abuse. Simon Birley and Peter Wynn, both 27, also committed suicide after suffering similar abuse, and Robert Arthur Smith overdosed on painkillers, aged 16.

They are just a handful of victims to suffer abuse that spanned two local authorities, more than a dozen residential children's care homes, involving hundreds of children and scores of staff, along with an unknown number of outside abusers. The abuse spawned a handful of police investigations, and at least one review of those; two inquiries, one led by a High Court judge; a clutch of court cases; and hundreds of compensation cases.

Of the hundreds of children who passed through residential care in the Seventies and Eighties, more than 150 came forward to give evidence to an official inquiry carried out by Sir Ronald Waterhouse in 1996 after concern about a care homes cover-up prompted the Government to act. The witnesses' pain-filled testimonies frequently silenced the bustling inquiry. The inquiry's senior counsel, Gerard Elias QC, while pointing out that it took great bravery to relive those painful events, said the volume of statements was impressive: "If accepted [by the tribunal] ... they will compel the conclusion that children in care in Clwyd and Gwynedd were abused physically and sexually on a scale which bordered on wholesale exploitation."

Most of the children were, in many ways, victims even before their brush with the child care system in North Wales. They came from broken homes, or had parents who could not cope. Some had behavioural problems and some had already been abused. Most were easy pickings. Many of the staff who abused them didn't even have to fill out a job application. Inevitably, paedophiles passed the word to the like-minded that the residential care homes of Clwyd and Gwynedd were soft targets. The victims who remained silent enjoyed privileges such as extra TV, sweets or money and outings, while the ones who complained were punished for telling lies.

Many of the indicators of abuse had been there to be noticed for some time, and it is to many people's shame that allegations were not taken seriously before: there had been children running away from home; there were complaints about staff and their lack of care; there was the lack of regulation and the entry of highly unsuitable people joining the staff. In some cases, the children's homes were run at arm's length from the local authority, while in others they were run as private operations. They were out of sight, and out of control. The children were an invisible underclass.

Some were able to articulate what many of them felt – that their failure to speak out at the time made them accomplices. Their complaints aired at the inquiry came at a time when many had settled down in life. But they remained deeply troubled – and their sense of injustice at what had happened to them grew.

In 1999, the fruit of the Waterhouse inquiry, the report Lost in Care, criticised nearly 200 people and made 72 recommendations for changes, sparking a massive overhaul of the way in which children in care are dealt with by local councils, social services and the police.

Among the changes was the creation of the post of Children's Commissioner for Wales. Yesterday, Keith Towler, the current commissioner, said he had received up to 50 calls involving fresh allegations of abuse in care homes. He said people were approaching him and his staff, in preference to going to the police. "They're saying, 'I've waited 30 years to have this opportunity.' This is not an archaeological dig. We're talking to people for whom this is terribly alive."