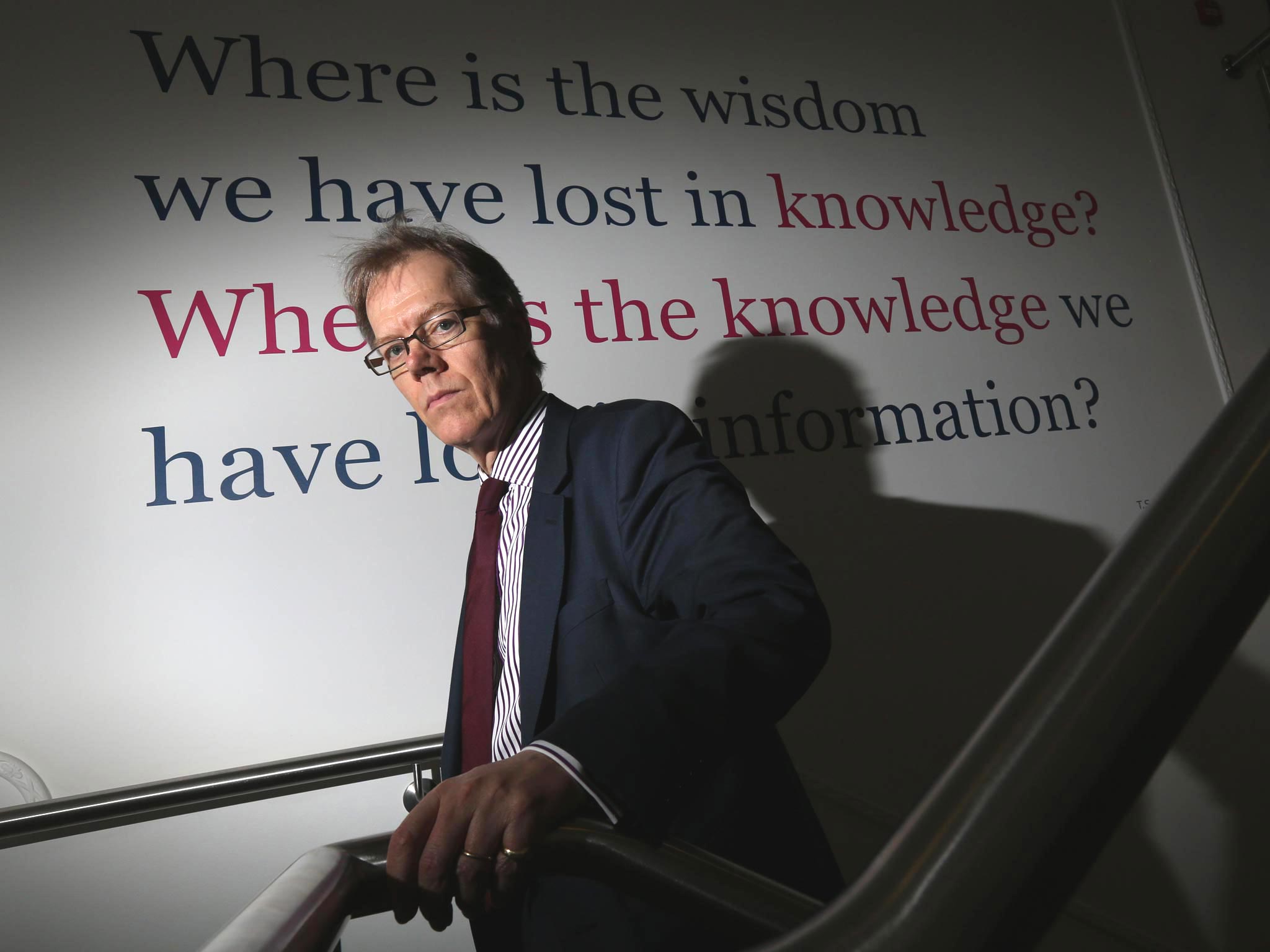

Privacy guardian Christopher Graham finds himself in the public eye

Christopher Graham’s role as information commissioner has seen him achieve a level of recognition he didn’t expect when he took the job in 2009 – but he’s signed up for another two years, says Ian Burrell

For a guardian of the nation’s privacy, Christopher Graham is having to grow used to incursions into his own personal space as the public confronts him on buses and in hotel lobbies with concerns over the safety of their intimate details.

The information commissioner didn’t expect this level of recognition when he took the job in 2009 but his tenure in what had previously been a relatively low-key post has coincided with a data revolution.

Mr Graham, 63, finds himself interviewed on television about lost medical records, and summoned to the Leveson Inquiry to answer questions about private investigators “blagging” secrets from banks and phone companies. His office has been front-page news after The Independent’s revelations that blue-chip companies are accused of illegally obtaining the public’s private information.

“It’s top of people’s agenda – both citizens and politicians and businesses. Everyone wants to know what the information commissioner is going to do,” he says. Clearly he has enjoyed the experience, because last week it was quietly confirmed that he has signed up for a further two years in the role.

But that doesn’t mean he thinks he has the tools to do what is an increasingly demanding job. He has “pretty limited powers” and is frustrated that some of his office’s recent prosecutions have been thrown out.

“I had one of our fines struck down the other day because I couldn’t prove that dumping all the pensions records in the recycling area of the local supermarket was going to cause serious damage or distress,” he complains, of an attempted prosecution of Scottish Borders council. “I couldn’t prove that someone of malicious intent had picked up all this personal information and was going to be doing people down.”

The information tribunal also rejected his office’s attempts to prosecute Tetrus Telecoms for sending thousands of spam text messages because the judge didn’t accept that substantial damage and distress had been caused.

“We could show there was nuisance – that isn’t enough apparently,” says the commissioner. “We have just got to lower that hurdle because I think if you ask most people they would say silent calls and unsolicited spam texts are one of the great curses of the age – and if the Information Commissioner can’t protect you it’s a poor lookout.”

Under data-protection laws, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) can only bring monetary penalties. Even the criminal offence of unauthorised disclosure or obtaining of personal information (Section 55 of the Data Protection Act) carries only a fine and is often dealt with by a magistrate.

“The track record in the magistrates court is pretty pathetic,” says Mr Graham. If people don’t think this sort of thing matters and if you get to the magistrates court you will be fined about £120, not surprisingly the public doesn’t have great confidence that their personal information will stay secure.”

This lack of confidence, he says, has huge implications for the Government’s plans to improve public-sector efficiency by moving services online.

“If you don’t have confidence in the way data controllers will handle all the information they are bound to hold on us these days because we are doing everything online then – surprise, surprise – you don’t have the public confidence for the big data-sharing initiatives that the Government wants to see in the public service.”

More serious cases of information theft – such as the recent prosecution of private eyes ICU Investigations, who received fines of up to £7,000 – are dealt with in crown courts, which can impose unlimited monetary penalties. But jail sentences – which information commissioners have called for since 2006 – are not in the armoury.

“It feels like it’s groundhog day,” says Mr Graham.

A provision for custodial sentences is included in the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act but has not been commenced into legislation because, as the commissioner says, it was “caught in the reeds of the Leveson Inquiry”.

Some in Fleet Street appear hostile to the commissioner having more powers, but Mr Graham accuses them of flawed thinking.

“You can’t have it both ways,” he says. “You can’t say we don’t do this sort of thing and by the way it would be a terrible attack on investigative journalism to commence this legislation.”

The ICO, which is based in Wilmslow, Cheshire, has not been immune to public-sector cuts and has seen its budget reduced from £5 million, when Mr Graham arrived, to £3.75 million next year. He is exasperated by “rickety” funding mechanisms which mean he must keep separate spending pots for his two areas of responsibility: promoting freedom of information and maintaining data privacy. Both subjects are attracting growing numbers of complaints.

Mr Graham, who had a long career at the BBC as a radio and television journalist before becoming director general of the Advertising Standards Authority in 2000, would like a new data tax to create a single, ICO fund.

“I would have thought an information rights levy, paid for by public authorities and data controllers [is needed]. We would be fully accountable to Parliament for our spending.”

Following Edward Snowden’s revelations of GCHQ’s mass collection of personal data (including phone calls, emails and use of social media), Mr Graham has written to Sir Malcolm Rifkind, chair of Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee.

“We have said there has got to be a democratic and accountable oversight regime for the security services’ access to data; we have got to understand how it works,” he says. “It’s no longer convincing to have a senior Privy Councillor saying ‘OK chaps, it’s fine’.”

He says the public is more exercised by the NHS England care.data programme of a giant store of individual medical records than it is worried about Snowden.

“People have been challenging me on the bus about care.data. That’s the talking point but Snowden hasn’t been, which is kind of a surprise.”

He is critical of the NHS’s efforts to explain the care.data system, saying the ICO had advised individual letters to all patients.

“They said ‘No, we’re going to do a leaflet.’ I never received my leaflet,” he says.

He has the right to compulsory audit of local government organisations which he criticises as “hopeless” in their handling of personal data.

“It just happens far too often, that a social worker loses a memory stick, an unencrypted laptop is taken for home working and gets nicked after being left in the pub,” he says.