Mohammed Abdallah: How an unemployed Manchester cannabis dealer became an Isis sniper in Syria

Abdallah was part of the same jihadi network that spawned Manchester bomber Salman Abedi

Mohammed Abdallah is an unemployed former drug dealer who left school with no qualifications and has an IQ of just 68.

His journey from cannabis-smoking dropout to Isis sniper mirrors the transformation of many young men in his home city of Manchester and across the UK.

The 26-year-old has been jailed for 10 years for joining Isis in Syria, possessing an assault rifle and receiving £2,000 in terrorist funding.

His brother, notorious Isis recruiter Abdalraouf Abdallah, helped him travel to the war zone alongside other Manchester jihadis, including Stephen Gray, Raymond Matimba and Nezar Khalifa.

It is the same network of terrorists that spawned Salman Abedi, who killed 22 people by blowing himself up at Manchester Arena in May.

It remains unclear whether Abdallah and Abedi knew each other well, but the pair lived in the same area of Manchester, attended the same school, shared friends and many other characteristics including drug use and a record of petty crime.

Experts have been warning of a growing “crime-terror nexus” seeing criminals drawn towards Isis by its promise of purpose, action and adventure.

Isis’ ideology puts less emphasis on Islamic piety and more on absolute obedience to its own interpretation, generating a shift from radical Islamists to what experts call “Islamised radicals” already disposed to violence and criminality.

Some of Europe’s deadliest terrorists have taken the same path, including Westminster attacker Khalid Masood and the Isis “super cell” behind the Paris and Brussels attacks.

A United Nations report found that foreign fighters mainly come from disadvantaged backgrounds, have low levels of education and “lack any basic understanding of the true meaning of jihad or even the Islamic faith”.

Like Abdallah, a typical fighter was found to be young, male, unemployed, living in an inner-city area and “feeling their life lacked meaning”.

Abdallah was only inside the so-called Islamic State for a matter of weeks, but a judge at the Old Bailey found he was a danger to the British public and those abroad.

Mrs Justice McGowan threw out his claim not to have heard of Isis before arriving in Syria in July 2014, telling the court Abdallah’s “intention was clear” from uncovered online messages and his previous fighting experience in Libya.

“You bragged about obtaining weapons,” she told the defendant. “You were totally committed to joining a proscribed organisation and did join Islamic State.”

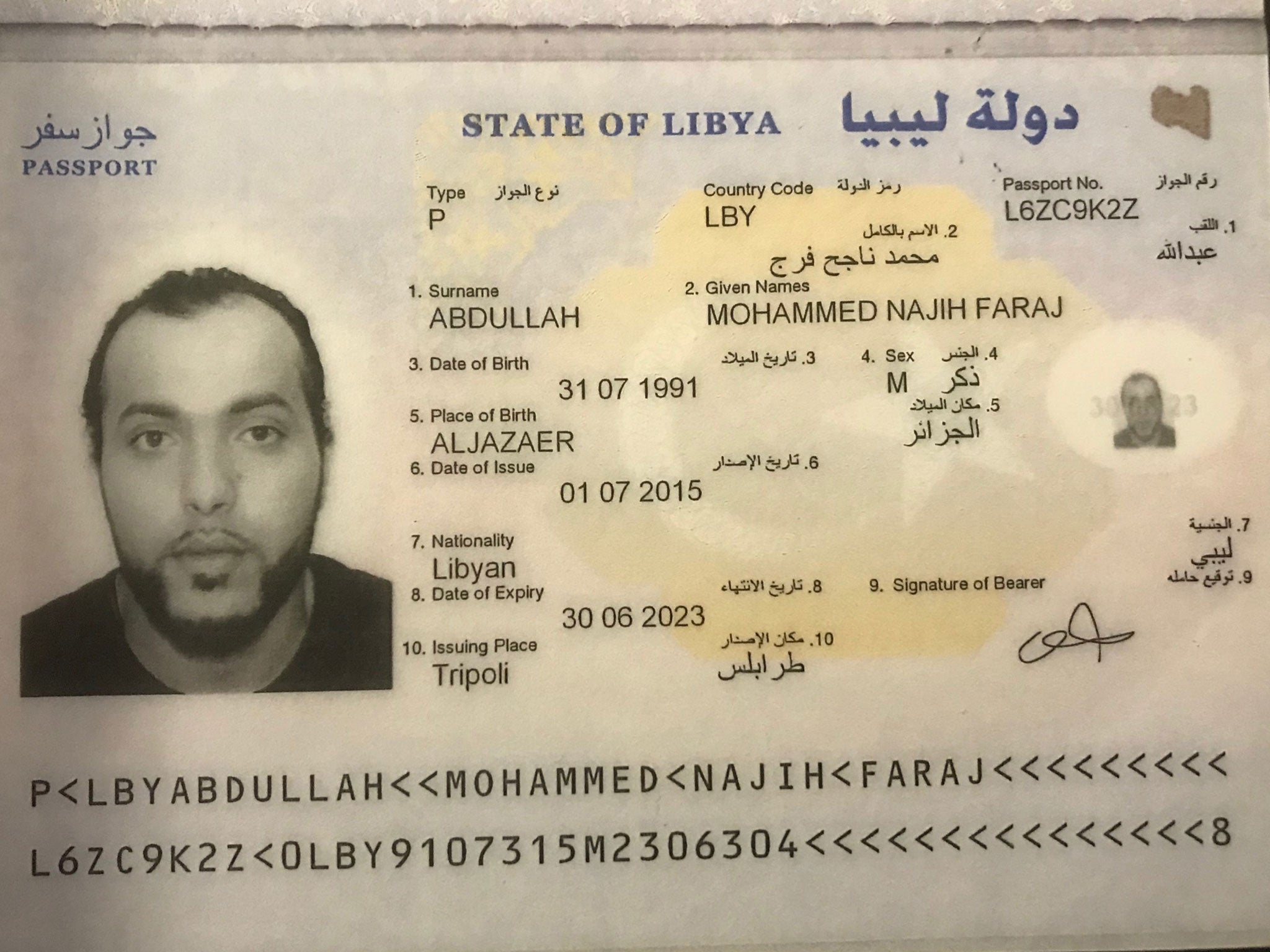

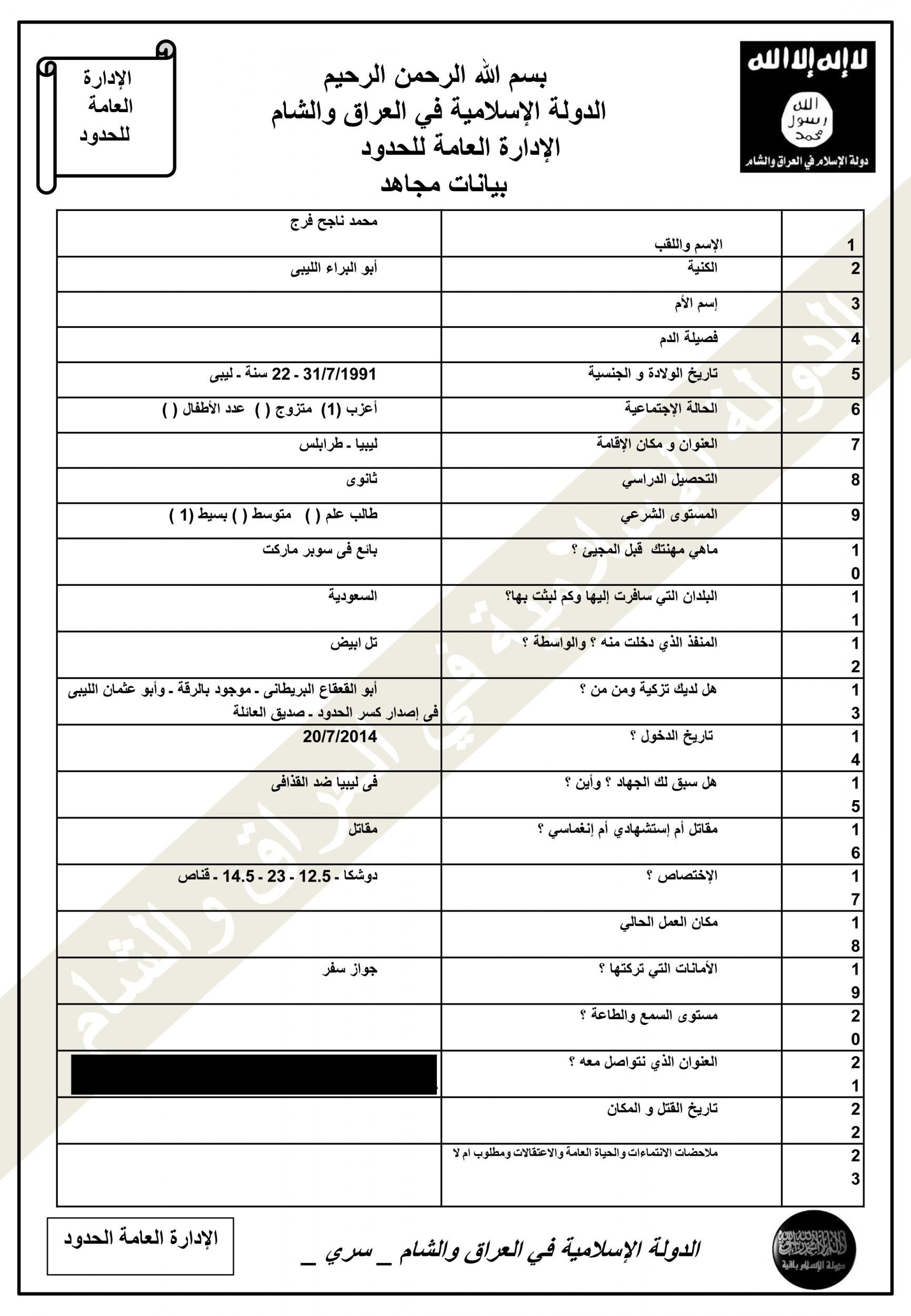

Abdallah’s conviction was sealed by a leaked Isis document listing him as a fighter specialised in sniping and using a Russian-made machine gun, although with a “basic” knowledge of Islam.

The form – which Abdallah claimed was filled out without his knowledge – described him as a “beginner” in Islamic law and former supermarket vendor, although the unemployed man claimed he actually made money by stealing and selling cannabis in Manchester.

It also described his previous experience fighting against Muammar Gaddafi’s forces in Libya, where he joined an Islamist militia years before alongside his brother, who was left wheelchair-bound after being shot.

Justice McGowan said Abdallah “remained undeterred by seeing death and injury inflicted in those battles”, after being trained to use a semi-automatic weapon in experience that was “of significant value” to Isis.

“The evidence of your mindset is to be found in your actions,” the judge added. “Your commitment to violence abroad is clear and you have not shown any sign of having changed your views or attitude.”

The judge said it was “not possible to identify all movements or actions” during his month inside the caliphate, after which he left and travelled inside Syria before returning to Libya and joining a government militia.

Following his brother’s conviction, Abdallah voluntarily returned to the UK after his family contacted authorities and was arrested upon arrival at Heathrow Airport.

Giving evidence, Abdallah denied swearing allegiance to Isis and claimed he only went to Syria to help deliver money to the poor.

“They did send me to prison,” he told the court. “I was threatened with being beheaded. I was shot at. I was hit. I had bruises and a black eye.”

After being released from prison, Abdallah will be on licence for five years, as well as being required to notify security services of his whereabouts and other details for 30 years.

His only previous brush with the law was a conviction in 2013 for assaulting a police officer while under the influence for drink or drugs.

Neither were unusual in Abdallah’s previous life, which saw him struggle at school and lead a rootless existence dealing and smoking cannabis before finding bloody purpose in the Libyan civil war.

He was born to Libyan parents but arrived in Britain at the age of three after his parents fled the oppressive Gaddafi regime, living in Moss Side and attending the Burnage Academy for Boys – the same school as Abedi.

Abdallah’s trial was delayed because of his links with the bomber, who also attended the Didsbury Mosque alongside the brothers and Hostey.

Abedi is additionally reported to have visited Abdalraouf in HMP Altcourse, Liverpool, in the months leading up to his attack.

Like the future bomber and many members of the Libyan diaspora in Manchester, Abdallah and his brother travelled to fight Gaddafi’s forces in the 2011 uprising and joined the Islamist “Tripoli Brigade”.

Abdalrouf was shot and partially paralysed in battle, returning home to Britain and becoming a prolific recruiter and facilitator for Isis fighters travelling to Syria.

Abdallah later travelled via the country to Syria in July 2014, where he planned to meet Gray and Matimba.

Gray was turned away in Turkey and has since been jailed, but Matimba eventually caught up with the others and appeared in footage with the Isis executioner known as Jihadi John.

Messages showed Abdallah showed support for both Isis and its predecessor al-Qaeda faction Jabhat al-Nusra before arriving in Syria, the Old Bailey heard, receiving guns and training with them before receiving £2,000 from his brother.

His details were entered on the Isis form around 20 July 2014, formally marking his migration into Isis territories.

Abdallah’s references were given as Hostey, who was already living in Raqqa and was killed in a drone strike, as well as a Libyan Isis member who narrated a propaganda video described as a “family friend”.

The same area of Manchester was where the Abdallah and Abedi brothers lived was home to more than a dozen convicted, killed or active terrorists, drawing scrutiny to southern districts and the Libyan diaspora in particular.

Detective Chief Superintendent Dominic Scally, head of the North West Counter Terrorism Unit, insisted the number was small compared to the city’s population.

“That’s not indicative of the communities we work with on a daily basis,” he told The Independent.

“This is a small number of people who made personal decisions based on their life experiences and I don’t think we can generalise and say that’s an indication of how a community is, because that’s not our experience in Manchester.”

Mr Scally said the Manchester terror network grew as a consequence of members’ relationships and regular contact, rather than a particular community or location.

He added: “It’s difficult for us to know why people made those decisions, how they became radicalised.

“They’ve all got their own life experiences and relationships and those will undoubtedly have influenced their decisions.”

The senior officer said that although Abdallah showed no specific threat to the UK after his return, anyone with terrorist sympathies and fighting experience was a security concern.

Around half of the 850 people who travelled to the UK to Isis territories in Syria have already returned, but prosecution is only possible when authorities can prove they committed a criminal offence abroad.

All known foreign fighters are monitored before they return to Britain and thoroughly investigated upon their return, Mr Scally said.

“That may take many different forms and in this case it was arrest, interviews and a criminal justice process,” he added.

“We are committed to doing that thoroughly for everyone who returns from a conflict zone until we understand what, if any, threat they pose to the UK.”