Curse of Brink's Mat: Death of John 'Goldfinger' Palmer the latest killing related to 1983 heist

Palmer's relationship to the Heathrow robbery dramatically changed his life

“He who has the gold, makes the rules,” was a favourite saying of John “Goldfinger” Palmer. He who had the gold was also fond of breaking them, he might easily have added.

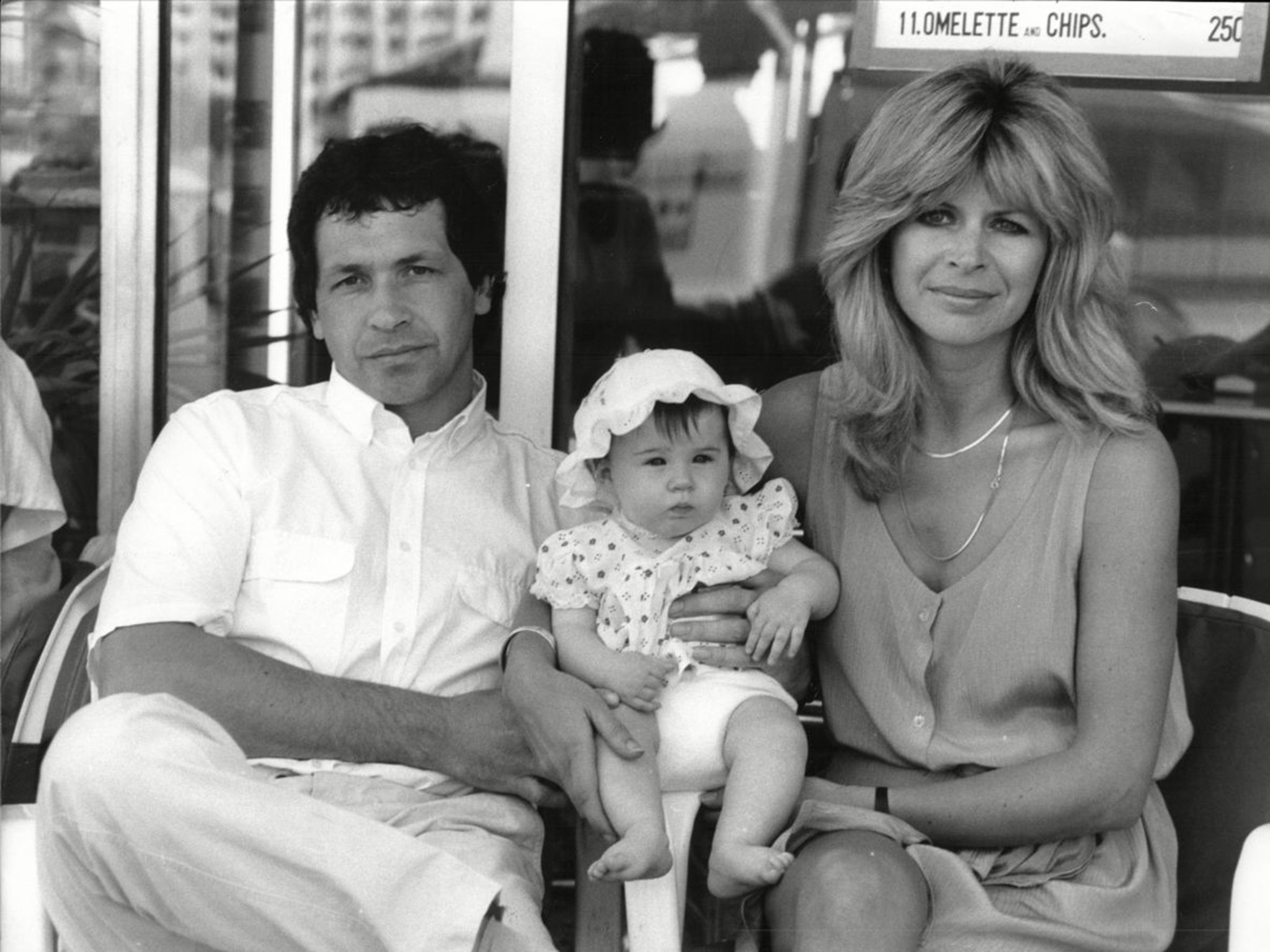

His fondness for the motto stems not just from the fact the rare metal bequeathed him his nickname but more from the fact that his relationship to the three tons of gold stolen in the 1983 Brink’s-Mat robbery at Heathrow Airport dramatically changed his life.

Palmer’s involvement stemmed from his ability to smelt and his intimate knowledge of the gold and jewellery business, which helped the thieves reap the rewards from the haul.

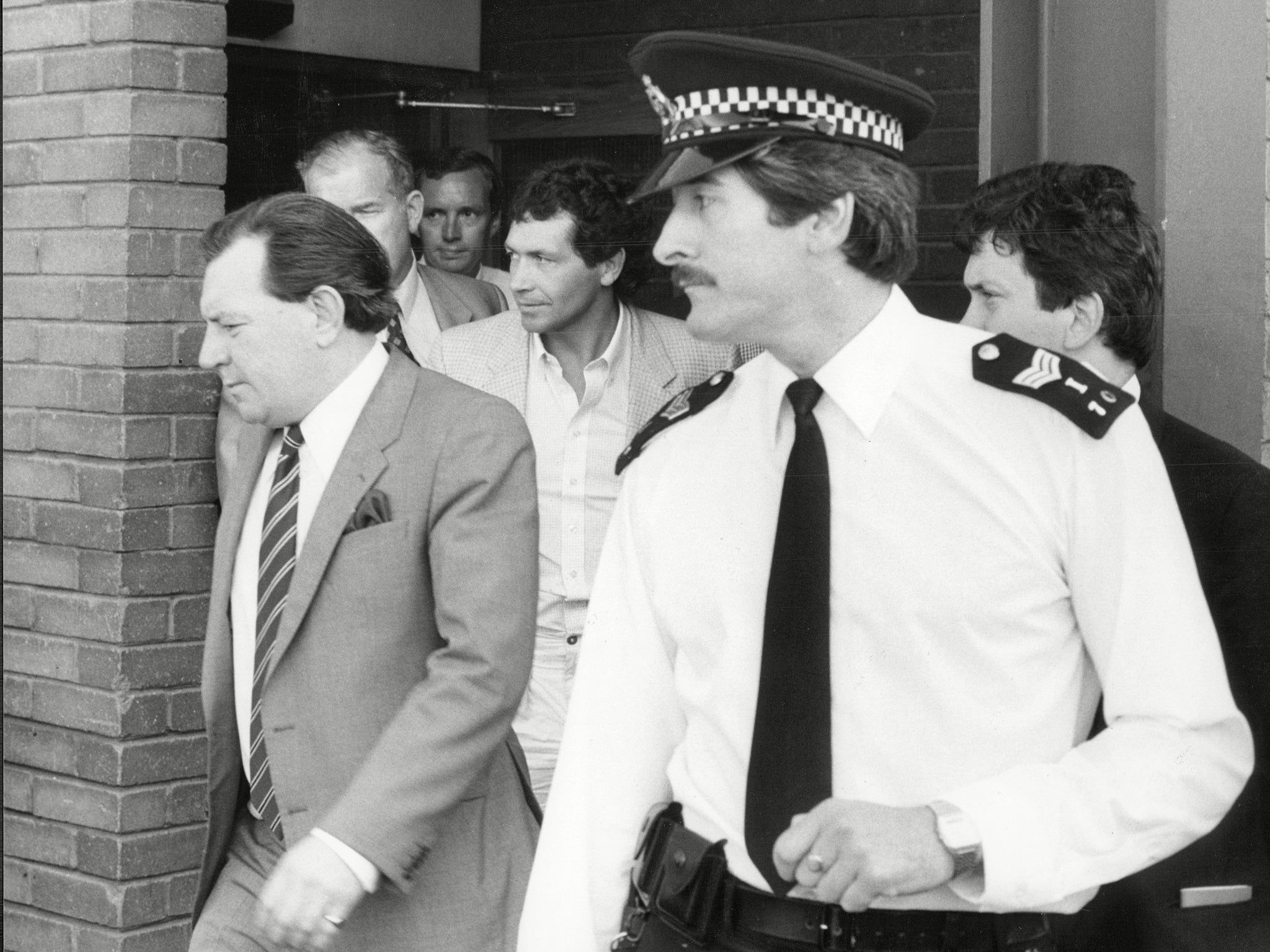

His acquittal of laundering the gold at the Old Bailey in 1987 saw him quit the UK and move to Tenerife, where his timeshare business was rapidly developing into a multi-million-pound industry.

Palmer would later insist the success of the business was already under way before the robbery. The sale of his chain of West Country jewellery stores after the trial fuelled its expansion. But detectives believe Brink’s-Mat proceeds also fuelled it.

Palmer rapidly became a magnet for those involved in the burgeoning drugs trade. Spain, with its historical and commercial links to South America, was soon a crucial link in the supply of cocaine to wealthy European markets.

Palmer was perfectly placed to help solve the traffickers’ laundering problems by using his “legitimate” businesses in Tenerife and elsewhere in Spain to wash criminal cash. He boasted to an undercover TV reporter he could launder £60m a year. He came to be at the nexus of organised crime that stretched from Colombia to Russia and from Britain to Morocco. His wealth spiralled, making even the £26m haul from Brink’s-Mat seem minor against the profits that could be reaped from drugs.

But as hard as Palmer tried to distance himself from the Brink’s-Mat gold after the trial, it kept coming back to haunt him. Much of the haul was never recovered and more than a decade later insurance investigators were still trying to follow its trail, which was an increasingly bloody one.

For while the presence of the gold transformed the lives of those touched by it, the absence of it dramatically altered others.

Palmer was found dead at his Essex home on 24 June. but it was only six days later, on Tuesday, that police discovered he had been shot in the chest, after first believing he had died of natural causes following heart surgery. Yesterday his family described the murder as a “great shock”, adding that speculation over the circumstances of his death has been “hurtful and bewildering”.

Palmer’s murder has breathed fresh life into stories that all those touched by the 1983 robbery have suffered from the Brink’s-Mat curse.

Among those said to have suffered were George Francis, who was repeatedly shot as he leant into his car through one of its door windows, outside the courier firm he ran in Bermondsey, south London, in May 2003.

Two men were convicted of the killing – said to have been ordered after Francis failed to repay an “old debt”. Allegations that surfaced before the trial suggested he was given £5m in Brink’s-Mat proceeds to help launder – but not all of it was repaid.

Two years earlier, and a short distance from where Francis was killed, cab firm owner Brian Perry was murdered in a similar fashion – shot three times in the back of the head as he walked from his car to his office.

Perry was sentenced to nine years in jail in 1992 for his part in melting down the bullion. Two men were tried for his murder in 2006 and acquitted after the case against them fell apart. His murder remains unsolved but rumours abound about the missing millions being at the root of it.

Great train robber Charlie Wilson was another victim. He was murdered in 1990 when he answered the door at his home in Marbella, Spain. The assassin, who escaped on a bicycle, also shot Wilson’s dog. The killing was seemingly ordered after £3m of the Brink’s-Mat haul was lost after he invested it.

London criminal Danny Roff was suspected of being a look-out in Wilson’s murder. He was shot dead in his car outside his home in south London seven years later.

Property investor Donald Urquhart was also involved in plans to launder the Brink’s-Mat proceeds. It proved a bad investment. He was shot dead in a central London street, in January 1993.

The motorcycle rider who shot him was paid £20,000, a court was later told.

Former police officer Sidney Wink was the man suspected of supplying the weapon that killed Urquhart as well as the weapons used to carry out the Heathrow robbery itself. When detectives visited his Essex home in August 1994 to question him they found him dead. An inquest heard he had committed suicide by shooting himself in the head.

Kenneth Noye figured prominently in the Brink’s-Mat case. He became involved in efforts to smelt the gold and launder it. He killed a detective, John Fordham, who was carrying out surveillance from a covert position inside the garden at Noye’s home in Kent. Noye was acquitted of Fordham’s murder but convicted of laundering the gold, several bars of which were discovered hidden at the house.

Many of Noye’s associates suffered similar fates to John Fordham. One was Kent car dealer Nick Whiting. He vanished, along with a number of vehicles, in June 1990. His corpse was later found on Rainham Marshes, Essex. He had been shot in the head.

Businessman John Marshall was shot dead in his car in 1996. Along with Palmer, Marshall was said to have helped Noye flee the UK after the “road rage” murder of Stephen Cameron, and then been killed to stop police from discovering the link.

Keith Hedley was a Noye associate suspected of helping him escape justice. He was shot dead on his yacht in Corfu in November 1996.

Hatton Garden jeweller Solly Nahome was gunned down on the doorstep of his north London home exactly two years later. Nahome was said to have been involved in the smelting and laundering of the stolen gold. He was a key financial adviser to the feared north London Adams crime family.

Dozens of other victims have been linked to the robbery, some tangential, others less so. Few believe that Palmer’s death will be the last.

Fool's Gold: What happened next

George Francis: murdered in May 2003. Shot dead outside a courier company he ran in Bermondsey, south London. Two men convicted.

Brian Perry: murdered in November 2001. Shot dead outside his minicab firm in Bermondsey. Case unsolved.

Charlie Wilson: murdered in April 1990. The former Great Train robber was shot dead at his home near Marbella.

Nick Whiting: murdered in June 1990. Kent car dealer and associate of Kenny Noye. His corpse was later found on Rainham Marshes, Essex. Case unsolved.

Solly Nahome: shot dead on the doorstep of his north London home in 1998. Said to have been involved in the fencing of the stolen gold.

John Marshall: shot dead in his car in 1996 allegedly to prevent police discovering how Kenny Noye fled the UK after the ‘road rage’ murder of Stephen Cameron.

Keith Hedley: murdered in November 1996. Shot dead on his yacht in Corfu, Greece.

Danny Roff: murdered in March 1997. Shot dead in his car outside his home. Roff was suspected of being implicated in the murder of Charlie Wilson.

Donald Urquhart: the businessman was shot dead in central London in 1993. Reputedly laundered some of the robbery proceeds. A man paid £20,000 for the killing was later jailed.

Sidney Wink: a former police officer suspected of supplying weapons to the Brink’s-Mat team and the weapon that killed Urquhart, he was found dead in 1994. A suicide verdict was given at the inquest.