Britain's most dangerous convicts reveal reality of life in highly restricted 'jails within jails'

One inmate said claustrophobic conditions were like being in a 'submarine'

The grim day-to-day existence of the 60 most-dangerous convicts in the country has been described in unprecedented detail, in a new report on the Prison Service’s highly restricted specialist units.

The little-known units, known as “jails within jails”, house the prison system’s most-notorious inmates. Most were sent to one of England’s five close supervision centres (CSCs) after attacking guards or other convicts.

Once detained in a CSC, they are likely to be held for years in the “most restrictive conditions with limited stimuli and human contact”, according to a new report by HM Chief Inspector of Prisons.

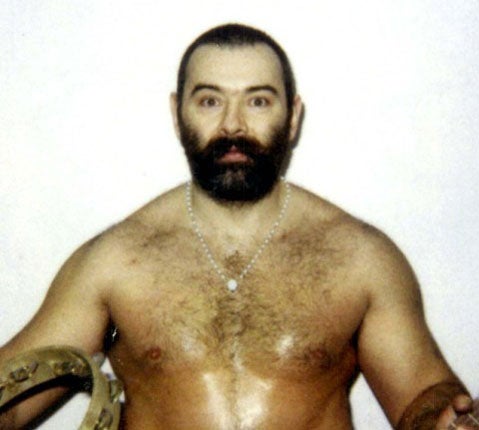

Violent criminals sent to CSCs in recent years include Charles Bronson, dubbed Britain’s most-dangerous prisoner, and the double killer Gary Nelson, who murdered PC Patrick Dunne in 1993.

The inspector’s report shines a rare spotlight on the highly restricted and isolated regimes within the CSCs at Woodhill, Bucks; Manchester; Whitemoor, Cambs; Full Sutton, North Yorks; and Wakefield, West Yorks, with one inmate referring to the claustrophobic conditions as being like a “submarine”.

The report found the exercise yards for inmates were “unacceptably oppressive and dehumanising cages” and the units offered only a filtered view of the outside world and sky. There were too few features designed to make the units feel less austere, said the report.

The inspectors also found that in most units there were too few activities to keep prisoners occupied. At Wakefield, prisoners had only two or three hours out of their cell each day because they were considered too dangerous. Some inmates complained that the short amount of time they had out of their cells could be cut because of staff shortages.

Strict guidelines surround decisions to send prisoners to CSCs but, once inside, inmates are not allowed legal aid to fight the decision under cuts imposed by the Government in 2013. Since 1998, only five inmates have moved out of the system, according to one prisoner in a survey. “When faced with these statistics, I’m left with little hope,” the inmate said. “I feel I’m being warehoused here for a very long time no matter how I behave,” said another prisoner.

The report said no research had been completed into why about a third of the men on the CSCs were black or minority ethnic and 51 per cent of them were Muslim. “The reasons for these large numbers were not understood well enough to ensure processes in place did not discriminate against these groups,” said the report. “We found no evidence of discrimination in the way prisoners were treated on a day-to-day basis.”

Prison authorities do not reveal the identities of those who are held at CSCs but Islamist extremists have been considered for moves if radicalising behaviour is backed up by violence.

Kamel Bourgass, an Algerian jailed for 17 years for involvement in a 2002 ricin terrorist plot and murdering a police officer, was placed in segregation for months because he was “influencing other prisoners” and was considered for removal to a CSC over the assault of another prisoner, court papers show.

A Prison Service spokesperson said: “Selection into a close supervision centre is based purely on the risk the prisoner presents within custody. However, we are examining why there is a higher proportion of black and minority ethnic prisoners in the close supervision centre system.”

Overall, the report found high levels of staffing, control and scrutiny at the units, first set up by the Labour government in 1998, meant that violence was lower than in the rest of the prison estate.

HM Inspector of Prisons Nick Hardwick said: “Leadership of the system was clear, principled and courageous. We do not underestimate the risk the men held in the CSC system pose or the complexity of working with them.”

Michael Spurr, chief executive of the National Offender Management Service, said: “I’m pleased that the Chief Inspector has concluded that the close supervision centres are well-run and I echo his praise for the courage and professionalism of staff.”

Specialist cases: Violent prisoners

Long-term residents of specialist units are men who have carried out terrible crimes and continue with their violence behind the prison walls.

Kevan Thakrar, who is serving a 35-year sentence for a drugs-related triple murder, stabbed three prison officers with a broken bottle at Frankland prison, Durham, in 2010. But he was cleared of all charges for the prison attack after claiming he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of previous prison experiences. He later claimed that he was subjected to “psychological torture” at Woodhill CSC where he was moved from Frankland.

Mark Robinson, a double killer, left five prison warders needing hospital treatment in December 2011 after his bread ration was cut inside the CSC at Wakefield prison. Robinson was serving life for killing a female neighbour and a girlfriend. He had previously attacked guards at other prisons.

Lee Foye, convicted of killing his partner, was sent to one of the secure units after murdering a paedophile in prison. It emerged that the two had taken part in the same group therapy sessions and Foye was heard muttering that the child rapist should be “put down” for his crimes. Foye was subsequently sent to Woodhill close supervision centre in Buckinghamshire where he cut off one of his ears with a razor blade. Three months later, he cut off the other one.