Parsons Green bomber's Isis inspiration was missed by police investigation

Exclusive: Independent investigation proves Ahmed Hassan listened to Isis propaganda after prosecutors claim there is 'nothing to suggest' inspiration

Police botched their investigation into Isis propaganda that inspired the Parsons Green attacker and failed to link him to the terrorist group, The Independent can reveal.

Ahmed Hassan, an 18-year-old Iraqi asylum seeker, is facing life imprisonment for attempting to bomb a District Line train in London.

Isis claimed responsibility for the blast within hours but the Old Bailey was not presented with any proof that Hassan communicated with militants or supported their cause.

“There is nothing to suggest he was inspired by Daesh [Isis],” the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) told The Independent.

Our investigations show that police found evidence of Hassan’s affiliation with the terrorist group, but misinterpreted the material and sent flawed information to prosecutors.

The blunder could affect the jail term handed to the bomber on Friday and The Independent has submitted urgent evidence to the Old Bailey ahead of the hearing.

Justice Haddon-Cave will have the power to increase Hassan's jail term under terrorism laws, and any link to Isis could mean harsher punishment.

The teenager destroyed his mobile phone and wiped a laptop given to him for college work, hampering the investigation into what drove him to launch the attack on 15 September.

But police searching his foster home in Surrey found a memory stick containing Arabic nasheeds – Islamic songs.

Officers translated the audio files and provided English transcripts showing how they encouraged violence in support of the “state of Islam” against the “coalition of falsehood”, but failed to identify the songs as Isis propaganda.

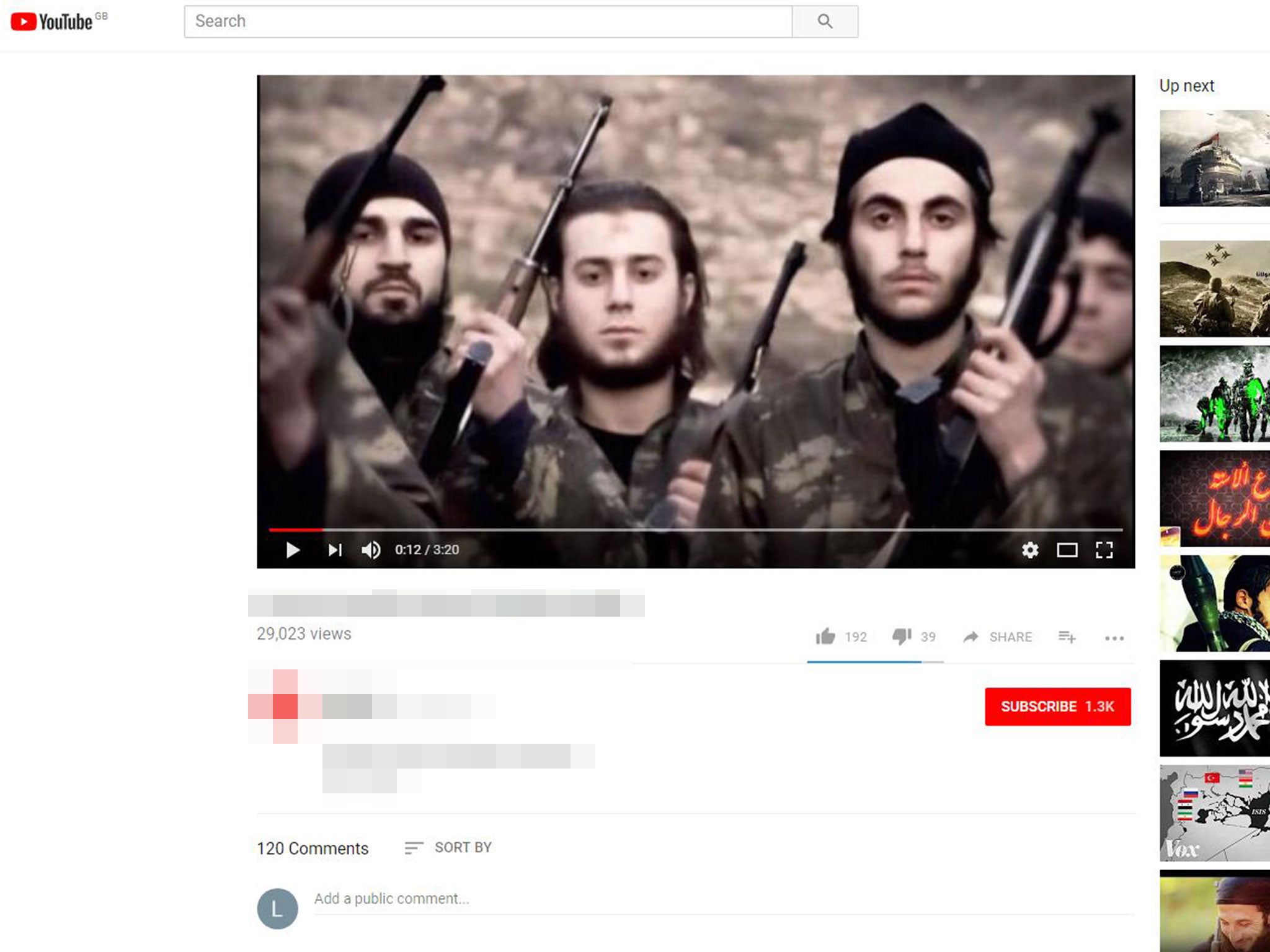

Two nasheeds The Independent were given details of were released by the terrorist group’s dedicated propaganda wing for songs.

One is among the group’s most well-known nasheeds and remains available on YouTube and other websites at the time of writing, calling for global terror attacks.

It may be the song Hassan was seen listening to by a Barnardo’s charity worker, which was supporting him as a child asylum seeker at the time.

The member of staff, who spoke Arabic, said the teenager was listening to a song on his phone including matching lyrics threatening “slaughter”.

The second nasheed examined by The Independent was also released by one of Isis’ official propaganda wings and calls for disbelievers to be “destroyed” in graphic terms.

Charlie Winter, a senior research fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) at King's College London, said he was “surprised and a little troubled” that specialist counter-terror police failed to identify the material.

“It seems they’ve dropped the ball on these nasheeds and this is problematic because it’s symptomatic of a broader unawareness of what nasheeds are, what they do and the fact they are produced in-house by Isis,” he added.

“There’s little question that it’s Isis propaganda, and it’s the stuff you wouldn’t really know about unless you’re thinking deeply about the group and its aims.”

Mr Winter said the two songs in question were specifically released to incite violence and one was featured in a mass beheading video.

“Nasheeds are an important part of the fabric of Isis’ political culture,” he explained. “They are enormously symbolic and among the most recognisable outputs of its propaganda over the past few years.”

Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, a research fellow at the Middle East Forum, told The Independent that translations presented to court were also inaccurate.

“It’s pretty hard to claim Hassan was not inspired by Isis if he was listening to these nasheeds,” he added.

The songs are not the only evidence of Hassan’s support for Isis – a teacher saw him watching a video featuring the black Isis flag and another boy taken in by his foster parents described him as “brainwashed” and “mad”.

He was reported to the Government’s Prevent counter-extremism programme on at least two occasions and authorities are investigating how he was still able to launch the attack.

Police said the “devious” teenager appeared to engage with the project while secretly plotting the terror attack.

Hassan had been flagged as a potential risk just days after being interviewed by social services in January 2016, three months after he arrived in Britain in the back of a lorry from Calais.

Then 16, he told immigration officials he was being forced to become an Isis child soldier in Iraq and had been “trained to kill” by the terrorist group.

But while giving evidence to the Old Bailey, Hassan said he actually had had no contact with Isis and lied because he wanted to claim asylum.

Much of the teenager’s life remains a mystery – to police as well as his classmates, teachers and foster parents.

The couple described Hassan as agitated in the weeks leading up to the bombing, taking phone calls out of earshot in the garden and late at night that remain unexplained.

Metropolitan Police Assistant Commissioner Neil Basu, the new head of UK counter-terrorism policing, admitted his officers were “not perfect”.

He told The Independent he was not aware of errors in the Parsons Green case, saying: “If we’ve got a gap in capability or if we’ve misread something and those nasheeds are still out there and available to others then we definitely want to fill that gap.”

Mr Basu said officers were working to crack down on extremist material online, with some lone actors being influenced by a variety of groups.

He hailed success removing terrorist posts and catching people downloading and viewing propaganda, but warned that the volume of evidence on seized phones and electrical devices was a challenge.

“We’ve got a serious issue with the volume of digital media, what we’re able to analyse and what we’re able to put before the prosecution,” he added.

“It has increased many, many-fold in just a couple of short years, so I’m concerned that we haven’t got enough resource to be able to look at the vast range of material quickly enough to get everything into a case.”

The Parsons Green case followed serious errors in material published by the CPS on other terror cases.

In December, it wrongly described an al-Qaeda propaganda video as Isis material following the conviction of terror plotter Mohammed Awan. A press release was updated following a correction from The Independent.

In May last year, a draft prosecution opening incorrectly named an American extremist who was killed in a 2011 drone strike as a spokesman for Isis, which was not formed until three years after his death.

The CPS declined to comment.